How a Jewish mother from Flatbush became America’s most recognizable Italian on TV

For Levy’s Rye and Alka-Seltzer, you didn’t have to be Italian to play Italian — and Fran Lopate definitely wasn’t

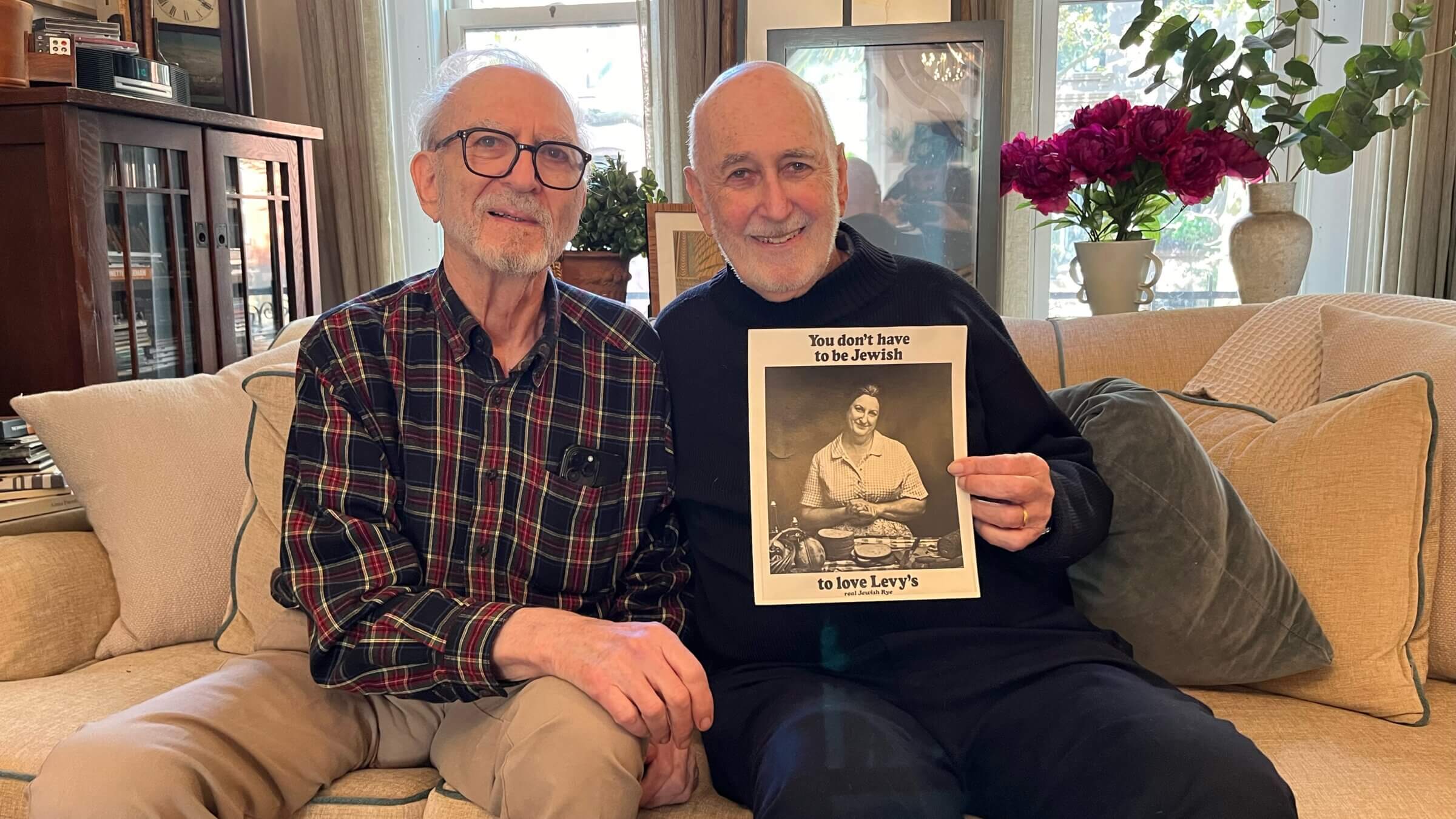

Phillip and Leonard Lopate and a photo of their mother Fran Lopate, spokesmodel for Levy’s Rye. Photo by Andrew Silverstein

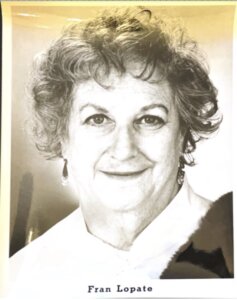

Fran Lopate, a 53-year-old former Garment District worker and Jewish mother of four from Flatbush, Brooklyn, was an unlikely model.

