Why did Judy Chicago take so long to acknowledge the importance of her Judaism?

Feminist artist Judy Chicago’s massive retrospective at the New Museum leaves out her history

Chicago’s stained glass window, showing a multiethnic, multi-religious Shabbat meal. Photo by Mira Fox

When a feminist artist named Judy gave herself the surname of Chicago — a way to rid herself of “all names imposed upon her through male social dominance,” she wrote in an announcement in ArtForum and a banner at her 1970 solo show — she wasn’t only shedding the names of father and first husband. She was also shedding any marker of her Judaism.

Much of Chicago’s artwork, now on view in Herstory, a massive retrospective occupying four floors at The New Museum, seeks to emphasize women and womanhood, which Chicago felt was overlooked or undervalued. The artist’s 60-year career, during which she’s been part of nearly every major art movement, has firmly enshrined her as a figurehead of Second Wave feminist art.

But Chicago’s work often neglects intersectional identities, approaching womanhood as a singular experience, fundamentally separate from maleness but just as fundamentally monolithic. Not only is that firmly out of vogue in today’s identity-driven world, but it also results in work that leaves little room for the multiple facets of Chicago’s own identity. Herstory emphasizes Chicago’s views on women in history, her struggles with male-dominated art movements like minimalism, but doesn’t work to contextualize her art with biographical or historical details outside of her feminism.

Yet it’s clear, in both large and small ways, that Chicago’s Jewishness was integral to her experience, both as an artist and a feminist

Chicago’s Judaism

Chicago comes from a long line of rabbis, going back to the Vilna Gaon in 18th century Lithuania; her father was the first to leave the religious fold, taking up the Jewish tradition of Marxist political organizing instead.

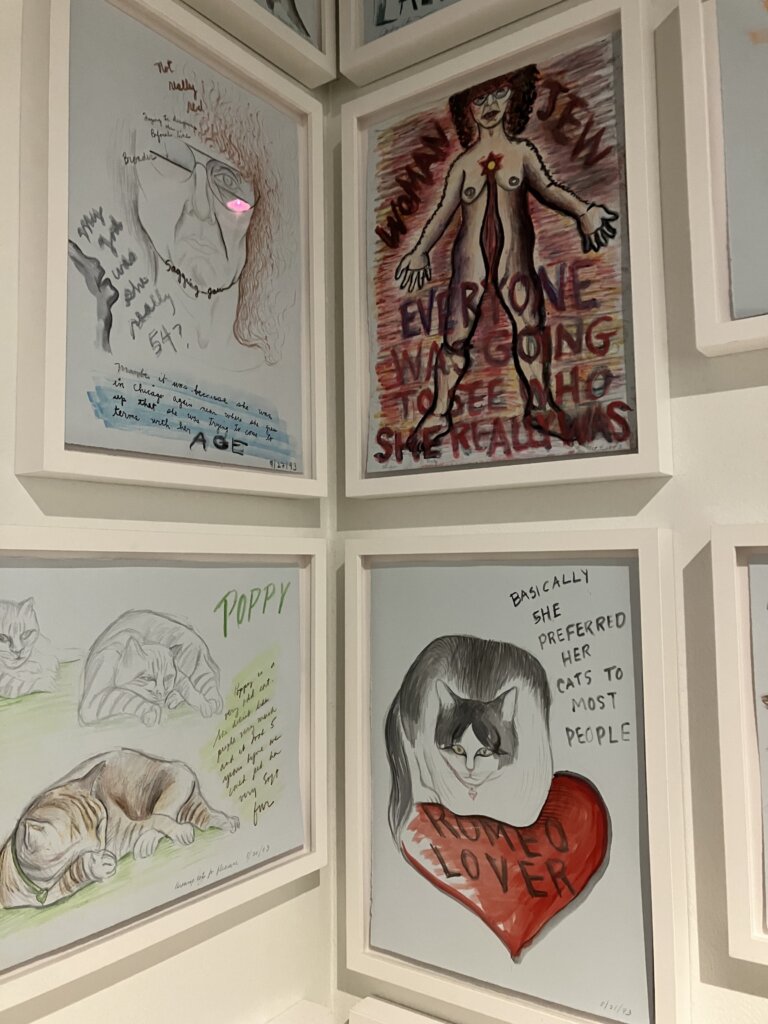

For much of her life, Chicago seemed to wish to distance herself from her Judaism, never exploring it in her work. Yet she couldn’t quite do it, as a small sketch, in a collection made as she was going through a period of depression, makes clear.

In a small nook, tucked into a stairwell between floors that is covered from floor to ceiling with rough drawings detailing Chicago’s anxieties about identity and aging — and her cats — there’s a striking, harsh red self-portrait of the artist naked and splayed. Scrawled across the sketch are the words: “Woman. Jew. Everyone was going to see who she really was.” A star of David emblazoned on her chest bisects the drawing.

And, indeed, in the 80’s, Chicago did finally openly turn to her Judaism. Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light, a collaboration with her third husband Donald Woodman, hangs in a dimly lit gallery on the second floor of the exhibit. According to the wall text, the project was “sparked by her and her husband’s joint realization of their relative ignorance about their shared Jewish heritage and history.”

Holocaust Project includes startling images, combining painting and embroidery with archival concentration camp photos. It centers on a glowing stained glass altarpiece, showing a Shabbat meal attended by people of many races, religions and nationalities, all watching as a woman in a tallit prays over the candles.

Intersectional identities

Much of Chicago’s work has since been criticized for its failure to engage with intersectional identities; womanhood, in much of her work, is a singular, uniting experience defined in juxtaposition to maleness. Her highlighting of female orgasm, birth, vaginal forms and overlooked women in history was groundbreaking in its time, but also clunkily literal. Today, much of the discussion around Chicago critiques her feminism as too white and corporate, often ignoring women of color, colonization and queerness.

Herstory does little to disrupt this narrative, or to engage with critiques of Chicago’s work. Much of the text in the exhibition focuses on Chicago’s desire to learn stereotypically male skills, such as auto body work. (She used these skills to spray paint vaginal forms onto car hoods.) Later, the exhibit frames Birthstory, a collection of fabric art depicting contractions, as a groundbreaking exploration of birthing, though indigenous women have been depicting pregnancy and birth for generations. And Dinner Party — Chicago’s most famous work, permanently installed at the Brooklyn Museum — lays out personalized table settings for women from history but does little to engage with the gaping distances between their experiences.

Though the works are powerful, they still feel somewhat lacking. In this way, Holocaust Project — and the handful of other Jewish pieces, such as a piece of judaica, a matzo cover — stands out in Herstory as one of the only places where multiple identities are able to overlap.

In the stained glass altarpiece in particular, ethnic and religious identities are reimagined alongside gender roles. The woman at the head of the table wears a tallit, though women are not traditionally given the prayer scarf. And people of many backgrounds gather at the Shabbat table, finding space within one religious practice to unify many. With this, Chicago offers not just a feminist way forward, but a Jewish one, and the work, glowing with hope, is more powerful for it.