For an ‘adventuress’ who memorialized the Holocaust in art, a long-awaited revival

A new exhibit at Indiana University is bringing Anna Walinska’s work to a new audience

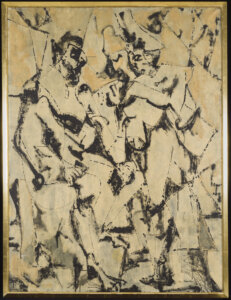

Anna Walinska with her painting The Naked and the Dead, which is now in the the collection of the Eskenazi Museum of Art. Courtesy of Rosina Rubin

Living in a heavily Jewish immigrant neighborhood in New York in the 1930s, painter Anna Walinska was surrounded by people who lost friends and family in the Holocaust. The trauma of this period prompted Walinska to paint a large series depicting the stories she heard and the despair that was felt throughout the Jewish community.

Although she received recognition during her lifetime, with exhibitions at the Jewish Museum of New York, the Gres Art Gallery in D.C., and MoMA, Walinska faded from popular memory after her death. Now, her work is being revived in Remembrance and Renewal: American Artists and the Holocaust, 1940–1970, an exhibition at the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University Bloomington.

Walinska was born in London in 1906, the eldest child of two Jewish immigrants and Forward contributors. Her father Ossip, who was born in Belarus, was once an opinion columnist and her mother Rosa, from Ukraine, published poetry. The Forward also serialized Rosa’s novel The Woman Who Conquered, about working in the garment district. When Walinska was three years old, the family immigrated to New York.

By the time Walinska was 12, she had developed a deep interest in art and began attending class at the Art Students League. At the age of 19, despite disapproval from her father, Walinska forged her own way to Paris where she studied under French Cubist painter André Lhote and lived amongst other creatives, including musicians, artists and writer Gertrude Stein.

Walinska moved back to the United States in 1930 after her brother, who had been studying economics in Berlin, warned that the situation for Jews in Europe was becoming precarious. She continued to paint and had her work shown in a number of exhibitions, sometimes alongside such artists as Andy Warhol, Wifredo Lam and Fernando Botero. In the middle of the Great Depression, Walinska opened the Guild Art Gallery in Manhattan, where Arshile Gorky had his first solo show in New York.

“She was a tremendous adventuress,” her niece Rosina Rubin told me. “And that’s the way that she projected to me as a kid, as a young woman growing up in New York in the 60s, that there weren’t boundaries, that whatever you wanted to do, you could do it.”

Rubin spent the first few years of her life living in an apartment on the Upper West Side with her parents, grandparents and aunt.

“It was a pretty interesting place to be as a kid because my aunt was in this world of artists, ” Rubin said. “As a child, I remember Louise Nevelson coming to visit and have the clearest memory of thinking that she was just one of the most interesting people I’d ever seen in my life.” (Nevelson was a sculptor, known for her experimental work with found objects.)

When Rubin’s younger sister was born, her immediate family moved to a new apartment. After her father died a few years later, Walinska stepped in as a second parent, often taking Rubin and her sister to art museums. Walinska stayed in the Upper West Side apartment until her death in 1997. She had converted one of the rooms into a studio and filled any available space she could find — bedrooms, closets, under the dining room table — with more than 2,000 pieces of art.

Rubin took on the task of cataloging all of her aunt’s work and finding the paintings new homes. Some were kept by family members while others were sold in order to pay for the cost of a storage unit for the rest. The most challenging task was finding exhibition spaces for the work — specifically, a home for Walinska’s large collection of Holocaust paintings.

Walinska had specified in her will that they all be exhibited together — an homage to a 1979 show she had done at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine — but had specified neither exactly how many pieces she had done or how this endeavor would be funded. Rubin estimates that the total number of paintings is more than 100.

Rubin explained to me that trying to re-surface the work of an artist who was not exhibiting at the time of their death is difficult — especially if that artist was a woman. Rubin says that one gallery owner told her that “the art world really has room to only showcase one woman at a time.”

“They already had one who was popular,” Rubin explained to me. “And so it was just not going to happen.

Rubin also believed finding buyers for the Holocaust paintings would be especially challenging because the work was “not commercial.” Unlike Walinska’s earlier paintings which had used bright bold colors, her post-Holocaust work was composed primarily of blacks, whites, and browns, meant to represent death, silence, and return to the earth, respectively.

Rubin was eventually put in touch with Jennifer McComas, a curator of European and American art at the Eskenazi Museum of Art, who wanted to include Walinska’s work in an exhibition of post-war art centered around the Holocaust. One of her boldest and biggest canvases will be on display.

“One of the things that’s interesting about that is you sometimes see the same faces occurring in different works,” Rubin said. “ Sometimes the face is in a painting that is called The Victims. And sometimes it’s in a painting that’s called The Survivors.”

“What it said to me was that any of us at another time in another place, maybe even now, we could have been a victim,” Rubin said. “She often said that those of us who were living were all survivors. We’re survivors of what happened. We carry the stories with us.”

Although it was emotional to part with some of her aunt’s pieces, Rubin knows the work was made to be seen.

“It’s very heartwarming to me that now collectors are really starting to express interest in the work that was specifically done in response to the Holocaust,” Rubin said. “And people are articulating that they want to hang art where they feel a connection to their heritage.”

The exhibition Remembrance and Renewal: American Artists and the Holocaust, 1940–1970 will be on display at the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University Bloomington from Sept. 4 to Dec. 14.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated Anna’s birthing order. She was the first child to two Jewish immigrant parents, not the second. Also, an earlier version misstated how many of her canvases will be on display. Only one, not multiple, will be on view.