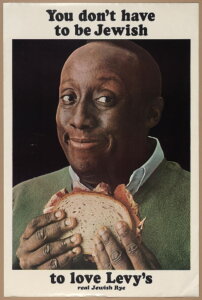

But in 1971, Lopate, in the role of an Italian mamma, her Jewish nose passing for Roman, stood behind a red-checkered table in one of the most famous advertising campaigns in American history, smiling warmly as she made a salami sandwich on rye. The text above her read: “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s real Jewish rye bread.”

Decades later, her son, the longtime radio host Leonard Lopate, who died Tuesday at age 84, remembered what it was like to see posters of his mother across New York. “It was all over the subways, huge posters, and I used to stand in front of her without ever saying, ‘Hey, that’s my mom,'” he told me last fall, sitting with his brother, the noted writer Phillip Lopate, in the living room of Phillip’s brownstone in Carroll Gardens. “But I felt very proud of it.”

Phillip had laid out artifacts of Fran’s brief moment of fame, news clippings about the ad and a TV commercial, headshots and playbills, and I had brought a packaged loaf of Levy’s rye. The two accomplished brothers, in their 80s, were trying to make sense of how their mother’s 15 minutes of fame as a fake Italian mamma was cut short by a real Italian mafioso, Joe Colombo, the head of the Colombo crime family and founder of the Italian-American Civil Rights League.

‘You don’t have to be Italian’

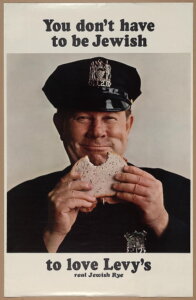

Lopate’s ad is the last of 10 posters in the Levy’s series that ran from 1961 through the 1970s. The ads, by the marketing firm, Doyle, Dane and Bernbach (DDB), feature non-Jewish New Yorkers like a Native American elder, a grinning Chinese man, and an overjoyed African American boy, feasting on Jewish bread, along with the same “You don’t have to be Jewish” slogan.

At a time when companies were expected to swallow their ethnic pride or turn heritage into caricature, Levy’s pitched their Jewishness as something everyone could value. And when marketers almost exclusively used perfectly symmetrical white blonde models, the series photographer Howard Zieff chose all Americans over all-American.

The ads started on New York subway platforms, but soon spread to billboards nationwide and a television spot, before taking on a life of their own. Unique in celebrating, not minimizing cultural differences, they were spoofed and mass-produced. In 1967, a poster printer reported to have sold more than 100,000 copies.

They remain a deli wall decoration favorite, and they are staples in marketing and sociology textbooks. In 1964, Malcolm X posed for a photo next to a Levy’s ad with an African American child for Now! magazine, saying “I like it.” and the sociologist Margaret Mead cited the ads as an example of social cohesion in her 1966 book, The Wagon and The Star. Today, however, they are often criticized for relying on stereotypes — cops are Irish, Italian mothers are overweight and over-doting, and in one ad not done by Zieff, an Asian man poses to karate chop bread. Plus, as many have pointed out, you don’t have to be white to be Jewish.

Praise now comes with a disclaimer, or outright suspicion. In 2002, the Poster House museum in Manhattan mentioned in an art wall label that there was a rumor that the Native American model in the Levy’s ad was an Italian shoeshiner.

For the Forward, I tracked down his identity: Joseph S. Attean, a Native American living in the Bronx. I told his story, but didn’t resolve the question of how we should view the ad today. At the time, Natives were inspired by seeing themselves positively depicted as part of modern New York, not relics of the past, but Attean is nonetheless dressed in a costume reflecting a Hollywood vision of an Indian.

The following year, I saw four Levy’s posters in the New York Historical Society, part of a traveling exhibit about Jewish delis. Attean was credited, but the other models, including Lopate, weren’t. So I set out to identify them.

I had read that Zieff’s subjects, with the exception of Buster Keaton, were unknown New Yorkers, with what he described to the New York Times in 2002, as “interesting faces, expressive faces.” To tell their stories would offer a snapshot of New York at a time when the city was starting to celebrate its diversity, but confront persistent stereotypes and tensions.

A mother’s tale

Unlike Attean, Fran Lopate wasn’t discovered, she was actively pursuing acting work. “She used to go around with her headshots and say, ‘I’m not just another pretty face,’” recalled Phillip.

