He used to think Jewish athletes were a punchline; now, he wants to help them get a proper paycheck

Jeremy Moses, co-founder of Tribe NIL, believes his new initiative can help Jewish student-athletes finally profit off of their talent

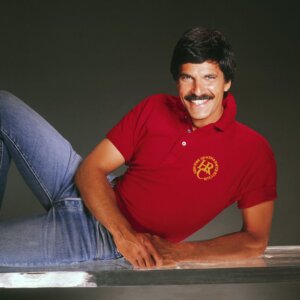

Jake Retzlaff, the BY-Jew Photo by Chris Gardner/Getty Images

My favorite joke in the 1980 comedy Airplane! is, by the standards of a movie featuring a glue-inhaling Lloyd Bridges and an inflatable toy autopilot, one of its subtler gags. A passenger asks a flight attendant for some light reading; in return, she receives a pocket-sized leaflet of “famous Jewish sports legends”.

The vicious canard (just kidding, we’ve been called worse) that the so-called people of the book are ill-at-ease on the court or the gridiron contains a kernel of truth, of course. There’s a reason nearly all Jews know the names Koufax and Spitz — there are few other Jewish sports stars to choose from.

But the rapid growth of the country’s first Jewish NIL initiative, Tribe NIL, would suggest that, in the collegiate ranks at least, such stereotypes are baseless; in barely a year, it has accumulated a roster of nearly 200 athletes.

NIL, which stands for name, image and likeness, allows student-athletes to profit off of their fame and success, most often via endorsement deals requiring commercials, public appearances, paid social media posts and the like. (Here’s Arch Manning, star University of Texas quarterback, flinging a football downfield while wearing *checks notes* Warby Parker glasses.)

Until 2022, however, college athletes were barred from receiving any form of compensation for their services. So NIL initiatives — organizations that help connect students with funding opportunities — are a relatively new phenomenon. Most of the organizations bring together student-athletes with a particular unifying characteristic, usually a connection to a school or region; for instance, the University of Alabama, a college football behemoth, has two NIL initiatives, Yea Alabama and The Tuscaloosa Connection.

But Tribe is unusual in that it is not organized around geography, but around culture.

So co-founders Moses and Eitan Levine lean on a different kind of network: The Jewish professional one. “There are inherent advantages that the Jewish community has,” Moses told me over a Zoom call.

“I always joke that Jewish nepotism is a good thing,” he added.

Virtually none of Tribe’s athletes are able to command lucrative sponsorship deals, which, under the NIL system, are reserved for the very best Division I athletes in the so-called “revenue sports” — football and basketball. A good number of Tribe’s roster, by contrast, are Division III athletes, and few are in football or basketball. They’re still better at their chosen sport than nearly all other human beings, yet not good enough to be recompensed financially.

“That’s a problem,” said Moses. “A D-III field hockey player who doesn’t have inherent NIL value is still working a full-time job. It’s crazy they don’t get any compensation.”

With Tribe, then, Moses imagined other kinds of compensation. “The question we’re asking,” he said, “is how can our athletes use their name, image and likeness to get where they want to be in five or 10 years from now?”

Tribe’s answer is to cultivate closer ties with a myriad of institutions, and with their Jewish stakeholders in particular, in hopes of securing sponsorships, internships and jobs for its growing list of charges.

“Say I’m a big Jewish law firm,” Moses told me, “and I want to show that I support Jewish athletes. What if I hired a bunch of Jewish athletes for my summer internships, and then give them each an extra $1000 to allow us to advertise them on our Instagram?”

Moses and Levine pocket a fee for each deal, on top of whatever the athlete receives. Take the law firm example: In such a scenario, both men would be paid, by the firm, for giving that office access to the athletes — for “making the introductions,” Moses said.

The simple fact these athletes are Jewish is not the sole reason firms would hire them, Moses emphasized. “Like, they have a degree, and a full-time job as a basketball player on top of that, right? They’ve shown a level of commitment.” But Jewishness, Moses believes, can provide the proverbial foot-in-the-door. And he wants Tribe to be the intermediary.

“I wouldn’t ever tell a kid like they should only rely on the Jewish community to network,” he said. “But it’s a silver platter right there for you, and I promise you, it’ll work out for you if you lean in.”

For the tribe, by the tribe

Tribe is the brainchild of comedy writers Jeremy Moses and Eitan Levine. The pair met while working on Amazon’s short-lived sports TV show, “Game Breakers,” where they created a segment called “This Week in Jews.”

The duo, Moses said, quickly bonded over their shared cultural and sporting interests. Moses has a Conservative rabbi for a father and used to work for the site My Jewish Learning. Levine has a sizable social media presence as a comedian, which he often used to highlight Jewish sporting achievements in ways both heartwarming and acerbic.

In 2024, almost by accident, Levine helped broker the most significant Jewish NIL deal yet: A partnership between Manischewitz, of Matzoh fame, and Jake Retzlaff, Jewish quarterback at Brigham Young University. (Retzlaff was dubbed, entirely appropriately, B-Y-Jew.) Levine had worked with Manischewitz on his webseries, When Can We Eat, while Retzlaff had been the subject of one of Levine’s Instagram videos; he played matchmaker and made the shidduch to introduce the brand to the athlete.

Naturally, the photographs of a smiling Retzlaff holding up Manischewitz’s Potato Latke mix did not escape the attention of other Jewish student-athletes. Levine was soon inundated with requests for further kosher NIL deals, Moses told me.

This took both men by surprise; after all, they too had always subscribed to the notion that Jewish athletes were hard to come by.

“Our first thought was, ‘How many Jewish college athletes are there?’” said Moses. He decided to carry out a survey of sorts. “I went on the UCLA Athletics website — because I needed a school with a large population, a large Jewish population, and tons of sports programs — and looked at last names. If I was 75% sure they were Jewish, I counted it.”

His survey was unscientific, to be sure — Moses was a Jewish studies major, not a statistician — but it was effective: He counted 25 names.

“I was like, ‘Wait, that’s just at one school!” he said.

Moses realized that Jewish student athletes, far from being under-represented, were punching above their weight relative to the overall population. Thus was born Tribe NIL.

Schmoozing to success

Tribe’s yichus-heavy approach is premised on what Moses sees as one of American Judaism’s most enduring traditions: Rooting for Jews in sports just because they’re members of the tribe, whether they’re on your favorite team or not.

Moses offered up a choice example about Max Fried, the Yankees’ excellent pitcher. “Maybe you’re not rooting for the Yankees to win, but you’re still proud that the starting pitcher for the other team is a Jew.”

He acknowledged, however, that such an outlook could limit Tribe’s appeal. It would be harder to pull off a paid appearance at a local synagogue, say, or a Q&A with Jewish partners at a business — with a view to potential employment down the road — if the athlete in question doesn’t feel especially Jewish.

So the collective is aimed squarely, and solely, at “proud” Jews, Moses said. “If they’re not comfortable talking about being Jewish out loud, then this is not the organization for them.”

Both Moses and Levine are holding out hope that Tribe will be spared the debates over Israel’s conduct in Gaza, and over competing definitions of antisemitism and Zionism, that have roiled so many Jewish-American institutions. “We really strive to be an apolitical organization,” Moses said. “Because the one time Republicans and Democrats sit together is at a college football game.”

Still, the fairly well-established pathway from U.S. college sports to the Israeli professional ranks is one Moses hopes to exploit, and he’s not afraid of upsetting anyone. “We want to help American Jews play in Israel,” he said. “If this is a political statement, then it’s a political statement. But I don’t think it should be.”