What was the Jewish record on slavery? It’s (very) complicated.

Richard Kreitner’s ‘Fear No Pharaoh” unpacks the myths surrounding Jews and slavery in and around the Civil War and its aftermath

Judah Benjamin is one of the biographical figures considered in Richard Kreitner’s ‘Fear No Pharaoh.’ Photo by Wikimedia Commons

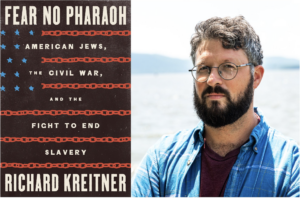

Fear No Pharaoh: American Jews, the Civil War, and the Fight to End Slavery

By Richard Kreitner

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 416 pages, $32

The central thesis of Richard Kreitner’s Fear No Pharaoh is unsurprising: In the 19th century, American Jews, like their compatriots, were all over the map in their attitudes toward slavery.

Geography was a key factor, but not necessarily determinative. Some Jews in the South were slave owners. But some northern Jews were slave traders; others were abolitionists; yet others chose to sit on the antebellum sidelines or inhabit the (shrinking) ideological middle ground.

Kreitner posits that the diverse Jewish reactions to slavery, secession, the Civil War and its aftermath had complicated roots. They reflected differing interpretations of Jewish tradition, plus a desire for acceptance and a fear of antisemitism. He attempts to unpack these nuances, in part, by examining six historical figures, all immigrants.

His principal subjects range politically from Judah P. Benjamin, the famous Louisiana lawyer, U.S. Senator and Secretary of State for the Confederacy, to August Bondi, who bore arms alongside the radical abolitionist John Brown in the contested territory of “Bleeding Kansas” before the Civil War.

Also firmly on the abolitionist side were the atheist and women’s rights activist Ernestine Rose, the only woman of the six, and the uncompromising Baltimore Rabbi David Einhorn. “Slavery is immoral and must be abolished,” declared Einhorn, who was later forced to resign his post. [I]f the Union is based on immoral foundations, it is not fit to survive.”

Two other rabbis profiled by Kreitner espoused views that have aged less well. Isaac Mayer Wise, the founder of American Reform Judaism, counseled a silent neutrality. To Wise, preserving the United States as a Jewish refuge “meant keeping quiet about the oppression of others,” Kreitner writes. New York’s Orthodox Rabbi Morris J. Raphall, by contrast, cited scriptural texts in defense of slavery, while acknowledging that the brutal American version fell short of the standards of Mosaic law.

It is not quite accurate to call Fear No Pharaoh a group biography, itself a challenging genre. Kreitner is trying for something even more ambitious: a comprehensive cultural history of American Jews in relation to these charged 19th-century issues and events. He touches on the career of the Lehman brothers, who made a fortune in the cotton trade before turning to banking; the Newport, Rhode Island, slave trader Aaron Lopez; and the U.S. War Department’s telegraph operator, Edward Rosewater, who did not, contrary to myth, transmit the Emancipation Proclamation.

Many other names pop up briefly. So, too, do milestones such as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s notorious General Order No. 11, expelling Jews from Union-occupied areas of Tennessee, Kentucky and Mississippi. An overbroad attempt to address black-market trading, the 1862 order was rescinded by President Abraham Lincoln about two weeks later.

The author’s point is to show that “the story of slavery and white supremacy in America and the story of Jews in America,” often told separately, are, in fact, “thoroughly intertwined.” Kreitner, who has written previously on secession and literary travel, accomplishes this intertwining with fluidity and grace. But the profusion of characters and detail and the attendant narrative detours weigh the book down.

Among the conflicts Kreitner identifies is the tension between the demands of ethics and social justice and the desire of Jews to assimilate and prosper. As long as Blacks were enslaved, Jews had little problem maintaining their precarious status as “white” in a race-conscious society, he argues. Antislavery advocacy potentially imperiled that status, Kreitner suggests — or so some Jewish leaders believed. It didn’t help that the abolitionist movement was imbued with Christian fervor and often struck anti-Jewish notes.

The Jewish history of persecution and pogroms in Europe, as well as the biblical narrative of Exodus, provided an ideological counterweight. Enshrined in the Passover ritual, the story of Israelites escaping from bondage in Egypt was coopted as a powerful metaphor by both enslaved Blacks and their Civil Rights-era descendants — and re-appropriated by Jews, Kreitner says.

The best-known of the book’s main characters is Benjamin, the subject of several biographies. Kreitner repeatedly laments that the former Confederate managed to burn most of his papers, a grave loss to history. Even so, he emerges as a profoundly charismatic and gifted figure.

In 1842, in defending an insurance company, Benjamin riffed on Shylock’s famous soliloquy from The Merchant of Venice to underline the humanity of enslaved Africans. But after he became a sugar plantation owner and U.S. Senator, his rhetoric changed. He embraced secession, predicted war and was dubbed “the brains of the Confederacy.” In February 1865, in a last-ditch appeal for manpower, Benjamin proposed that the South emancipate its enslaved workers in exchange for enlistment in the Confederate Army. The proposal, unsurprisingly, went nowhere.

Benjamin was not the only figure whose views evolved. After Lincoln’s April 1865 assassination, the previously noncommittal Wise seems to have been radicalized. His eulogy exhorted his listeners to “be the chosen people to … break asunder, wherever we can, the chains of the bondsman” and “the oppressive yoke of tyranny.”

Tracing this ambiguous history, Kreitner finds the roots of the Black-Jewish civil rights alliance, “never as stable or secure as often imagined.” Still, he chooses optimism over despair, borrowing the idealistic words of Bayard Rustin, organizer of the 1963 March on Washington. Fighting for justice “is your heritage,” Rustin told his Jewish allies in commemorating Temple Emanu-El’s 125th anniversary in 1970. “Let nothing tear you away from it.”