Even in a time of grief and anguish, the show and the art must go on

‘Seeking Joy’ was originally conceived as a light, celebratory exhibit — after Oct. 7, 2023, everything changed

One of a series of interconnecting photographs shot by Debbie Teicholz Guedalia, six months after Oct. 7. Photo by Debbie Teicholz Guedalia

When curator Phyllis Freedman was thinking about the Dr. Bernard Heller Museum’s next exhibition she wanted it to stand in stark contrast “One Nation,” a 2023 exhibit that explored immigration, diversity and plurality in America.

“It was very well received, but now it was time to do something lighter,” she told me as she sat in her office at Hebrew Union College (HUC) on 4th Street. “We’ve done exhibits about homelessness and climate change. Now we wanted to do something that was fun.”

The theme would be joy and the exhibit was dubbed “Celebrations.” Invitations to submit work were emailed to more than 500 artists of diverse cultural, geographic and religious backgrounds.

Then came Oct. 7, 2023, and, for a time,Freedman debated whether they should proceed with the exhibition at all. In the end, the team decided it was never more timely.

“Despite the horrendous state of the world, people still hoped and aspired to joy,” said museum director Jean Bloch Rosensaft who joined our conversation.“And we as Jews always choose life. Even during COVID, marriages took place, maybe not in big halls, but for smaller groups in backyards. There were Bar and Bat Mitzvahs on Zoom. We still celebrated. Of course we knew we had to change the title of the exhibit. ‘Celebrations’ was not appropriate. But ‘Seeking Joy’ is.”

The 50 eclectic works that were selected from 150 submissions depict celebrations of all kinds and, each expresses hope for the future in its own unique way. Some also hint at pain, loss, and grief.

There are paintings and photographs and digital prints and sculptures and works made of found objects and combinations thereof. Some are very small, others large; some realistic, others abstract.

While many are Jewish-themed, others are secular, a few are arguably political. It is an extraordinarily complex exhibit, and made all the more striking in the soaring, expansive, very white, and brightly lit ground floor gallery at HUC.

“Our criterion for selecting work is its quality,” said Freedman. “Is this a good work of art? That’s the first and major criterion.”

“When we do an exhibit we look at it through a Jewish lens,” Rosensaft said. “What do Jewish texts and history teach us about this subject? But we also want to show how the subject has universal meaning. As a Jewish institution we want to foster understanding across differences that are dividing our society. We want to make sure we present the experiences of other faiths and ethnicity. The joy of the show is that as you go from piece to piece you experience surprise and recognition. Surprise because each piece looks and feels so different from the ones next to it and at the same time you recognize each experience and can relate to it.”

The pieces are grouped thematically. One wall features weddings; another is all about holidays, still another presents mundane pleasures. One photograph, “Purim Parade in Israel,” by Bonnie Astor, displays a garishly costumed female clown on stilts. Composed of appliqued, quilted and embroidered cotton, Anita Rabinoff-Goldman’s “The Tiles that Bind” depict four comically conceived women, playing Mahjong, their longstanding ritual speaking to mutual connection. On a more nostalgic note, “Ice Cream Memory,” an oil painting by Tanya Lavina, portrays the artist’s remembrance of her late father and sister sharing an ice cream.

None of this is to suggest that the events of Oct. 7 have been forgotten. Freedman and Rosensaft are keenly aware that for most Jews, and others across the globe, the tragedy of that date and the horrors that followed represented a defining turning point.

Yet only one piece, consisting of five interconnecting photographs by Debbie Teicholz Guedalia, zeros in on that topic. Shot six months after Oct 7, they feature, among other scenes, the communal burial ground at the Nova Music Festival site and the bullet-ravaged home of a murdered resident of a kibbutz on the Gaza border. The final picture in the series is a photograph of an art installation at Hostage Square. This surreal work shows a group of chairs, each adorned with the eyes of the hostages staring out at the viewer. The word “Hope” is boldly painted in large block white letters onto a graffiti covered back wall.

Rosensaft came across the piece on Instagram and knew she wanted to include Guedalia’s work in the show.

“We needed to show that even though we are celebrating there is terror and war,” said Rosensaft. “And it’s placed in such a way that wherever you are standing in the gallery space when you look back you see it. But in the end, what does the piece say? It says ‘Hope.’”

