How Philip Roth invented a myth called ‘Philip Roth’

In ‘Philip Roth: Stung by Life,’ biographer Steven J. Zipperstein reveals the truth behind the rebellious character the author created

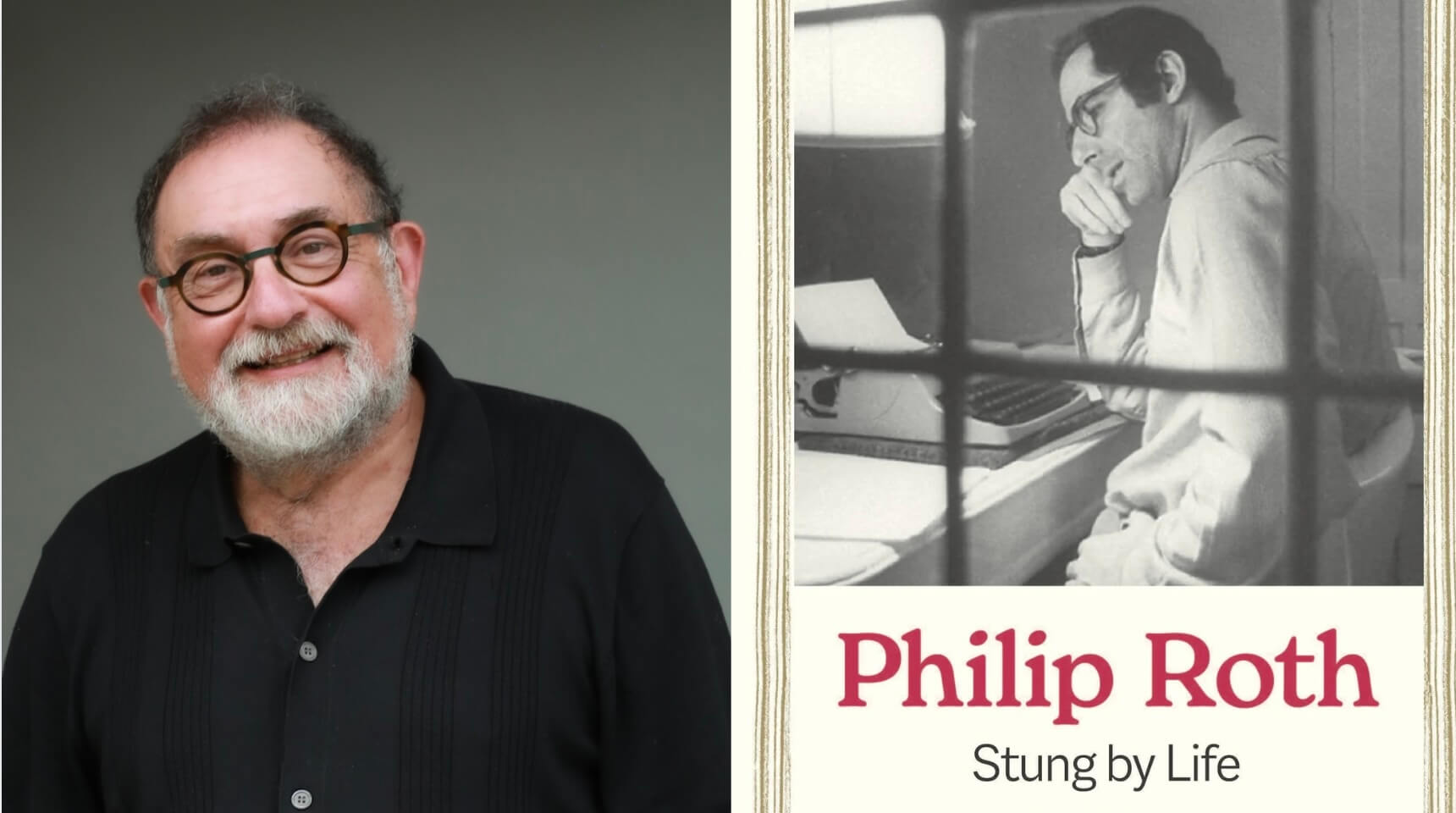

Steven J. Zipperstein is the author of Philip Roth: Stung by Life. Photo by Nan Phelps/Jewish Lives

Steven J. Zipperstein set to work on his own biography of Philip Roth before anyone knew that Roth’s authorized biography would be pulled from shelves after accusations of sexual misconduct by its author, Blake Bailey. Zipperstein and I first spoke when he was wrapping up his draft. He was pondering Roth’s legacy. He wanted to discuss a Roth-like character I had put in my novel, How I Won a Nobel Prize, in part because he was surprised to discover a younger writer riffing on Roth so openly.

