From legendary photographer Ralph Gibson, a brand-new lens on Israel

In Gibson’s exhibit ‘Sacred Land,’ a first-time trip to Israel proved to be a deeply spiritual experience

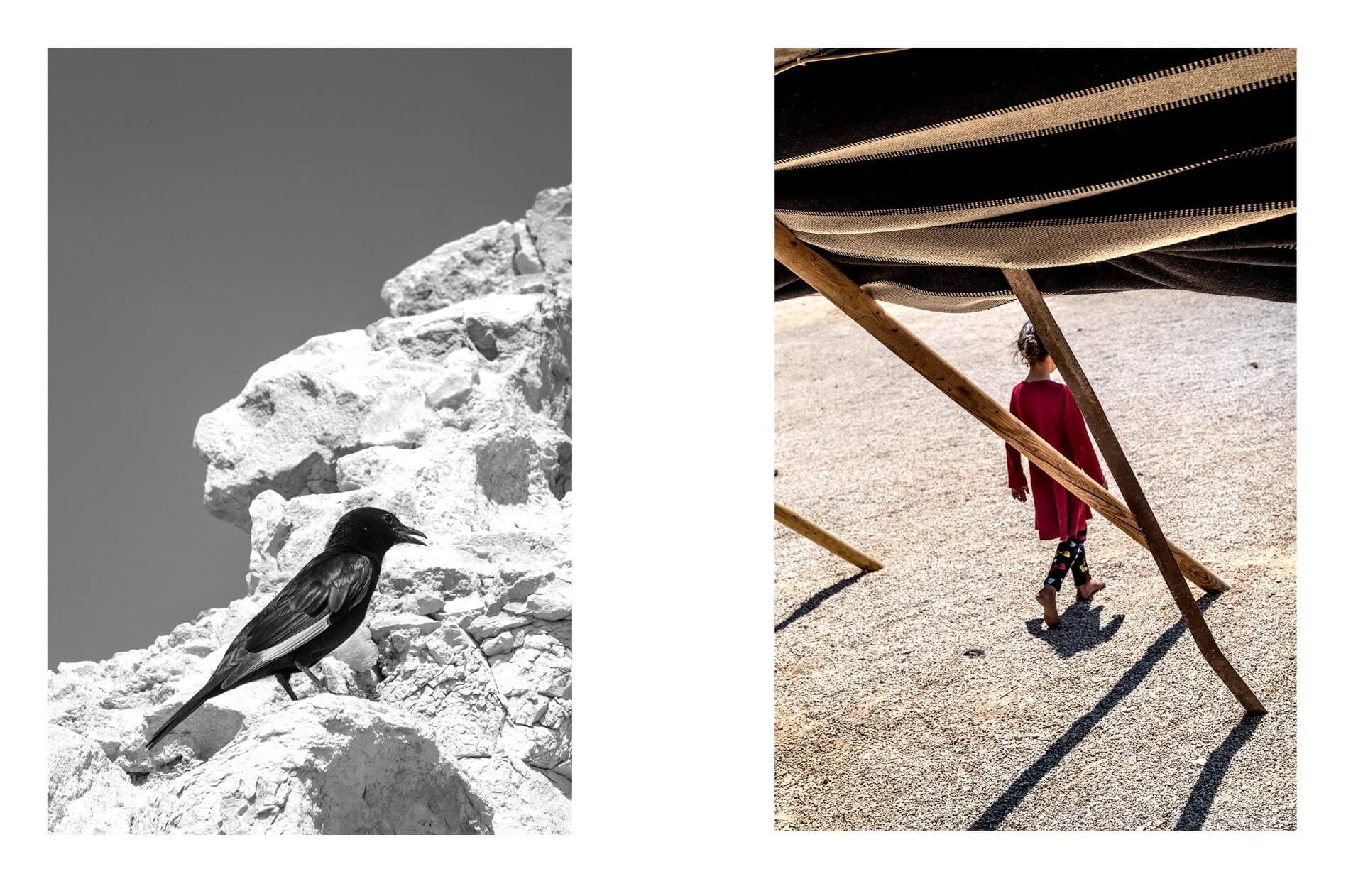

‘Untitled’ (Masada; Bedouin Village) Photo by Ralph Gibson

Ralph Gibson says that, when he was photographing Israeli faces, artifacts and landscapes, his “point of departure” was to explore the ancient and the new as juxtapositions and complements and everything else in between. “After all, it is the oldest and newest country in the world,” he told me.

