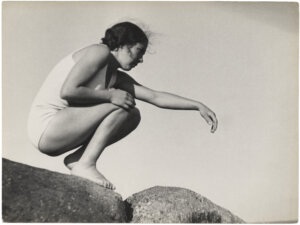

He photographed athletes and he photographed nudes — André Steiner contained multitudes

Just in time for the Olympics, Paris is celebrating the work of Jewish photographer André Steiner

‘Goalkeeper’ (Rudolf Hiden), 1936. Courtesy of © Nicole Steiner-Bajolet © Martine Husson

The Paris Olympics begin next month, and the City of Light’s Museum of the Art and History of Judaism is celebrating with an exhibition on a Hungarian-born French Jewish photographer, an accomplished athlete himself who served in the Resistance in World War II and who focused on creating images of sports, nudes and the human body in motion.

The photographer is André (born Andras) Steiner, the exhibition is titled “The Body: From Desire to Transcendence,” and the museum is in the Marais, Paris’ historically Jewish neighborhood.

“Steiner was one of the first in 1924 to experiment with the first Leica camera,” François Cheval, the exhibition’s curator, said on Zoom from Paris. “He had great success” with French magazines in the 1930s, notably with sports photography. He specialized in the beauty of the moving body, the free gesture, and the beauty of the nude figure.

Steiner was born in Hungary in 1901. He became a committed Communist — he was involved with the Socialist Federative Republic of the Councils government, which lasted in Hungary for less than a year in 1919. He left for Vienna, where he studied sound engineering, also taking photography lessons, and worked as an engineer. He received the Leica while a student at Vienna’s Technische Universität.

A sports aficionado, he was a swimming coach at Hakoah Vienna, a sports club for Jews, Cheval said. (“Hakoah” means strength in Hebrew.) Because of antisemitism in Vienna, “Jews had no possibility to enter themselves in normal club sports,” Cheval said. Steiner met Léa (later Lily) Sasson when she was 13; later she became his wife. She was descended from a Constantinople Jewish family. He made a series of nude photos of her.

As antisemitism grew even worse in Vienna, they moved to Paris, where in 1928 he won the decathlon event at the World University Games. He worked as a sound engineer on movies, Cheval said, before deciding to devote himself to photography, studying the French avant-garde and becoming part of the “New Vision” school of photography, which aimed to make the camera a reflection of daily life. “He considered the photographed body a manifesto for both individual and social emancipation,” the museum’s commentary on the exhibition states.

His political leanings influenced his art. For Steiner, “the people who have the power, the bourgeoisie, are fat,” Cheval noted. “The revolutionary always has a perfect body. For preparing the revolution, you must have the perfect body.”

When World War II began, he became an aviator in the French military. After the French were defeated, he moved to Cannes, in the south of France, and joined the Resistance. “Steiner was a German name, but he said in the newspaper he was born in France, in Alsace,” near Germany, Cheval said, “and he was never suspected to be a Jew.” Steiner used his photographic skills in the Resistance, taking pictures of coastal fortifications.

After the war he resumed photographing, concentrating on science and technology, in Paris, where he died in 1978.

“He stayed a ,Communist, he never changed,” Cheval said, “even in the 1960s and 70s. All his life he considered Communism is the only way possible for humanity.”

The exhibition runs through Sept. 22.