Created in hiding during WWII, a Jewish artist’s underground ’zines are finally rising to the surface

From 1943 to 1945, Curt Bloch produced 96 editions of a satirical publication he called ‘The Underwater Cabaret’

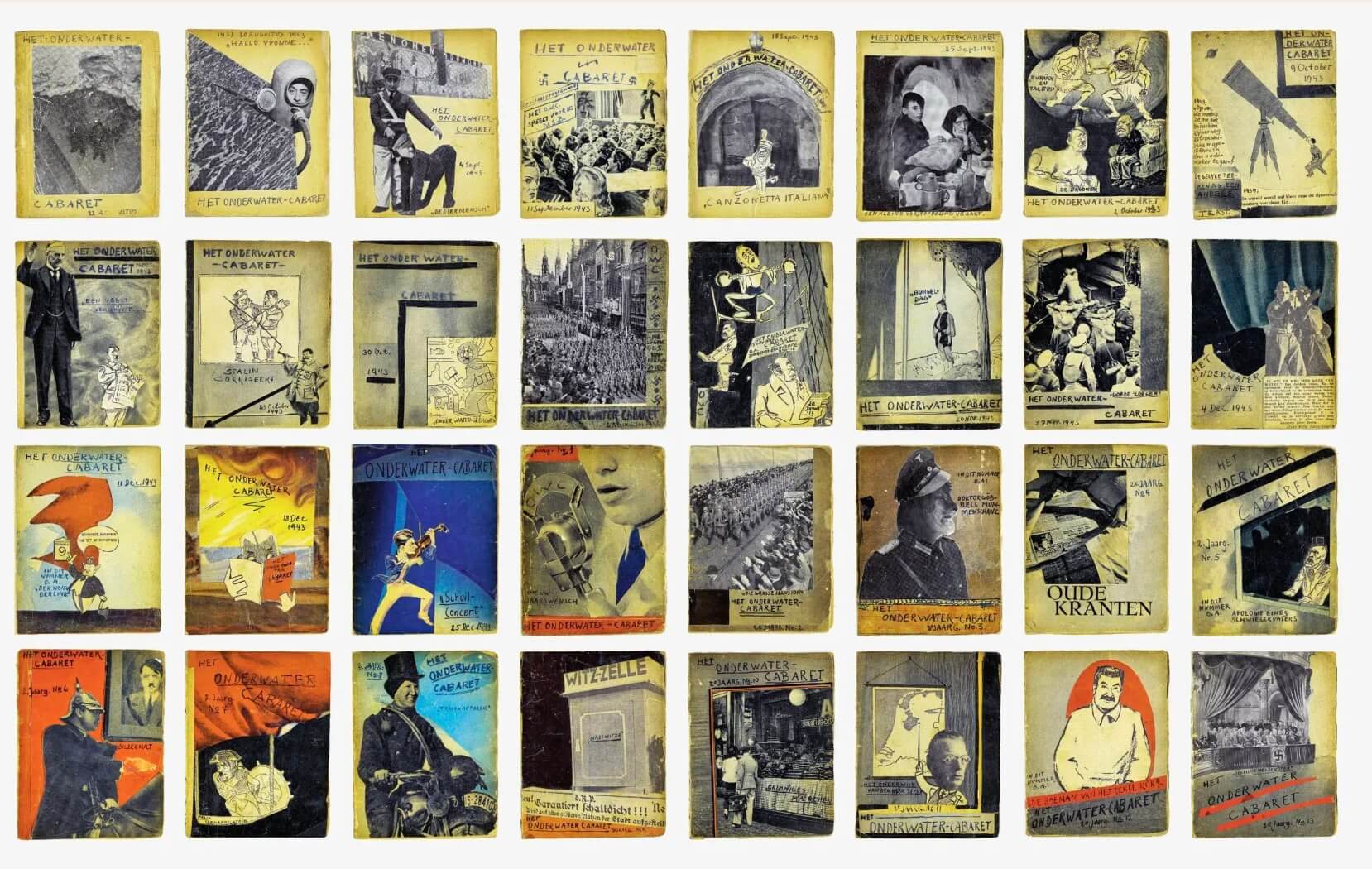

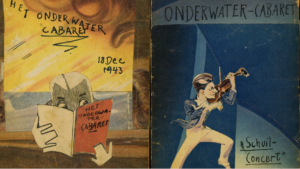

Covers of the first 32 editions of ‘The Underwater Cabaret,’ an underground proto-zine produced by Curt Bloch in an attic crawl space in Enschede, Holland, from August, 1943 to April, 1945. Courtesy of Stiftung Jüdisches Museum Berlin/Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection

What do you do when you finally admit to yourself that you’ve had something akin to Anne Frank’s diary in your living room for your entire life?