What he uncovered was a complex and contradictory culture that embodies modernity and tradition; antiquity and technology; the personal and the universal; not to mention, at its core, a raw, primeval landscape awash in faith in all its manifestations.

Although he himself is a lapsed Catholic and a Pantheist, he said he found his first visit to Israel to be “a profoundly spiritual experience.”

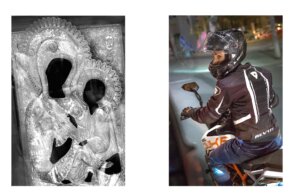

The result is “Sacred Land,” now on display in the soaring, expansive, very white, and brightly lit ground floor gallery at Hebrew Union College. The 68 pictures are an extraordinary amalgam of diptychs and solo photos; black and whites and color; closeups and distant shots; natural settings, city scenes, Israelis at prayer (Jews, Christians, and Muslims).

There are animal shots too. My favorite is his portrait of a camel head profile, its one visible eye sweet and gentle, its protruding teeth downright menacing. The image is at once comic, grotesque and innocent.

Gibson, who has had more than 200 solo shows to date and has published 40 monographs, is perhaps best known for his stark black and white photos, his abstract and surreal images evoking the work of Man Ray. His 1970 work “The Somnambulist,” catapulted him onto the global stage.

His “Sacred Land” shots, including dozens not displayed in the exhibit, are also available in book form, the vehicle he finds most authentic for conveying information, including the visual. For the artist, who founded his own publishing company, Lustrum Press 54 years ago, a book offers an intensely personal and immediate experience devoid of the social distractions inherent in a gallery setting.

He described his artistic process as “elliptical” — a picture may be shot or, for that matter, placed next to another shot in a diptych, for example, because of its subject or theme or, just as easily, its composition. The latter may be of purely aesthetic or cultural interest or, more usually, both.

Influenced by structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, Gibson said he is drawn to the shapes and signs of a culture. And many of these are shared across national, ethnic and religious lines. He pointed to a diptych featuring a shot of an ancient Torah curtain alongside a fragmentary bit of contemporary graffiti in Tel Aviv. Aside from the obvious contrast between the sacred and the secular, each boasts circular and oval designs, evoking both time-worn tradition and Cubisim.

‘This is not a travelogue’

Gibson is a mind-blowingly youthful 85-year-old with a fierce intellect who is not given to providing facile sound bites. Nonetheless, he was relaxed and easygoing, arriving to meet me in the gallery, hand extended.

Looking around the space, he admitted he did not like it at all initially, though he has come to view it as the perfect literal and metaphorical backdrop for an exhibit that celebrates humanism and universality. The cavernous room and lightness brings to mind “the dawning of the day,” he said.

The genesis of the project is a tad anomalous, almost harkening back to an era when artists had patrons. In this instance, the “patron,” Martin Cohen, dubs himself a “producer.”

When Cohen joins us in the gallery a few moments later, Gibson jokingly suggested he was interrupting our conversation “That’s all about me,” he said.

Cohen, a lifelong lover of Israel and a long time personal friend of Gibson’s, said he was deeply curious to see Israel through Gibson’s lens. So too was Jean Bloch Rosensaft, director of the Heller Museum who joined us as we walked through the space.

From the outset Bloch Rosensaft, who played a significant role in curating the exhibit, knew that through Gibson’s lens, “The most familiar, iconic shots would be seen as if for the first time. This would not be a travelogue. We’d be glimpsing larger truths.”

