In Nazi-occupied Paris, astute performances and direction elevate melodrama into a soul-stirring film

Fred Cavayé’s ‘Farewell, Mr. Haffmann’ is replete with twists of fate and reversals of fortune

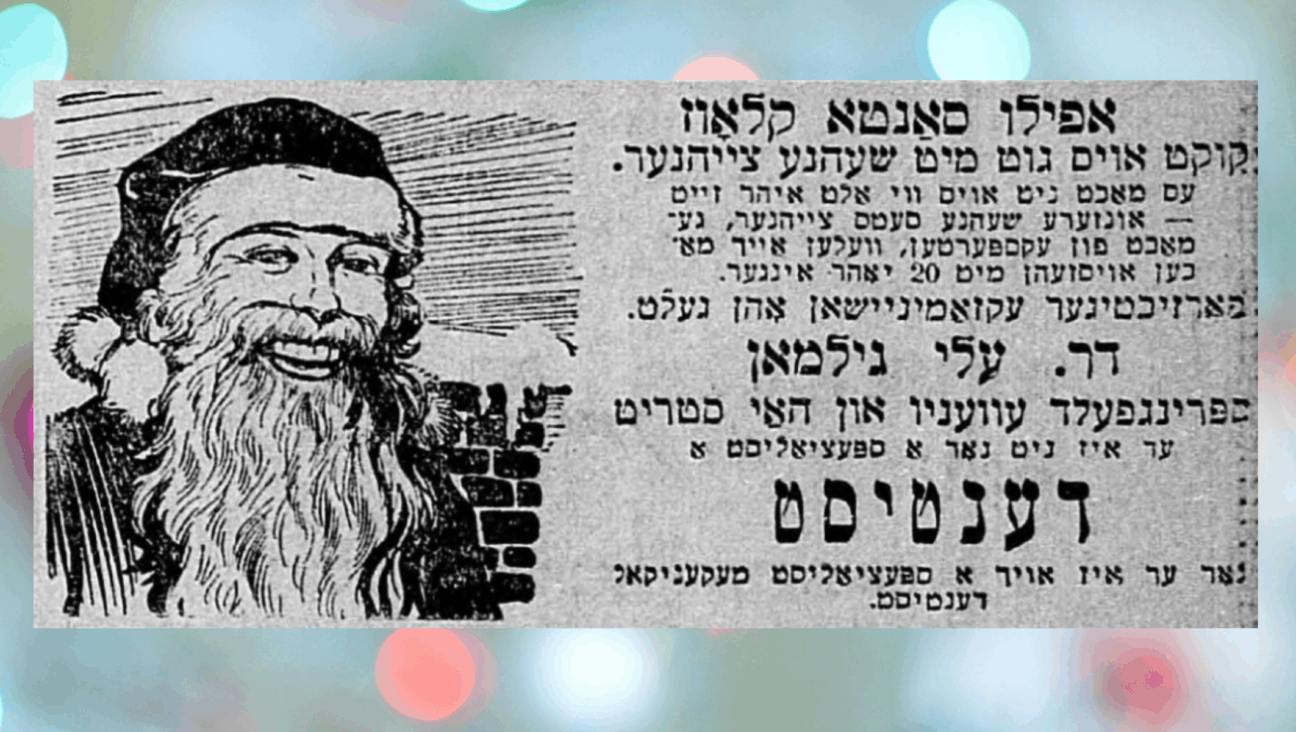

Gilles Lellouche and Daniel Auteuil star in ‘Farewell, Mr. Haffmann.’ Courtesy of Menemsha Films

You could argue that contrivance, dark farce, and even historical exploitation and trivialization are present in Fred Cavayé’s Farewell, Mr. Haffmann. Still, the psychological thriller dramatizes a morally complex and compelling Faustian narrative that touches on the power dynamics underlying class and gender inequality, antisemitism and, most central, the relentless brutality of the Nazi regime. The French language film is loosely inspired by Jean-Philippe Daguerre’s hit play.

The backdrop is occupied Paris, 1941, and members of the Jewish community have been ordered to identify themselves to the authorities. Anticipating what the future holds, a local Jewish jeweler, Joseph Haffmann (Daniel Auteuil, who gives a layered and nuanced performance) arranges for his family to escape the city and offers his non-Jewish employee, François Mercier (Gilles Lellouche) the opportunity to take over the store until it all blows over.

