The double life of Abraham, from freethinker to pure believer

Anthony Julius’ novelistic and philosophic biography sees the patriarch divided by reason and faith

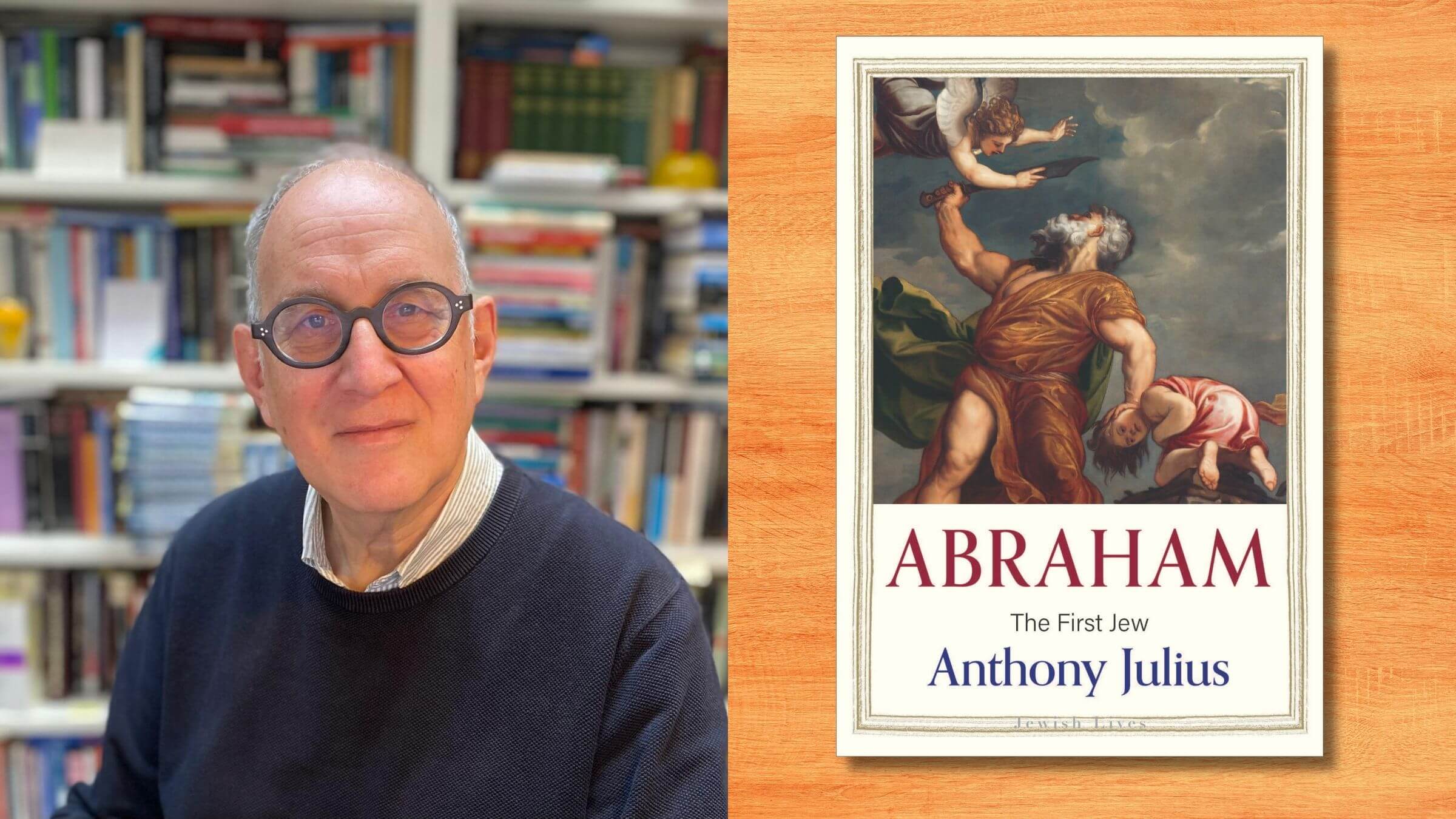

Anthony Julius’ Abraham: The First Jew makes a case for two Abrahams with radically different ways of being. Photo by Canva/Yale University Press

The Yale Jewish Lives series, which has volumes devoted to figures as diverse as Harry Houdini and Henrietta Szold, had a conspicuous gap in its library: an account of the first Jewish life.

In the new biography Abraham: The First Jew, Anthony Julius makes the case for the patriarch as the first “self-authored human being.”

As related in midrash, Abraham was a man who, through his own reason, determined that there was one God and challenged those around him to think for themselves. But in a twist, Julius, who has been fascinated by the binding of Isaac since he first encountered it in a comic strip as a boy, argues against Abraham as a unified personality.

If Abraham 1 was a philosopher and iconoclast, his near-death experience in a furnace at the court of Nimrod transformed him into Abraham 2, the person of pure faith who first appears to us in Genesis, heeding the orders of God to leave his home behind. Abraham 2’s inner life ends in terror on Mt. Moriah, when an angel stays his hand during his near-sacrifice of Isaac. There is no Abraham 3 — unless we count us, his descendants, who contain all his multitudes,

Julius, a writer and lawyer known for his defense of historian Deborah E. Lipstadt against Holocaust denier David Irving, has written a formally inventive overview of Judaism’s founder including novelistic scenes, debates and multi-pronged considerations of the story’s key events. (Julius said he wasn’t working as Abraham’s defense attorney, except against broadsides by Enlightenment thinkers who derided him.)