Phillip, 81, retired in 2023 from teaching writing at Columbia University, and is working on a book about Washington Irving. Leonard, until his death, hosted a Sunday talk show on WBAI after accusations of inappropriate behavior toward female colleagues forced him out of his longtime WNYC radio program The Leonard Lopate Show in 2017.

Their mother Fran Beslow was born into a middle-class Jewish immigrant family in Boston in 1918. The youngest of 11, she was orphaned before the age of 12. Passed from sibling to sibling, she dropped out of high school and ran away. Cast out of her family in 1939 based on a false rumor that she slept around, she married Al Lopate, a ribbon-dying factory worker.

In taped discussions in 1984 between Fran and Phillip that became the basis of his 2017 book A Mother’s Tale, she said life had handed her “the shitty end of the stick,” with her husband most often to blame. The mother and son rehashed the physical abuse, suicide attempts, abortions and her multiple affairs under her husband’s nose, one of which produced her youngest daughter.

“We were very poor,” Leonard said of their childhood in Williamsburg, not far from where Henry S. Levy opened his bakery in 1888. “We lived on Broadway, where the elevated train goes by. When the train stopped people looked in the windows and said, ‘Who would live there?’ It was us.”

Phillip called the neighborhood a “shabby Jewish slum,” but their home, he said, had an artistic air. Al, was an aspiring writer, having lost his newspaper job in the Depression. Fran ran a candy shop, worked in wartime factories, owned a small camera store, and held clerical jobs in the garment industry. Still, with her middle-class New England roots and time performing in night clubs before becoming a mother, she felt superior to her fellow Brooklyn tenement dwellers.

“My mother was larger than life,” Phillip said. “Her emoting needed a larger stage than just the family.”

When teenage Phillip and Leonard joined a local Orthodox Jewish choir that didn’t accept women, Fran joined the church choir down the block to spite the rabbi. Then in the late 1950s, she got a job as a bookkeeper at M. Lowenstein and Sons, a Manhattan fabric company, which produced an employee musical revue. Leonard, then an aspiring painter, helped make the sets, and Fran became a Garment District diva.

“Jesus, I had lost all that weight and I really looked terrific,” Fran, then 66, recalled to Phillip in 1984, “I walked along the street like I had a broomstick stuck up my ass, great-looking behind, spiked heels on, all the eyes used to pop out of their heads.”

Soon, the mother of four, developed a nightclub act. “She would sing slightly off-color songs,” remembered Leonard, “like ‘I got the son in the morning and the father at night.” In 1968, at the age of 50, when her kids were mostly grown up, she quit her day job.

“I had finally decided it was my turn,” she later told Phillip. “Everyone got what they wanted. While I waited it out.”

After touring in the musical The Boy Friend, she posed for a cigarette ad in a Valkyrie costume with horns and a pointy brassiere. Then in 1970, she caught the eye of Howard Zieff, a 34-year-old director who New York Magazine called at the time, “the Fellini of Television Commercials” —noting that by not doing “‘pretty casting,” he had “done much to change the face, as it were, of television advertising.”

Mamma Mia!

A year before the Levy’s ad, in the same wig and makeup, Lopate stands behind the same table with the same red-checkered tablecloth and gives the same warm smile. Here, though, she serves a plate of spaghetti and meatballs to a mustached actor.

“Mamma Mia. thatsa spicy meatball,” the actor Frank is supposed to say after tasting the fictional Magadini brand meatballs.

But each time, he stumbles over the words or forgets the accent. By the time the director calls “take 59,” Frank cannot utter his lines or stomach another meatball.

“Sometimes you eat too much, and when it’s spicy,” a voiceover pitches, “Mamma mia do you need Alka-Seltzer.”

The ad within an ad created by DDB is considered one of the greatest commercials ever. “Spicy Meatball” instantly became a catchphrase, meaning something unexpectedly bold, food or otherwise. For Zieff, who later directed the movies My Girl and Private Benjamin, it solidified his reputation as a leading creative director.

Lopate, without speaking a line, along with the spot’s star, Jack Somack, a former chemical engineer, became overnight sensations. “After that, I was just going like a house on fire,” she told Phillip. “I made two or three commercials in the space of two weeks.”

In September 1970, she told New York Newsday about leaving M. Lowenstein: “They said to me ‘You’ll be back,’ but I meant it and never went back.”

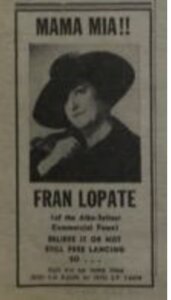

Two months later, she ran her own ad with her photo in the industry magazine Variety under the headline “Mamma Mia!!” It read “Fran Lopate (of Alka-Seltzer Commercial Fame) believe it or not still free lancing.” This would be her high water mark.