Zipperstein’s book, Philip Roth: Stung By Life, which is part of Yale’s Jewish Lives series, distinguishes itself with an approach that focuses more on Roth’s intellectual and artistic development than on a comprehensive reconstruction of his sexual history. Though Roth was devoutly antireligious, Jewishness is a major theme that provides a surprisingly sturdy handle with which to grasp the family ties and cultural traditions that remained Roth’s persistent obsessions on the page, even as he resisted them in life.

Zipperstein, who is a professor of Jewish history and culture at Stanford, delivers an admiring, thorough, and swift account of an immensely single-minded writer’s unabating struggles with ambition, romance and the politics of his time. The book also has some fascinating scoops‚ major interviews and materials to which Zipperstein alone had access. We had a lot to talk about, and this interview has been compressed for length and clarity.

Start with the obvious: Why did you devote so much time and thought to a Philip Roth biography when there were rival biographical efforts that you could not have known would go up in flames?

Roth first reached out to me after I published my book, Rosenfeld’s Lives, and we were in touch intermittently for years. I was persuaded that there was really a book to be written, that I could actually do something new, when I discovered the Yeshiva University tape and came to realize the vast discrepancy between what Roth actually experienced and what he believed he experienced and then recorded on the page.

The Yeshiva University tape is one of one of several remarkable bits of journalism on your part, unraveling a remarkable bit of self-mythologizing on Roth’s part.

As part of its 75th anniversary celebration in 1962, Yeshiva University sponsored a panel about the ethnic responsibilities of a writer. Roth, who had at this point published only Goodbye, Columbus, was a featured speaker alongside Ralph Ellison. What Roth remembers — he devotes an entire chapter to this incident in his memoir — is that it was an inquisition, the audience hated him. As a result he decided he wasn’t going to write about Jews anymore and devoted three excruciating years to his next novel in which there are no Jews, and it’s a defining moment in his life.

I learned that the event was taped. Roth had threatened the university with a lawsuit if it was published or aired, but he agreed to give me access. By the time I acquired it, Roth was already dying in the hospital, so the last conversation I had with him was about this tape. It contradicts his memory in every conceivable way. The audience loved him and laughed at his jokes. Those who disliked him rushed to the stage once the program ended. And their criticism was all that he recalled.

I now see Roth’s purported rejection by the Jewish mainstream as a tale he invented (and earnestly believed) in order to justify his preexisting sense of rage and alienation.

Rage was a crucial factor in Roth’s fiction from the beginning. One of the people who contacted me, partly because of the implosion of Blake Bailey’s biography, and because of the apparent difference between my life and Blake’s, was Maxine Groffsky, who hadn’t spoken to anyone before about her relationship with Roth. They’d dated for years, and she was in many ways the model for Brenda Patimkin, the girlfriend in Goodbye, Columbus. But, at least as I was able to reconstruct it, Maxine was little like Brenda Patimkin.

She wasn’t rich or high status, and Roth was never especially subservient to her, the way Neil Klugman is to Brenda.

Still, in fiction Roth gives us Brenda Patimkin. That’s a projection of his rage and ambition.

Where do you think that came from?

I wrestled in the book not to be reductionist. I try to suggest that to understand Roth, you really need to understand the interplay between Roth and mother. Her fastidiousness was through the roof. Roth and his brother Sandy wouldn’t even use the bathrooms in friends’ houses because none were as clean as theirs. That’s a category of a very special kind. It’s a feature of Roth’s life from the outset to figure out what it means for him to really want to satisfy her and at the same time to be aware of what Benjamin Taylor calls his “inner anarchy.”

Mickey Sabbath — a rageful, overweight, unkempt, disgraced, perverted puppeteer — seems like the character through which Roth expressed his “inner anarchy” in its least-filtered form.

This man who engages in daily exercise, who’s trim, who’s incredibly disciplined in his work habits: Mickey Sabbath is what he imagines he is on the inside. In Sabbath’s Theater, he’s undressing himself. He’s allowing the reader to come closer to all that he fears he could be, the person who he knows exists and that he keeps hidden. It’s a book very much in conversation with Maletta Pfeiffer.

They had an on-and-off affair for more than 20 years, and she’s the model for Drenka in Sabbath’s Theater.