It is a text rich in allusions to philosophers, Romantic poets and midrash, capturing the existential dilemmas central to Jewish life and prefigured by our ancestor — a father figure so momentous even Freud had trouble handling his influence.

The duality of Abraham’s life is present in our own, Julius argues. We participate in his failures, triumphs and his “lurching” between critical thought to faith alone.

“Everything in the Abraham story feels profoundly resonant with our Jewish lives,” Julius said. “It’s as if it’s the first game, but it’s also the game that defines the rules of the game.”

I spoke with Julius about the two Abrahams, Sarah’s connections to suffragette thinkers and why more of us should follow the example of Abraham 1. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You write about Jewishness as a tradition of dichotomies and introduce this new dichotomy of Abraham 1 and Abraham 2. Most people, I think, would draw the distinction with his name change — from Abram to Abraham — or with the covenant.

I think that’s a bit of a diversion.

Can you say more about that?

The first thought was there are these two Abrahams, and they map on to skepticism, enlightenment, think for yourself, challenge every orthodoxy, keep everything provisional. And on the other hand, faith, subordination, thinking the thoughts that have been thought by authoritative others.

This says something about the nature of Jewish life — or certainly my sense of my own Jewish life. In that sense, I think of myself just as a typical Jew, where you kind of lurch between one position and another, very unstably, like the spiritual equivalent of a drunken sailor, constantly looking for some point of equilibrium, which is always beyond one’s reach.

And then the last thought was: Isn’t it interesting that though there are these two lives, the Torah account very much is focused on the second life, and the midrashic account comes in as if to complete the picture. So what is the asymmetry about? It’s about the necessary bias within the faith towards faith, but it’s also about a partly suppressed, partly return of the repressed, midrashic account, which speaks for skepticism. Those, if you like, are the stages of reasoning, and which I then thought was best rendered, at least in part.

Even when you write that Abraham has “ceased to be a self governing, autonomous person,” there’s still something of the old Abraham, say, when he’s bargaining with God about saving Sodom if there are 30, then 20, then 10 righteous people there.

I also wanted to write about the political theory implicit in the Sodom bargaining where Abraham says, “Yes, of course, if it’s less than 10, I won’t continue to bargain with you,” from which I derive the proposition that you cannot be a good person in a wicked society, that there’s a minimum number of good people who need to sustain each other if anyone is going to survive.

A minyan. You refer to the Akedah, the binding of Isaac, as a “catastrophe,” obviously a pivotal one. You reject some views: that this is a test passed that is to be celebrated, and break down other ways that it could be read — it being about negotiating with failure, Abraham challenging his own openness to God. Is there one that is more appealing to you?

The point I wanted to make is that it’s irreducibly plural in its meaning. Maybe it’s related to the lurching idea that we have this slightly monomanic attitude towards religion, where we feel there has to be the one true answer and the one correct interpretation.

It’s not comfortable being both skeptical and a person of faith, being both Abraham 1 and Abraham 2, it’s not even comfortable just being Abraham 1 because you’re constantly confronting the limits of your own rationality. And it’s not comfortable being just Abraham 2, because you’re constantly confronting the limits of your own willingness to subordinate yourself, but then to put the two together. It’s, as they say in Yiddish, Shver tsu zayn a yid — it’s hard to be a Jew.

I’d love to talk about Sarah. You have her reaching her own conclusions about monotheism, honoring the Torah statement that she’s the greater prophet. It’s kind of a feminist text in that way.

In Lech-Lecha, it says Abraham and Sarah left “with the souls that they had made,” and that’s interpreted as they were both evangelizing. They were both preaching monotheism.

So plainly, Sarah had her own convictions and her own views. Well, how did she come to those? In my reading, I found that in Sumerian society there was this decline in the status of women and the goddesses in the kind of heavenly pantheon. So I thought, well of course, if you’re a woman, if you’re immensely disadvantaged because of your sex, and what’s more, you’re on the slide, that’s going to be a tremendous goad to thought, to critical reflection on your society, where you are, what kind of a life you’ve been given and whether it’s acceptable to you. For Abraham, it was pure thinking. For Sarah, it was reasoning from her own given conditions. It’s not a kind of relaxed intellectual engagement.

I took a lot of my thinking from suffragette texts and feminist writers, because I wanted to get inside that tradition of thinking, independent women, discovering philosophy out of the pressure of need to understand their situation

If you look at the index here, we have midrash, we have the account in Genesis, we have Kant and Wordsworth and Levinas. I felt like Kierkegaard, who wrote Fear and Trembling about the Akedah, had to loom large in any sort of approach to this. He’s not your main one.

He isn’t. It’s slightly mystifying to me, all these rabbis who don’t read anything outside of the canonic texts suddenly have this weakness, this tenderness for Kierkegaard. It’s as if he represents the kind of one recreational experience. But actually it’s a profoundly Protestant perspective he has, and I don’t think it has very much to offer to Jews.

We’re all heirs to this tradition of Abraham 1 and Abraham 2. You think there’s not enough Abraham I right now.

Everybody knows what they think. Everybody knows what their position is. I was thinking about every Jewish group which knows exactly what it thinks about things. Jews nowadays are too comfortable in their slightly petrified sectarian identities.The tradition is so rich in self interrogation. It’s hard to understand why that is disregarded in favor of simple frozen positions, wherever they are in the spectrum.