In a bibliophile’s paradise, a treasury of Jewish manuscripts recalls a time when books were truly beautiful

At the Grolier Club, ‘Jewish Worlds Illuminated’ highlights of a vast collection from the Jewish Theological Seminary’s library

An early 18th century manuscript of daily prayers depicts a woman seated in her bedroom with an open prayer book. Courtesy of JTS Library

“One of the things that this exhibition does very importantly is to remind us of the vast range of places Jews have lived and made their homes and learned from the local cultures,” David Kraemer said.

Kraemer, a professor of Talmud and Rabbinics at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, was talking to me about the exhibition he has co-curated: “Jewish Worlds Illuminated: A Treasury of Hebrew Manuscripts from The JTS Library,” at the Grolier Club in Manhattan.

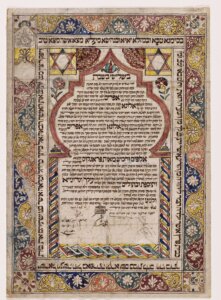

The free exhibition includes more than 100 manuscripts and books from 800 years of Jewish history in the Diaspora. Chosen from the rare book collection of the JTS Library, the exhibition features a letter signed by the philosopher Moses Maimonides, a 1290 German decorated prayer book for the Jewish High Holidays, an illustrated Passover Haggadah from Renaissance Italy and an 1875 Haggadah from Baghdad.

“These materials are the product of Jewish life, in very diverse areas of the world, from the 10th to nearly the 20th century,” said Kraemer. “We organized the exhibition geographically, according to lands in which the works were produced. When you come into the gallery, if you look to the right, all of the cases are devoted to materials that come from Jewish communities in Arab and Muslim lands. And if you go to the left, all of the cases are devoted to Jewish communities in Christian Europe. Jews have been at home in many different lands.”

The exhibition, he said, shows that Jews became very much “part of the cultures where they have made their home.” For example, Kraemer said, the depictions of life in the Arab Muslim world are very geometrical and sometimes resemble the Koran while Jewish artists in Renaissance Italy featured representations of animals as well as angels with human bodies.

“We have been misled into believing that the Second Commandment really did forbid the creation of images,” Kraemer said. “But Jews actually didn’t understand it that way. And so you see Jews culturally being part of the lands in which they found themselves. And this is an important lesson for today, because we too frequently hear the notion that there’s somehow a danger in acculturating and becoming like your neighbors — that we have to remain distinct. And certainly some distinctiveness is important for maintaining identity. But the evidence of the exhibition as a whole is that we were very much acculturated in the lands in which we found ourselves. We learned from the local culture, we became part of the local culture, and we contributed to the local culture.”

The exhibition is the largest ever of the Library’s Hebrew manuscript treasures and the first at the Grolier Club devoted entirely to Jewish books. Kraemer calls the manuscripts “vessels of memory.”

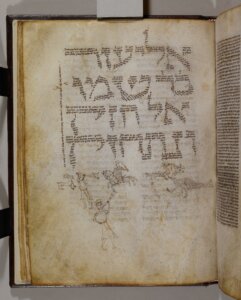

The manuscripts, he said, are all “individual products.”

“It’s not like printed books, where there might be hundreds or thousands of copies that are printed,” he said. Rather, he added, every manuscript is unique — “which means that a person paid for its production — the patron. The material that was acquired, the scribe who created it, the artists who contributed, all of those are individual to a given time and place — as well as marginal notes, as well as signatures at the beginning and the end. Every single one of these works tells us a story of the people who produced it and owned it over time.”

How were the manuscripts for the exhibition chosen?

“We have an immense collection,” Kraemer said, “so there were many things we couldn’t include. Where we have a smaller number of Jewish materials, say, from India or China, not enough to really form a coherent story, we excluded them. Once we came up with the geographical organization, which made a lot of sense, we just had to ask a combination of questions. What’s beautiful? What’s surprising? What will people be interested in seeing? We wanted some consistency. So people could actually go through from one case to another and do a tour of Haggadahs. We have Haggadahs from Spain and Italy and Germany and Egypt, and more. You could literally do a tour of the Jewish world just by focusing on Haggadot. And we have materials written by Maimonides and by Judah Halevi.”

I asked Kraemer to describe one work he found especially interesting.

“I get that question all the time. And, you know, it’s a very, very difficult one to answer, because there’s so many wonderful things here. And I would say that what I love today, I’m going to love something else tomorrow,” he said. “But one of the materials here, which I personally wrote the label for, and then loved seeing it in its setting, is a collection of sermons and other teachings, which was produced to manuscript in Salonica, in the 17th century. And the pages we have it open to are a very, very erudite piece of theology that asks the philosophical-theological question, how could Moses, who is of substance, flesh and blood, rise up to the heavenly realm, which is a spiritual realm, because philosophically speaking, there is a conflict, a tension, between the pure spiritual and the realm of substance. So Moses, of substance, how can he do that?

“That’s a very, very erudite piece of philosophical reflection, and when you look at the way the page is decorated, it’s very simple, almost like the illustration of a children’s book, with different flowers and plants, and these beautiful little, very, very simple, childlike drawings of animals that have nothing to do with the text. And for me, this captures what it means to be human. We can be very, very serious, and philosophical. And at the same time, our hearts really are lightened by the playful decoration and representation. And I love that combination.”

One goal of the exhibition, he said, has nothing to do with Judaism. The Grolier Club was founded in 1884 as a society for bibliophiles. “It’s the Grolier, so it’s about books,” Kraemer said. “When one looks at these manuscripts, I hope someone says, ‘Once upon a time, books were really beautiful.’ And maybe they’ll say to themselves, ‘And books should be beautiful again.’ ”

“Jewish Worlds Illuminated” runs until Dec. 27, 2025, at the Grolier Club, 47 East 60th Street, New York. The exhibit’s other curators are Sharon Liberman Mintz, the library’s Curator of Jewish Art, and Dr. Marcus Mordecai Schwartz, the seminary’s Ripps Schnitzer Librarian for Special Collections. Admission is free.