I think Maletta more than anyone else becomes privy to Roth’s secrets because he’s convinced that he’s met someone who has an all but identical attitude toward life, towards sensuality and sexuality, and who for the longest time he greatly admires.

But he’s wrong, isn’t he? You spent time with Maletta, and she showed you her diaries and her unsent emails to Roth — documents she never showed to any other biographer or journalist. I’m going to quote from your book, because I think this has real importance for how we interpret the portrait of mutual sexual ecstasy in Sabbath’s Theater. In one of her draft emails in 1995, Maletta wrote: “All the things you did to me. You made me go and talk to whores. … That never excited me. I just did it to please you. … I never liked it. All the things I did with you. I cannot even write about them. What you put in the book.” It’s quite dark to reconsider Sabbath’s Theater with the understanding that the model for Drenka was often not as enthusiastic as Roth believed her to be.

In contrast to the accusations against Blake Bailey, there’s no evidence of any coercive behavior on Roth’s part in his sexual life — but it’s clear that his sense of Maletta was, I think, not altogether accurate.

She’s romanticized, both in fiction and in Roth’s mind. This relates to a theme that I picked up on in your description of the arc of his career. Alongside his ambivalent relationship to Jewishness and family life, there is a parallel ambivalence between sentimentality and irony. Early in his career, he is so critical of Jewish sentimentalists like Leon Uris and Herman Wouk. But he has his own version of sentimentality emerge later in his career, particularly in American Pastoral and The Plot Against America. He becomes nostalgic for his parents’ world, for FDR, for the sense of moral security that he imagines they had.

He wrestled with nostalgia. He hated nostalgia, and he hated the strengths of family life. He is seeking his whole life to be extraordinary. But he also fantasizes, overtly in Portnoy’s Complaint, about the joy of not needing to strive, the joy of being mediocre. Roth deeply admires his father and wishes on some level that he was like him but also knows in every orb of his body that he wouldn’t actually want to be like him, committed and monogamous and dutiful. He writes from that ambivalence time and time again. And I think, as I suggest in the book, that’s why Zuckerman is the stand-in that stays with Roth, in a contrast to Kepesh, who is more one-sided and selfish and disposable.

I sensed your special affection for The Ghost Writer. Its portrait of writing within domesticity is extraordinarily well-rounded. Perhaps in response to criticism from Irving Howe, Roth maintains a balance in The Ghost Writer that he wasn’t trying to maintain in other works. And you argue, persuasively, that Lonoff is not really a portrait of Bernard Malamud, as is commonly thought, but is much more profoundly Roth’s projection of his own future.

Roth worked assiduously against balance and proportion in many of his other books. Zuckerman inhabits Roth’s ambivalence, and Lonoff represents a future that Roth doesn’t want. Roth fears obscurity. He doesn’t want a body like Lonoff’s, but he fears down deep that this actually might end up being his body. That Hope might end up being his wife. He’s able to face his own terror, in this book and others, in ways that I find extraordinary, especially since beyond his writing desk he doesn’t manage that nearly as successfully.

You surface Roth’s notion that politics is the great generalizer, and literature the great particularizer, and that at a fundamental level, they really cannot abide one another. “How can you be an artist and renounce the nuance? But how can you be a politician and allow the nuance?” Did Roth have political commitments?

He’s a political liberal in the Clintonesque sense, without using it as a curse word. But as is true for many aspects of his life, he’s willing to challenge his presuppositions. That’s something he certainly does in American Pastoral, which probably satisfied readers like Norman Podhoretz rather too much. He does something not dissimilar in The Counterlife with regard to Israel. His own inclinations are dovish. That book was all the more powerful for me for its capacity to portray with a degree of sympathy extreme Israeli figures that Roth politically deplored. One of the characteristics of Roth that I ended up admiring the most was the way in which he so often excoriated his own commitments, challenged them, and exposed them for their own weaknesses.

He tells Benjamin Taylor that he cares intensely about his “moral reputation.” That not something that one expects from the author of Portnoy’s Complaint or Sabbath’s Theater. How would you describe the values that Roth wanted to be associated with? It can’t be mainstream civility.

What he values above all is freedom as he understands it. And what he’s hoping a biographer will do is to portray him as someone who spends his life exploring the wages of freedom and the underbelly of unfreedom — hence his political commitment to liberalism, and hence his deploring ideologues who disparage freedom. He’s immensely preoccupied with his reputation, but he also takes incredible risks with it. He is insistent that those risks are unavoidable for a writer and that to avoid them means inevitable mediocrity.