Both men recognize the bizarre and perilous proposition, which is made all the worse when Haffmann’s effort to escape fails and he, unlike the rest of his family who successfully fled ahead of time, is forced to return to the store and seek his assistant’s protection.

The store’s owner is now hiding in his own basement and dependent on his subordinate who for all intents and purposes has become the boss and is enjoying his new role. He and his wife, Blanche (beautifully underplayed by Sara Giraudeau) have moved into Haffmann’s well-appointed living quarters upstairs and Mercier is currying favor with the Nazi guards who are coming in to buy jewelry. He has also begun to design his own jewelry, fulfilling yet another lifelong fantasy.

Reversal of fortune, twists of fate, and the mutability of identity are pervasive themes. So too the fluidity of morality. Does one define morality by the intention or the result? The lines in this universe are shifting and blurred.

The most intriguing character here is the almost amoral Mercier, brilliantly conceived by Lellouche. He knows that Haffmann is in mortal danger and that it is right for him, Mercier, to protect him. But, as a physically disabled man who walks with a brace and has a limping gait, he is also motivated by his own social and economic ambition and his overriding self-loathing. Even if a tad overstated, it is dramatically and metaphorically fitting that he is unable to impregnate his wife, who wants to conceive a child, though not as obsessively driven as he is to sire one. It would be a self-redeeming act and proof positive in the eyes of the world that he is as virile as the next man.

Mercier pitches to Haffmann a stunning proposition: that he, Haffmann, impregnate Blanche. In this increasingly dehumanized world, in which Mercier has lost all self-respect, both Haffmann and Blanche have ceased to be autonomous human beings, but rather tools to further Mercier’s goals.

Blanche is at best a supporting character in the three-hander, yet she is the most well-rounded, contradictory figure here, at once docile and steely; hostile and loyal; submissive but no victim. She understands the limitations of her choices and her keen intelligence is evident. She blames Haffmann for trading places with her husband. Before, Mercier was reconciled to the life he had. Now that he has tasted a life that is not his, “he wants everything!”

Outside, the Nazi presence is metastasizing. Jewish-owned stores have been abandoned and boarded up, swastikas are plastered across municipal buildings, and Jews are being rounded up and deported. Here, Cavayé subtly alludes to the French collaborators who exiled 75,000 Jews to death camps, most of whom were murdered. At the same time Mercier parties with Nazi officials at dressy, alcohol-fueled high-end events. He flirts with the women and is embraced by the men. “They’re not so bad,” he says.

Mercier is no Nazi. He is more a social climbing clown than a political animal. And, in a provocative narrative quirk, it turns out he is not totally wrong in his assessment of at least one high level Nazi. The latter knows Mercier is hiding Haffmann in the cellar, yet remains silent for reasons that can only be guessed at. Even in the most evil a touch of humanity can surface?

A crisis erupts when Mercier’s Nazi clients express dissatisfaction with the jewelry that he has designed. Now in the humiliating position of failed artist coupled with the sense of impending doom, he begs Haffmann to create the pieces that he will claim are his. For Haffman the proposition is hideous. Survival is at stake and he is being asked to forge trinkets for Nazis with gemstones stolen from Jews who have been deported. Outraged, cornered and diminished Haffmann is reduced to bargaining. “What will you pay me?” Suspense builds as their twisted relationship becomes evermore interdependent and claustrophobic with the growing menace of the Nazi presence.

There are many unsettling scenes throughout, not least Blanche guiltily sporting a dress owned by the absent Mrs. Haffmann and then spied by Mr. Haffmann who is passing by. Their eyes meet, neither says anything. Their mutual shame is palpable. Much is left unsaid in this film. The silence resonates on many levels. Often, it underscores the fraught act of each character intently listening for any and all untoward sounds hinting at intrusion and discovery.

The cruel and ironic conclusion at the intersection of crime and punishment, inequity and justice is the perfect coda. It’s to the director and actors’ credit that a movie which could easily have become by turns a manipulative or melodramatic or even foolish pot-boiler is in fact a torturous and soul-stirring film.