Simone Bloch mostly ignored it. The four bound volumes were like all the other antiques in the Queens home furnished by her parents, who traveled to Europe on buying trips for their Midtown store, Continental Antiques — nothing to see there. Occasionally, her father pulled one of the old-timey looking books down from a shelf and read a poem aloud. In German. WTF?

Here’s WTF: Simone’s father, Curt Bloch, a wicked satirist, wrote those poems. He also wrote songs and essays and wartime updates. Hundreds of them. He made collages of Nazis — Hitler, Göring, Goebbels, all the biggies — depicting them as babies, animals, buffoons. He somehow managed to corral all of this into 96 postcard-sized magazines while hiding from the Germans and their Dutch collaborators in an attic crawl space in Enschede, Holland, from August, 1943 to April, 1945. He produced them at a pace of one per week.

To be clear: Curt didn’t print his magazines; how could he? There was, and still is, a single copy of each which circulated among 30 or so of the Jews hiding in Enschede. Het Onderwater Cabaret, or The Underwater Cabaret, was Curt’s answer to the untenable situation he, his family, and the rest of Europe’s Jews had found themselves in. The title is a play on the Dutch expression for hidden Jews: “Onderduikers.”

Divers.

I: Going Down

In 1933, Curt Bloch was in his early 20s and living in his native city of Dortmund. He was a Jewish lawyer with a promising career in the judiciary when the Reich decreed that no Jew could hold a position in the civil service, and he was forced to resign. A non-Jewish co-worker sent a gang of Nazis to beat him up, and soon after, as more Nazis were knocking at his door, he escaped out of an attic window, crossed the German border, and rode into the Netherlands on a bicycle.

Curt stopped first in the Hague and then settled in Amsterdam, working odd jobs, including selling carpets and antiques. He slipped back into Germany just once, to submit a death certificate for his father, a veteran who’d fought for Germany in World War I. In May 1940, the German Wehrmacht invaded the Netherlands, and the disenfranchisement of Jews proceeded much as it had in Germany. Dutch Jews carried ID cards stamped with J, were forbidden from holding civil service jobs, and were barred from schools, universities and public facilities. By May 1942, they were forced to sign over their assets to the Reich, affix yellow stars to their clothes, and were now eligible for “resettlement,” a process that began in a crammed cattle car and ended in a concentration camp in Poland. Curt went into hiding.

II. Dry Land

Simone Bloch is a therapist and sometime playwright who lives in a brownstone on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Her mother, Ruth, a survivor of several camps, is 100 years old and lives in her own apartment on the ground floor. Simone shares the rest of her house intermittently with her three children and four grandchildren, an ever-changing number of dogs, plus the occasional traveler. Currently, her elder daughter, Hannah, a lawyer like her grandfather, is ensconced with her husband, children and dog while she teaches law at a local university.

I know all this because Simone is a friend. We met in Central Park when my dog, Otis, was a puppy, and her dog, Manny, still roamed the earth. Since then, we have been two-thirds of a weekly writing group . Even when we don’t have any writing to discuss, we meet and talk, and Simone, in her therapist’s guise, comes in particularly handy. Over the past 11 years, we have watched Simone, now in her mid-60s, midwife her father’s work, which miraculously survived the journey from Enschede to Manhattan, back out into the world.

What took so long?

Simone had to do all the other life things before she did this. And, as she puts it, it wasn’t so appealing to have this story. Really, nobody wants to hear it. But Simone never had the luxury of not knowing about death. Other people had grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins. What is a grandmother? young Simone wanted to know. Where was hers? Her parents told her. After that, she assumed everyone else must know about death, too. There were a few kids in high school whose parents had survived the Holocaust, but talking about it wasn’t a thing back then.

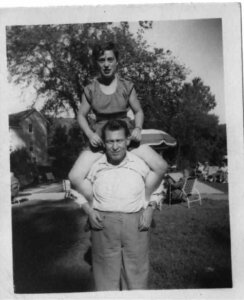

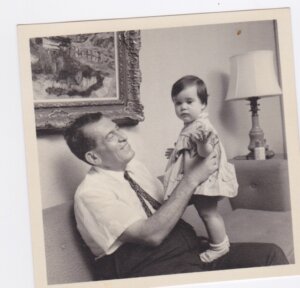

As if that wasn’t enough, when Simone was 10, her 22 year-old brother, Stephen, died by suicide. He was born in Amsterdam and made the journey to New York with parents when he was just one. It was the 1950s, a time of conformity, and his German-speaking, Holocaust-surviving parents distinctly did not conform. The transmission of trauma is real, says Simone. Being the child of survivors had a profound effect on her brother’s emotional health. Simone, herself, was a quiet child who cried easily, but as she became more aware of her parents’ past and processed her brother’s death, she was determined to be the tough one, the one who got her shit together. Then, when she was 15, Curt died.

