A Cantor’s Tale

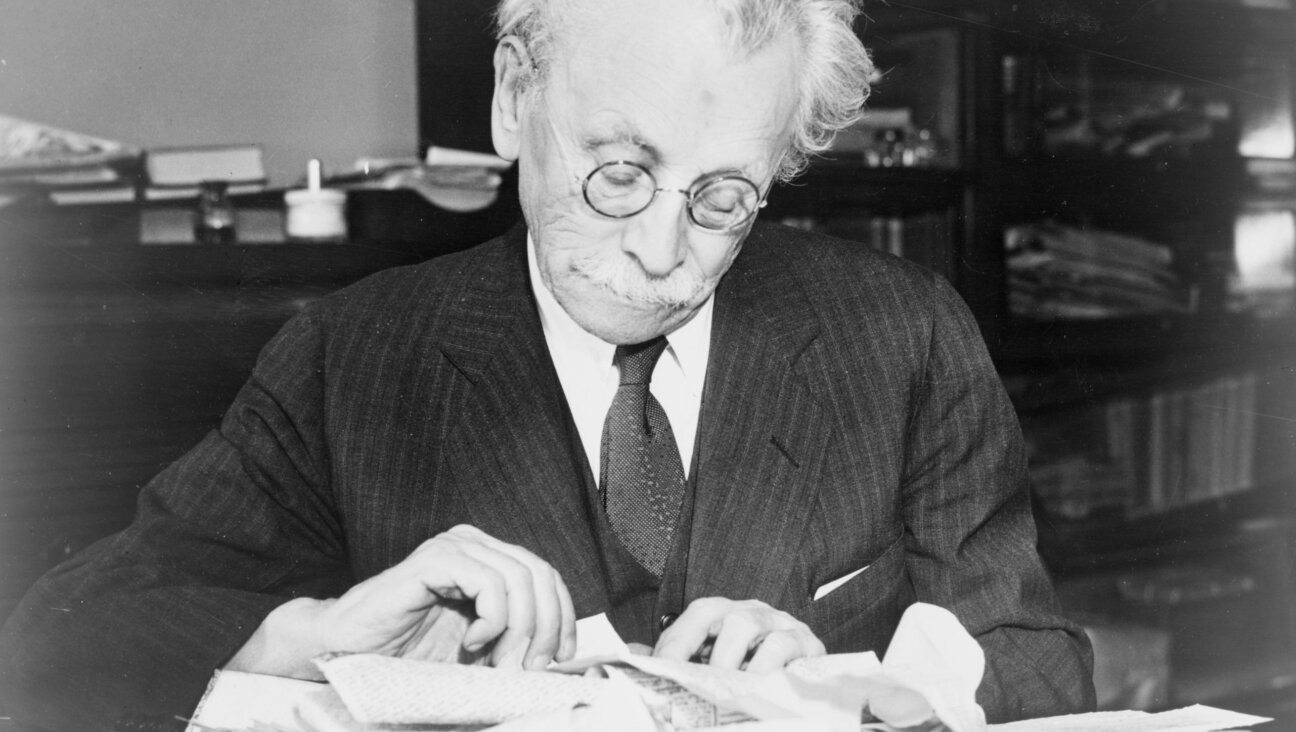

He was a vaudeville star who was offered $100,000 to appear in Al Jolson’s “The Jazz Singer.” He toured North America, Europe and Palestine to tremendous acclaim, earning record fees and a kiss from Enrico Caruso. When he died in 1933, at the age of 51, more than 5,000 people attended his funeral in Israel, and more than 2,500 came to his memorial service in New York City’s Carnegie Hall.

Not bad for a cantor who was born in a Ukrainian shtetl. Yet at the time of his death, Cantor Josef “Yossele” Rosenblatt was almost penniless, saddled with debt from a disastrous business investment that had bankrupted him in 1925. And while he left behind a series of legendary recordings and a reputation as one of the finest cantors of the past century, a large chunk of his legacy was nearly consigned to the trash heap. Literally.