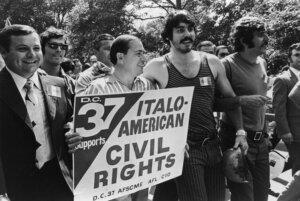

The Civil Rights movement had spurred Native American organizers, Chicano groups, and Women’s right activists, but there was no Italian advocacy group. Filling the void, Joseph Colombo, a Mafia boss, founded the Italian Civil Rights League, modeled after the Anti-Defamation League and 60s activists.

Colombo ran rackets and gambling rings, and ordered hits, but facing an aggressive FBI investigation, he vociferously argued, “there is no mafia.”

Italian-American Civil Rights League successfully campaigned for the FBI to stop using the terms “mafia” and “cosa nostra” in public statements and had the words struck from the movie script of The Godfather. The Alka-Seltzer ad, he said, was insulting to Italians.

Mixing 60s-style activism with strong arm tactics, Colombo might have been motivated by his own self interests, but his message resonated.

“The fact that some racketeers attempt to exploit for their own purpose the outrage felt by Italian Americans is unfortunate,” wrote Richard Gambino in his 1974 social history of Italian Americans, Blood of my Blood. “But it is besides the point.” The previous year, he had founded the nation’s first Italian-American studies department at Queens College.

Gambino argued in a 1972 New York Times Magazine article that Americans stereotyped Italians as either “swarthy, sinister hoods” like in The Godfather, or as “spaghetti twirling, opera‐bellowing buffoons in undershirts,” like, he said, “in the TV commercial with its famous line, ‘That’sa some spicy meatball.’”

With a possible Italian-American Civil Rights League boycott, the commercial was pulled in December 1970. Then the league, Phillip said, cost his mother a role in The Godfather and another movie, because she wasn’t an authentic Italian.

“I was Queen of the May, I made a lot of money, and I had a lot of fun ” Fran Lopate later told Phillip, “And then it somehow all dried up.”

But before it all disappeared, Zieff, reprised Lopate’s Alka Seltzer role one more time in a Levy’s ad.

A societal change

In 1971, most anyone who came across the Levy’s ad with Lopate, her hair in a bun and her motherly smile, would have been amused by the Alka Seltzer ad callback.

Contemporary critics, not in on the joke, are left confused. Drexel University Professor David Raizman in his 2021 book Reading Graphic Design History, closely examines the ads, questioning why Lopate is the only woman in the series, and the only one photographed standing behind a table, not a close-up eating a sandwich. “One even wonders whether the ‘Italian’ woman might just as well be a ‘Jewish Mother,’” he writes.

Another late 60s Levy’s ad features African American comedian Godfrey Cambridge. On the surface, as many have pointed out, it suggests that you can’t be both Black and Jewish, but it actually winks at the opposite. Cambridge had just played a Jewish cab driver in Sidney Lumet’s 1968 movie Bye Bye Braverman.

The comedian and civil rights activist was in on the joke. A 1969 New York Newsday profile includes a photo of him in his Manhattan apartment with a framed Levy’s ad poster with Buster Keaton. That year, the rye bread ad model was a choir boy. The clue that he is not Jewish, isn’t his features, but his frock — and searching through news clippings, I found he was a reverend’s son, and indeed, a choir boy, Paul Modean

The first Levy’s ads in the early 1960s are guilty of defining Jewishness by skin color or innuendo. When the Native American poster came out, one of the most popular television shows was The Andy Griffith Show, a nostalgic small town program with an all-white cast. Ten years later, the #1 show was All In The Family, whose diverse cast took race and gender politics head on. The last Levy’s ads reflect the societal change they helped foment through subtle humor — lost to modern audiences.

The genius of Howard Zieff

DDB was not an activist outfit, but at a time when Madison Avenue was dominated by WASPs, the mostly Italian and Jewish admen wanted to show their reality. “Advertising had portrayed this country as everybody with even white teeth, blue eyes, blonde hair,” the DDB art director Roy Grace explained in 1987 oral history of the Alka Seltzer ad, now part of the Smithsonian collection. “Nobody looks like that in the Bronx or Brooklyn.”

The spicy meatball ad is a commentary on the average Italian-American food commercial of the day. It may have been the first commercial to “let the wires show” — more than revealing the chaos of a film set, it exposes the fact that, in jarred Italian food ads, everything, including the accent was fake.