“It was 2018 and we were in Paris together with our wives when I asked Ralph if he had ever been in Israel,” Cohen recalled. “He said no but that he had always wanted to. And that’s how it began. Starting in March of 2019 and continuing for a couple of years we took three separate trips to Israel, each lasting approximately one week to ten days.”

“It was 19 days of shooting, which is absolutely remarkable,” Gibson added. “I don’t do commissions and I work autonomously. For me, this was an unprecedented collaboration. But I could not possibly have shot as many pictures as I did without Marty who organized the trip, including helicopter rides from place to place. In many ways, he was the director and I was the tripod.”

They toured the country, traveling from the most metropolitan sites to the old city with its vast diversity, “religious, ethnic, and racial,” said Cohen. “I wanted him to see the beauty and diversity of the land and people.”

“One of the most moving scenes to me was at the Jordan River, where a mass Baptism was taking place,” said Gibson. “There were hundreds of Christians of all sorts singing and chanting and reciting.”

“I was moved by the Ethiopians wearing yarmulkes,” noted Cohen.

“You usually see the power of faith in a negative way, but here it was just the opposite,” said Gibson. “I didn’t need to search for shots. This was a Garden of Eden, an enchanted project.”

While some shots were taken without the subject’s knowledge, in other instances Gibson requested permission. He asked one rabbi if he spoke English to which the rabbi replied, “‘only when I’m on Rivington Street,’” Gibson recalled..

Cohen said he was impressed with how comfortable Gibson seemed to be with his subjects.

“That’s because I’m old and not threatening,” responded Gibson.

Gibson grew up in Los Angeles. His father was an assistant to Alfred Hitchcock and Gibson spent time as a youngster on set and he continues to be influenced by film noir. He studied photography during his stint in the U.S. Navy and later at the San Francisco Art Institute.

He launched his career as a photojournalist, working on various newspapers and serving as an assistant to Dorothea Lange and assisting Robert Frank on several of his films. In 2010 he joined forces with Lou Reed and co-directed a documentary short, Red Shirley, recounting the life of Reed’s activist cousin Shirley Novick on the occasion of her 100th birthday.

But for the most part photojournalism never spoke to him in the same way as art photography, the latter reflecting his personal vision and perspective.

“Sacred Land,” he admitted, was a bit of a departure. “These photos are not about me, but rather about the sacred land. Although it’s my perspective, the subject came first,” he said.

‘A remarkable place’

The photographs here are not organized chronologically, geographically, or in terms of subject matter, but rather on an emotional level. The exhibit did, however, change direction in light of the Israel-Hamas war. The creative team chose to remove all military pictures (soldiers, bomb shelters, artillery) from the exhibit, though they are vividly present in the book.

Gibson opened the 220-page book to one of the more striking shots featuring a rifle, an image that fills the whole frame, and a female hand, nails manicured and painted, wrapped around the trigger.

“It’s the juxtaposition of the feminine with the weapon while pointing to the very real presence of the women serving in the Israeli armed forces,” Gibson said. But the photos on the gallery walls are galaxies away from a world under siege.

He said he believes the exhibit exudes a sense of hope and optimism and testifies to the possibility of a better future. For him, a self-described “sympathetic Goy,” the experience of being in Israel was transforming, starting with some of the widely held stereotypes that he believes have no basis in reality.

“The idea that Israel is apartheid is idiotic,” he asserted. “You have Christians of many denominations and Bedouins and Ethiopians and others representing the range of colors and origins. Israel is really a remarkable place and nobody talks about that.

“Had I not spent the time I did in Israel I would have swallowed the propaganda hook, line, and sinker. Of course I deplore what’s happening in Gaza, but when push comes to shove I want Israel to prevail. I know the difference between Israel and the rest of the Middle East — a desert. And then there’s this pearl called Israel. This is my humble opinion after having spent 85 years of life on Planet Earth.”