A legendary graphic novelist gets the (bio)graphic novel treatment

Will Eisner, a titan of the graphic novel industry, has never received mainstream recognition. A new biography is hoping to fix that

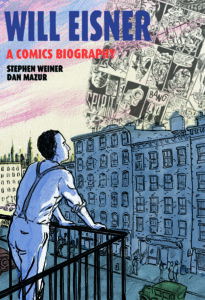

At the drawing board: A young Will Eisner Courtesy of Dan Mazur

In 1992, Art Spiegelman’s Maus won the Pulitzer prize.

The first graphic novel to win the award, Maus testified both to Spiegelman’s singular brilliance and to the graphic novel’s acceptance as a serious medium. This owed a great deal to one man: Will Eisner.

A legendary figure within the comic book and graphic novel industries, yet comparatively lesser-known without, a new biography of Eisner from longtime graphic novelists Steve Weiner and Dan Muzur introduces Eisner to a new generation.

And to do justice to the life and career of the man who coined the term graphic novel, the duo have written — you guessed it — a graphic novel, entitled Will Eisner: A Comics Biography.

“What, it should be an opera?” Mazur joked, when I met him and Weiner over Zoom. “If you want to learn about Will Eisner, and you don’t want to read a graphic novel, I don’t know how that works.”

Mazur and Weiner had moved in the same comics circles in Cambridge, MA, for several years. Their work had even appeared side by side in 2017’s Cambridge Companion to the Graphic Novel. But they officially met only in 2022, when Weiner pitched Mazur a graphic novel about Eisner-the-artist and Eisner-the-man.

The pair clicked immediately. “We just started talking about the books and comics we liked,” said Weiner, who has a shock of curly white hair. “I thought: This is going to work.”

Mazur, an expert on early comic history, was especially taken by the idea of illustrating Eisner’s “grubby, romantic career beginnings.” What’s more, he and Weiner both felt Eisner’s early career had never been properly examined.

“We wanted to think about what the challenges really were for him in this industry that wasn’t yet an industry,” Weiner told me.

Striking out on his own

The biography’s first section takes the reader from Eisner’s upbringing in 1920s Jewish Brooklyn to the still-fledgling world of comics in the 1930s. Mazur’s drawings are effective at capturing the poverty of Depression-era New York, while Weiner, who wrote the narrative, details the considerable drive Eisner needed to pull himself up.

Interestingly, though the biography is about Eisner’s work, we don’t see examples of his drawings; the duo are less concerned with the specifics of Eisner’s art than with the life that made it possible and the stories he told.

During the first half of the 1930s, Eisner eked out a living as a writer-cartoonist for the New York Journal-American, a now-defunct New York City daily that was the first American newspaper to publish a daily comic strip. He also found work as a freelance illustrator for various pulp magazines. One such publication was the short-lived Wow!, which lasted just four issues, but whose editor — Jerry Iger, now perhaps overshadowed in popular memory by his grand-nephew Bob, CEO of the Disney corporation — took a particular liking to Eisner’s work.

The two formed Eisner & Iger in 1936, which established itself as the most important comic book packager of its time. Several artists who would eventually rank among America’s most influential passed through the business’ one-room office on East 41st Street — including, most notably, Jack Kirby (Jacob Kurtzberg, by birth), who went on to create many of the Marvel Comics characters that are today Hollywood staples.

Eisner, though, sold his share of the firm to Iger in 1939, having signed an agreement with a Sunday newspaper to draw comics. The Spirit, an Eisner character that first appeared in the Des Moises Register in June 1940, would morph into a regular 16-page Sunday comic strip supplement known colloquially as “The Spirit Section.” At its height, it featured in 20 Sunday newspapers and had a circulation of more than five million copies.

The Spirit was the first truly highbrow comic strip, and Eisner’s most enduring creation. (“It made a big impact on me,” said Mazur.) The domino mask-wearing private investigator possessed no superpowers, relying on his wit and physical prowess alone. In many ways, he was a vehicle for Eisner to experiment with genre and tone, exploring the kind of thorny moral terrain that conventional superhero comics wouldn’t even gesture at.

P’Gell of Paris, for example, a supporting character in The Spirit Section, was a none-too-subtle allusion to the Parisian district of Pigalle, which, during World War II was a red light district popular among U.S. servicemen. Her dark, seductive demeanor was Eisner’s tribute to the femme fatales of the noir films that dominated 1950s cinema, while her success in getting under the Spirit’s skin — Eisner’s protagonist was usually unflappable — upended the gender dynamics of 1950s superhero comics.

In time, The Spirit would provide a blueprint of sorts for a later generation of graphic novelists. In its depth and ambition, however, it was wholly out of step with the so-called Marvel Boom of the 1950s and ‘60s.

“He was too far ahead of his time,” Mazur said. “That’s why he left.”

The graphic novel arrives

After the United States entered WWII in 1941, Eisner spent four years in the Pentagon designing instructional comics for military magazines. He enjoyed the relative dependability of the work, Mazur told me. He had also grown tired of the homogeneity of superhero comics, so what began as a wartime position grew into a peacetime business.

For the better part of three decades, Eisner supplied the military and other companies with educational comics. His most frequent publication was Preventive Maintenance Monthly, which colorfully detailed ways to guard against equipment mishaps. (Its protagonist was G.I. Joe Dope, a chronically wayward infantryman.)

Two things revived Eisner’s interest in the comics industry. First, the emergence of a new, and decidedly Eisner-esque, approach to comics. Eisner attended various comics conventions in the early 1970s, where he was surprised by the variety of offerings and, on occasion, feted as a returning hero.

“Guys in their 20s were running up to him, saying, ‘Oh, Will Eisner! The Spirit is so great!’” Mazur said. “For a guy who’d always wanted to be creative, what was happening then was just too appealing to not want to be part of.”

The second was less heartening: The death of Eisner’s 16-year-old daughter Alice, from leukemia, in 1970.

The result was Eisner’s profoundly personal 1978 book, A Contract with God: and Other Tenement Stories, about life in an impoverished Jewish tenement in New York City; the titular story described a religious man giving up his faith after his young daughter dies.

Eisner presented Contract with God to publishers as a “graphic novel,” the first known use of the term. Though comics had already outgrown their superhero origins, Eisner wanted to make this difference obvious for audiences.

Contract with God ushered in the era of the graphic novel as a longer, more literary endeavor, distinct from comics; Eisner would write no fewer than 20 over the next 30 years. Many explored Jewish themes — Fagin the Jew, expanding the backstory of the Charles Dickens character, is an obvious example — while others were artistic takes on classic novels like Moby Dick.

Though Mazur’s more expressive drawing style is nothing like the rigid, straight-edged approach Eisner favored, it is nonetheless superb at conveying Eisner’s evolution. The result is warm and inviting, or, as one reviewer put it, a haimish biography, a term Eisner would have doubtless recognised.

It’s a worthy tribute to a man who, first with The Spirit, and later with Contract with God, laid the foundation for Spiegelman’s Pulitzer win.

“Eisner saw what no one else saw,” Weiner said. “He saw that there was no limit to how this form could be used,” Mazur added.