Hidden in plain sight, a Holocaust memorial takes on new significance

New York artist Harriet Feigenbaum, 85, says her work is more relevant than ever

The memorial, located at 27 Madison Avenue, was created in 1990 by Harriet Feigenbaum. Photo by Mia Faye Kreindler

Even though it stands 38-feet tall, the Holocaust Memorial outside Madison Square Park is easy to miss. I live near Madison Square Park, but I didn’t notice until one day when I was walking and the silver plaque next to the memorial was glistening in the sun.

Carved into a column on the Appellate Division Courthouse of the New York State at 27 Madison Avenue, the memorial was created in 1990 by Harriet Feigenbaum.

Feigenbaum, a Jewish New York City native born in Brooklyn in 1939, is known for her outdoor sculptures and art installations. She has lived and worked for more than 20 years in a spacious Flatiron District loft. When you walk into her studio, which is filled with books, paintings and art supplies and illuminated by enormous skylights flanked by dark wood beams, it feels like entering a portal into a New York that no longer exists.

“This is a memorial to everybody,” Feigenbaum, 85, told me while sitting in an armchair across from me in her New York City studio, “but I wanted to get in the fact that the Jews were the focus of the Holocaust.”

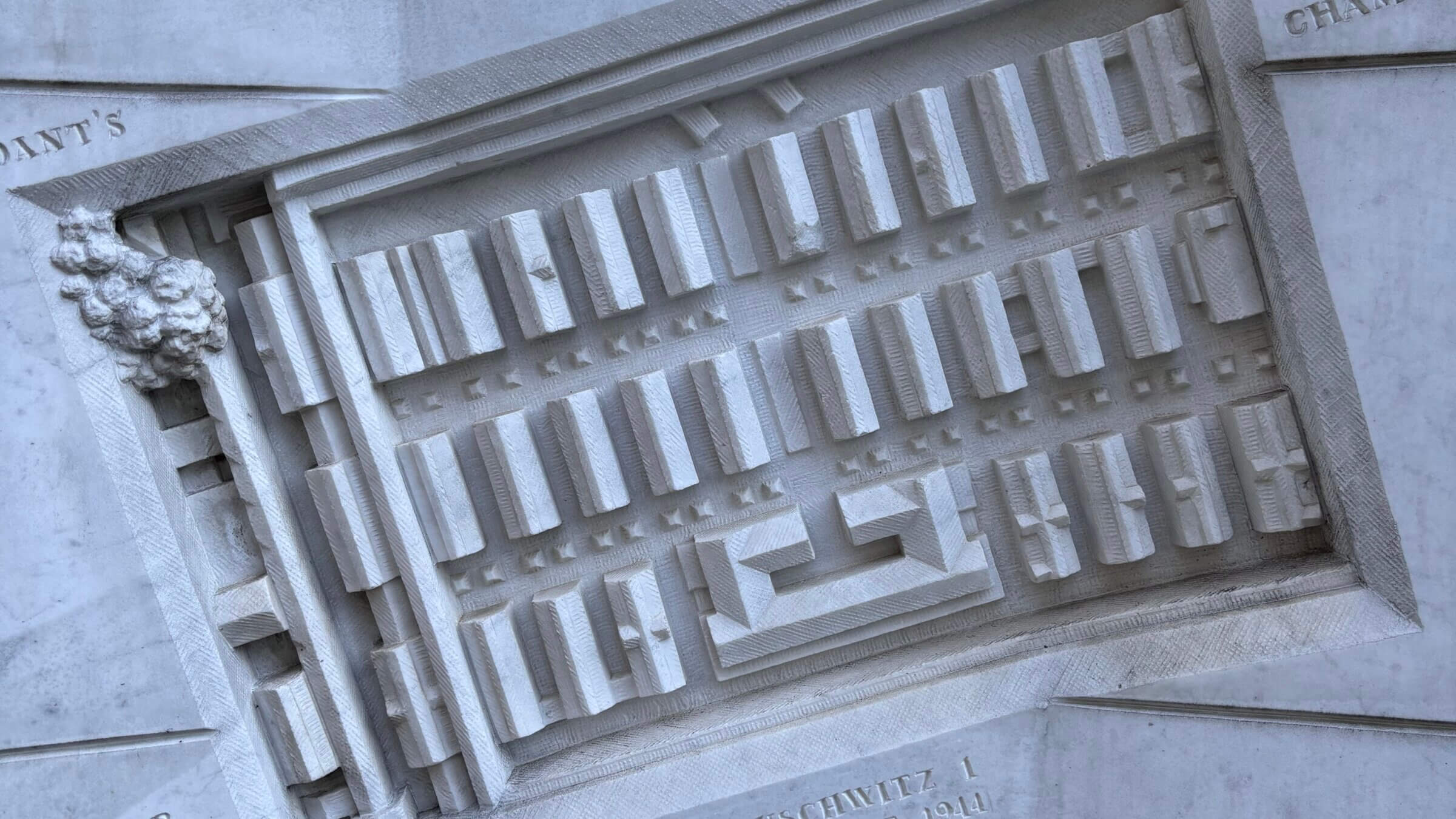

Feigenbaum’s Holocaust memorial depicts an aerial view of Auschwitz. Towering over it, a chimney engulfed in flames. Inscribed around the carving of Auschwitz are the words “Indifference to injustice is the gate to hell.” With its five-sided base column and six-sided upper column, Feigenbaum subtly references the 11 million people killed.

The chimney, which clearly references the horrific role of the gas chambers at Auschwitz, was inspired by Egyptian low-relief carvings. “It’s a play on the idea of the obelisks,” Feigenbaum said.

Feigenbaum won a competition in 1988 to create the memorial. “The furthest thing from my mind was that I would ever be considered for it,” she told me.” I hadn’t carved stone in years. They really didn’t have a clue.”

Feigenbaum started the two-year process of creating the memorial by making models which she brought to Italy where the basic shapes for the memorial were cut out with a giant saw. She then made drawings and returned to New York, where most of the process involved “on-site carving.”

“I used pneumatic hammers, which are terrible for your hands,” she told me, holding up her petite hands, “but it goes faster.” I asked if she would have done anything differently if she had created the memorial today.”I might hire five assistants,” she said with a laugh.

The image the memorial is based on comes from a series of photographs taken by Allied reconnaissance units under the command of the U.S. Air Force. The photos were taken during the bombing raids of an I.G. Farben synthetic oil and rubber complex near Auschwitz between 1944 and 1945. During the 1940’s, the I.G. Farben company relied on slave labor from concentration camps and was also a supplier of the poison Zyklon B, which was used in the gas chambers.

The images were stored in archives of the Defense Intelligence Agency after WWII ended and rediscovered and reanalyzed in 1978 by analysts from the CIA.

The existence of these photographs and the apparent failure of the Allies to act upon the knowledge they had gained from them is still widely debated. Did the Allies know what was happening in Auschwitz? And,if they did, why didn’t they act on that knowledge?

“Did you know that George McGovern, the presidential candidate, was one of the pilots who flew over Auschwitz?” Feigenbaum asked me. “That put to rest Roosevelt’s claim that it was out of reach. Suddenly it was really in reach.”

When I met with Feigenbaum, it was shortly before the presidential election. I asked her what she thought about the meaning and relevance of her memorial today. “It’s more relevant,” Feigenbaum told me. “Especially what’s going on with Trump. He wants to be Hitler. Indifference to injustice is the gate to hell.”