Rosensaft is mindful that there is great suffering in Gaza as well. “We bleed for everyone,” she said. “But we are people, not generals and this is not a political exhibition.”

Most of the contributions were created prior to Oct. 7. But only one artist, Jeffrey Schrier, reworked his piece, “Joy Not Babel,” to suggest his current mood in the aftermath of that fateful day. He burnt and tore the edges around its border.

“Thoughts and feelings of fragmentation and brokenness provided the concept for the framing mat,” Schrier wrote to me in an email. “I ripped and set on fire leftover unused prints from the edition master to create a mat border, also to reference our custom of tearing a ribbon as an expression of loss.”

Still, the word “joy” is prominent in the title and forms the aesthetic centerpiece in Schrier’s colorful abstraction. It’s written in four languages — Amharic, Arabic, Hebrew and Tibetan — that emerge from cultures that share a commonality of struggle and conflict.

For both Rosensaft and Freedman, “The Wedding” by Naomi Grossman is a high point of the exhibition. It’s a delicate and skillfully wrought wire sculpture featuring two intertwined female forms. The wires are at various points sculpted to create words of happiness and unity — “to have and to hold,” “enjoy,” “in laughter,” “in sorrow.” While not readily legible either in the sculpture itself or as projections on the back wall they are nonetheless lyrical and haunting as designs and shadows. You have to come up close to see what the words say, indeed that they’re words at all.

“I work with wire because it’s both strong and fragile like women and marriages. All marriages are strong and fragile, not just gay marriages,” Grossman told me over the phone. “I also love to see how people respond to my work, depending on where they’re standing in the gallery. If they’re at a distance, they may say, ‘They let her draw on the walls.’”

Grossman said she viewed the work as political, especially in this fragile political environment. “Almost everyone knows someone or has a family member who is gay,” she said. “My daughter has a wife. I have nieces and nephews who are gay. Their weddings are like any other weddings. We embrace it all. It’s just love.”

Two works that I found especially intriguing are made up of found pieces. In John Lawson’s “Street Songs — Constellation,” the backdrop is composed of beads that he picked up off the street the morning following Mardi Gras. A trumpet, another found object, is mounted on top of the beaded configuration. The assemblage captures the joy of music and song.

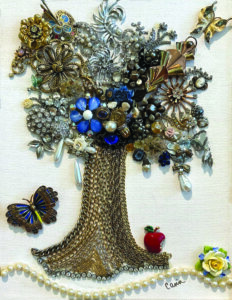

Likewise, in Carin Greenspan’s “Treasured Gems,” a jewelry mosaic, the artist has used her late mother’s costume jewelry to create a “Tree of Life” composition as a tribute to their loving relationship and the happy memories that the mostly glass brooches, earrings and necklaces inspire.

“One day I was looking through my mother’s bags of costume jewelry and realized how meaningful these pieces were to me,” Greenspan told me. “So I started creating the work during COVID, in large part to occupy my time. My father’s cufflinks and tie stud also ended up in the piece.”

For me, the one piece that encapsulates the spirit of the exhibit is Holly Berger Markhoff’s “Silent Celebration,” an unsettling work, featuring three women standing alongside each other facing the viewer. Each sports a child-like party hat placed on their heads at a jaunty angle while their expressions evoke a deep, private pain. We don’t know why the women are distressed, just that they are. Stylistically the painting brings to mind Modigliani and embraces contradictions.

“These are strong, sensitive modern women,” Markhoff told me. “They’re leaders and they know they need to put on those party hats. They’re not faking joy, but rather pushing themselves to be happy through their sadness if it brings joy to others. As Jews it’s our choice and responsibility to make joyful events as an expression of resilience. We don’t always feel like doing it, but we get up and do it anyway because it’s a mitzvah.”

The recent opening of “Seeking Joy” attracted a large diverse crowd, including artists and academics and various school administrators and officials, “who did not want to leave,” said Rosensaft. “The art really touched people’s souls.”

“Even after a terrible year we have to be strong and joy is one of the best ways to be strong, to give hope for a better future,” Yael Hashavit, Consul for Cultural Affairs in North America for the State of Israel, who attended the exhibit, told me over the phone. “The variety, the different aspects of art — each piece brings another angle. There are many ideas represented here and I’m proud of the artistic choices that were made. I think about this exhibit all the time.”

“Seeking Joy” will run through June at Hebrew Union College — Jewish Institute of Religion.