Last summer, Todd Rosenthal, one of Rosenblatt’s great-grandchildren, discovered three previously unknown books containing a number of Rosenblatt’s own compositions, many in his own handwriting, along with arrangements of works by other prominent Eastern European cantors.

Rosenthal’s grandmother, Sylvia, had recently passed away, and the family was preparing to sell the condominium she had once shared in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., with her husband, Marcus, one of Rosenblatt’s younger sons. (Marcus died in 1991.) Rosenthal, who runs a tutoring company in Florida’s Port St. Lucie and describes himself as a life-long collector of “odd items,” noticed some prayer books lying in a trash bag filled with his grandmother’s effects. He decided to see what other mementos might have been thrown away. After combing through no fewer than 20 Hefty bags stuffed with his grandmother’s belongings, Rosenthal surfaced with three books about his great-grandfather’s music. While he’s not sure how his grandmother came by them, Rosenthal speculates that his grandfather may have found them in his own mother’s home in New York City in the late 1960s.

“My grandfather probably took these books as a memento of his father, and never mentioned them to anybody in the family,” Rosenthal told the Forward in a recent interview. “They just sat in a spare drawer in one of his rooms.”

Initially, Rosenthal himself wasn’t exactly sure what to make of his find. When he noticed a stamp that read “Componirt von J. Rosenblatt Obercantor Hamburg,” however, he began to feel chills; Rosenblatt had been chief cantor of a Hamburg synagogue from 1906 until 1911, when he immigrated to America. The books also bear handwritten notes alluding to positions that Rosenblatt held in Hungary during the late 1890s and early 1900s.

The earliest of the books appears to be entirely in Rosenblatt’s own handwriting, and according to Rosenthal, the dates on some of the compositions indicate that Rosenblatt produced them when he was only 14 or 15 years old, several years before he became a professional cantor. (Though Rosenblatt had been a child prodigy, custom dictated that he could not turn pro until he had reached the age of 18 and had married.) The second and third volumes were prepared in the elegant hand of a professional music copyist, but Rosenblatt’s handwritten notes and doodles are scattered throughout the margins. Together, the three books include more than 2,000 pages of material dating from the early 1890s to 1911, and ranging from solo cantorial pieces to choral works and songs for the holidays and the Sabbath. The books even include what appears to be an orchestral piece by the cantor.

“I’m not musically inclined, and I’m not really involved in the temple. And as a former journalist, I have a certain skepticism about things,” Rosenthal said. “But when I opened those books, I got excited.” Still, Rosenthal needed help determining the provenance and nature of the material he had stumbled across. In search of experts who might be able to assist him, he came across an article about Cantor Rosenblatt that had been penned by David Olivestone, a self-described “collector of Rosenblatt ephemera” who has contributed biographies of several cantors to the Encyclopaedia Judaica. (Olivestone is director of communications and marketing at the Orthodox Union, and edits the prayer book “The NCSY Bencher.”)

To examine the books firsthand, Olivestone traveled to Florida. He was in the company of Cantor Yaakov Motzen, who serves as musical director of Cantors World, an organization dedicated to reviving interest in cantorial music. Together, Olivestone and Motzen spent two hours poring over the Rosenblatt materials. “Any time you get to touch something by a personality as large as Yossele Rosenblatt, it’s a thrill,” Olivestone said in an interview. “It’s also a thrill because it was unknown to the public for 70 years.” According to both Rosenthal and Olivestone, it was Motzen who identified a number of pieces by such other prominent Eastern European cantors as Zeidl Rovner and Pinchas Minkowski.

While Olivestone feels that the true significance of the materials will not be known until they are deposited in an institution where scholars of chazzanut can examine them more fully, Rosenthal has not yet decided what to do with his great-grandfather’s books. He would, however, like to share them with the broader community; and it’s clear that the discovery has already affected his relationship with a grandparent who died 30 years before he himself was born. “It gave me an appreciation for my great-grandfather as an artist, and as someone who had a passion for something,” Rosenthal said. “To actually see this work at close range, and to touch it, gave me a feeling of pride that I couldn’t have imagined.”

Next week: The unlikely crowd behind today’s startling revival in cantorial music.

Alexander Gelfand is a writer living in New York City.