Fiercely committed and as unapologetic as ever, this 92-year-old artist is having a moment

In a new memoir and exhibit, Audrey Flack confronts the misogyny and antisemitism of the art world

In “Self Portrait with Flaming Heart,” Audrey Flack paints herself as the Virgin Mary. Image by Audrey Flack/Courtesy of Taggert Gallery

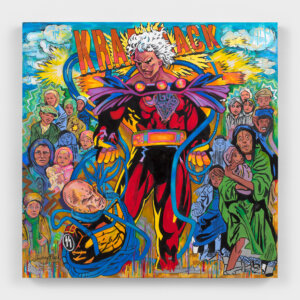

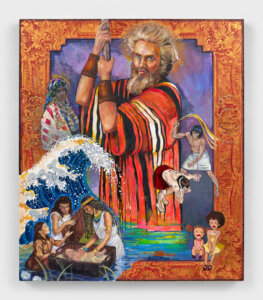

An exhibit of new paintings by Audrey Flack coincides with publication of the 92-year-old artist’s new memoir, With Darkness Came Stars. The exhibit, “With Darkness Comes Stars,” at New York’s Hollis Taggart gallery, features 16 paintings from what Flack calls her new post-Pop Baroque series, painted in the last three years and combining iconography from Marvel comics, Disney, and Judeo-Christian imagery. The memoir is an indispensable companion to the exhibit, illuminating the meaning behind the creation of these works.

The book takes us through pivotal moments in Flack’s nine decades as an artist, showing how she developed from a young hyperactive little girl into a young artist, then a wife and mother to two girls, one severely autistic, and left her first abusive husband and later found love again, all the while remaining fiercely committed to her need to create.

Art “on its highest level,” Flack writes, “bypasses the profane and deals with the sacred. Art kept me alive and still helps me cope with the most heartbreaking situations in my life. Art does that; it is the ultimate healer. In the midst of all the darkness that life can bring, art reminds us that with darkness can come stars.” By stars, she means bursts of light, inspiration, truth, connection, that art can bring about, by processing and surviving sadness, suffering, trauma and creating something that endures.

Much of the book details her grievances with how women artists were treated or ignored by dealers and curators. Often, she was the lone woman in a group of male artists, such as in the Whitney’s “22 Realists” exhibit in 1969. Once, even though she was a leader in the new Photorealism painting movement, she writes, she was excluded from a talk on photorealism by a gallery director who was showing only images by male photorealists, works that depicted “cars, trailers, motorcycles, trucks, storefronts, empty streets and deadpan portraits.”

“My colors were brighter, I used narrative and iconography, and my subject matter was humanist,” she wrote. Though she and the male photorealists were both interested in capturing light, she went on to say, they painted reflections on metal surfaces such as cars, and depicted the glass in car headlights and windshields, while she painted silver teapots and gold bracelets, and the glass in mirrors and bottles. She was interested in portraying emotion and expression.

That’s why, she explains, she was so taken with the expressive wooden statue of Mary, the Macarena Esperanza, created in the 17th century, which she went to see in Seville. The elitist art world looked down on this kind of art.

“They called it kitsch; it was too sentimental, too glitzy, with too much color and too much emotion. But I knew that I was standing before a masterpiece,” she wrote.

The custodian at the church told her the artist was Luisa Roldan, and said in Spanish, “of course the artist is a woman. No man could express the feelings a mother has for her son.”

This feminine aesthetic resonated with Flack. She didn’t care that elite art circles belittled Spanish Passion art for “its extreme emotionality and lack of classical restraint.” These criticisms were later used to characterize her work, such as when she painted her own image of the Macarena in “Macarena Esperanza” and “Macarena of Miracles” (1971), works that were deemed too colorful and too expressive, words often used as code for “too Jewish.”

Writing for The New York Times, Rosalyn Drexler called Flack’s painting “Jolie Madame” “one of the most beautiful ugly paintings I have ever seen.” The art world, Flack came to realize, was one “predicated on male vision, judged by male standards, evaluated by male critics, and written about by male art historians.” Her subjects were deemed too feminine.

When the Museum of Modern Art purchased her painting “Leonardo’s Lady,” Hilton Kramer complimented MoMA for “waking up enough” to buy the painting, but nevertheless referred to Flack as the “Barbara Streisand of the art world,” a remark one of Flack’s friends said was both misogynistic and antisemitic.

Like Flack’s memoir, her new paintings are unapologetic. They are lush and riotous with bright color and sensuous detail. In “Self Portrait with Flaming Heart,” she continues her obsession with the Macarena by painting herself as the Virgin Mary. At the center of the painting is the Jewish star she herself wears as a necklace. In these works, Flack reclaims Mary and Jesus as Jewish figures; here, Mary is a compassionate Jewish mother, whose heart is literally aflame in compassion for her child.

“We have strong powerful women,” Flack told me, speaking of Jews. “We have Queen Esther, but Mary is the one you go to when you are hurt, when you cry, I responded to Mary.”

In “Rex Judeus” (2003), Flack reclaims the figure of Jesus as Jewish, painting him wearing a tallit as a loincloth, evoking Chagall’s “Jesus in his White Crucifixion,” which he painted at a time of rising antisemitism before the Holocaust. Flack paints a smaller figure of the famous Jewish Warsaw boy with his hands facing up, begging for mercy, besides Jesus; perhaps this painting is a similar plea now for Christians to have empathy for Jewish suffering.

With Darkness Comes Stars is being exhibited at the Hollis Taggart gallery in New York until May 11.