Simone had had a difficult relationship with her father. She was a wild teenager who didn’t consider her own trauma until quite recently, having spent the better part of her life diminishing the sadness to herself, to other people, and eventually, to her children. She acknowledges the fury she felt towards her father when he tried to rein her in, though she didn’t realize what brand of dangerous behavior Curt imagined she might be engaged in until she was in her 50s and saw the German television series Babylon Berlin.

Curt tried to keep Simone safe because he could not do that for his sisters. Erna, the elder, was deported with her husband, Max, and both were murdered in the camps. Curt’s younger sister, Leni, along with their mother, had followed Curt to the Netherlands and gone into hiding separately from him. The two women were discovered and deported. They were murdered at Sobibor. Leni was just 19.

Simone used our writing group sessions as a kind of psychoanalysis. Curt became a character she had to contend with. Like her father, Simone is both furious and funny, and Curt’s gift for satire — that particular admixture of anger, fear and humor that is a common Jewish coping mechanism — has been his legacy to her. For Simone, it is her defense against the world, most particularly from ending up like her brother.

III: Surfacing

Simone’s daughter Lucy became interested in The Underwater Cabaret when she was an undergraduate at Grinnell studying history and German. She asked Simone what the little magazines were, exactly. Simone replied: “Your grandfather made them while he was in hiding.” Did other families have something like them? Lucy wanted to know. (“As though everyone in hiding was doing craft projects,” Simone told me over the phone.) Simone said no. Lucy got a grant to go to Germany and see if there were non-Jewish equivalents to Het OWC, as Curt sometimes called it. There were not. But her advisors, along with the German Academic Exchange Service, found the magazines compelling. Simone thought, Huh.

This was the beginning of The Underwater Cabaret’s journey back to the surface. It went in stages. First, Simone and Lucy, who was also an artist, considered co-authoring a graphic novel of Curt’s life. After a bit of work they abandoned that idea, because, well, the writing and art for the work already existed. Simone then started speaking to friends, to academics, and to publishers with whom she was acquainted about how to get the story out. She has a gift for emailing and calling people she barely knows and asking for their assistance. There were emails back and forth with a Dutch publisher and two years talking to an art historian.

After hundreds of calls and emails, she met Thilo von Debschitz in a Facebook group called Jews Engaged Worldwide in Social Networking. It has the unlikely nickname of “Jekke,” a word coined by Israelis referring to German-born Jews who’d made aliyah. Thilo is not Jewish, nor does he live in Israel. He is a graphic designer in Wiesbaden whose grandfathers were Nazis. His maternal grandfather died by suicide when he learned Hitler was dead. Thilo has an interest in bringing lost stuff to light, particularly Jewish stuff, so together he and Simone re-approached the Jewish Museum Berlin, where, 10 years earlier, she had pitched The Underwater Cabaret.

IV: Up for Air

Finally, in February of 2024, after a nearly 13-year journey, the JMB presented an exhibit of The Underwater Cabaret and made it part of their permanent collection. I traveled to Germany for the first time to attend the opening, and despite a deep knowledge of Curt’s story, I was alternately heartbroken and astonished.

The evening began with a presentation in a large atrium, packed with people, where the museum director, the curator, and Simone spoke. An actor performed a poem in the original German to great effect; the irony in his tone as he landed on the tight rhymes brought Curt’s writing to life. A young woman played and sang pieces Curt called songs in the magazines, accompanying herself on the piano with music she had composed for the occasion.

The audience then moved on to the exhibit, where the magazines were placed in a chronological timeline of history and of Curt’s life. There were also copies of the original magazines from which Curt had taken clippings for his collages and a decades-old video recorded by the Shoah Foundation of Karola Wolf, a woman who had been in hiding with Curt and with whom he had fallen in love.

Later that night, there was a private party for family and friends. They had come from all over to mark Curt Bloch’s life and to celebrate Simone, who, in her way, has come up for air, as well. She feels an enormous sense of pride in the response to her father’s work.The journey isn’t over — the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam is mounting an exhibit next winter and surely there will be others — but there is a lightness to her, because she has both accomplished a great task and relieved herself of a great burden.

I have thought a lot about what Curt’s work might have meant to his fellow “divers.” I imagine that waiting for The Underwater Cabaret each week helped them mark the time and reading it made them laugh in the face of gut-churning terror. Passing it along to each other, despite the grave danger of doing so, gave them the courage to persevere. Maybe even to hope. Het Onderwater Cabaret was a social media platform of its time, creating community, spreading the truth, using visuals to depict the indescribable, and channeling fear into action. At a time when one in five Americans do not believe the Holocaust happened at all, a new generation of divers is hiding in cities across the country, communicating with each other on smart phones, and depending on their neighbors for support. The reemergence of Curt Bloch could not be more apt and unsettling.

A coda: Curt made many trips back to Germany as part of his work as an antiques dealer. In 1972 he returned to Dortmund to attend his 45th high school reunion. There he was hailed by old friends, many of them former Nazis. One greeted him like this: “Curt, we weren’t expecting you.”