The ad copy writer Evan Stark described in a 2011 interview his inspiration for the script. “I suddenly remembered a spot I had done for Buitoni in Rome,” Stark, who passed away last April, recalled in a 2011 interview for the blog of the ad man Vinny Warren.

The 1960s commercial, which one can find on Youtube, features Roman boys with adorably bad accents tasting three different types of Buitoni pop-up pizzas, prepared by an over-gesticulating Italian chef. The first three boys each say which instant pizza flavor is his favorite; the punchline comes when the fourth, a chubby bambino, exclaims, “I love them all.” Mr. Buitoni pokes his belly approvingly.

“Well, nobody told the fourth kid that he wasn’t actually supposed to eat them on every take,” said Stark, “and what happened was that kid #4 got sick.”

The toaster-ready frozen “authentic” pizza, the cartoonish pizza maker singing “O Sole Mio” and the fat shaming of a child are all hard to stomach. It’s the opposite of Howard Zieff’s ads which showed ordinary people with all their wrinkles and flaws, without poking fun.

Lopate, with a bun, apron and Mona Lisa smile is a carbon copy of the doting homemaker in the Hunt’s “Oh, Mamma Mia wait till you taste” marketing campaign. From the early 50s to the mid-60s, the tomato paste print ads showed a glowing Italian mother serving homemade spaghetti, lasagna (called “noodle casserole”), and yes, “meat balls.”

Zieff, known for a maniacal attention to details, filmed the February 1970 commercial over 8 1/2 hours, going through 175 meatballs. The 51-year-old Somack improvised his character’s comical gaffes and wisely spit the polpetti into a bucket between takes. In the last hour, they added in the comedic crescendo of the oven door falling off once his character finally nails his line.

Zieff’s genius was hiring inexperienced non-Italian actors. “The more believable they were, the better the commercial.” Herb Seidel, who directed commercials with Zieff at Columbia Pictures in the 1970s, told me in a phone interview.

The Alka-Seltzer ad isn’t about Italians, it’s about non-Italians desperately attempting to perform Italian tropes. Or as Somack, who a couple years earlier had been a salesman, told the Chicago Tribune in 1971, “It’s about an actor who finally got a job and is going to make a commercial for spicy meatballs.”

But the failing actor was not the butt of the joke. At the end, when the director yells “Let’s break for lunch,” the viewer can’t help but sympathize with the over-stuffed actor.

Fran Lopate’s talent

In April 1971, DDB won top honors for the ad at the International Broadcasters Award series. In response, Joseph Colombo’s son and Italian-American Civil Rights League vice-president Anthony Colombo told UPI, “the league had assurances from Miles Laboratories, the producers of Alka-Seltzer, that the commercial will be removed from television.”

Except Miles Laboratories had already quietly pulled the commercial in December 1970 for what they described as “business reasons.” The New York Times and other media still credit Colombo with canceling the ad. Even if Miles Labs didn’t receive threatening calls from the league, Colombo, whose reign ended when he was shot at a league rally in June 1971 and fell into a coma from which he died in 1978, had spurred a cultural shift.

Italian-Americans have since embraced what was once deemed offensive. This month, the Binghamton AA baseball team called themselves the “Spicy Meatballs” in honor of the local Italian-American community — a celebration that would have been unthinkable in 1970, when Colombo’s group could cancel a television commercial and derail an actor’s career.

“They started wanting spokespeople who were not as ethnic. It went from one extreme to the other,” Fran remembered in 1984. “If they were doing an Italian mama commercial, they had to have an Italian accent, which I don’t have.”

She was passed over for a role in the 1970 romantic comedy Lovers and Other Strangers. “They decided they needed a real Italian,” Lopate said. “I could never compete with the real Italians.” In The Godfather, Lopate settled for being a stand-in for Morgana King.

Somack ran into similar problems. “For a while I played nothing but Italians,” he told the Chicago Tribune, “now I’m on a Jewish kick.”

Fran couldn’t make the switch. She might have been a Jewish mother, but not a stereotypical one. She had a New England accent, and as she put it, “couldn’t speak ethnically.” Besides, “they weren’t looking for Jews, because Jews weren’t “in,” she said, “Italian was ‘in.’”

At the time, Phillip felt inspired to pen a poem. “Now I don’t speak much to my mother: she’s become a star, I see her in the subway advertising Levy’s Jewish Rye, pretending to be Italian,” he wrote, “though she’s getting a nose job. Imagine, at fifty-three years old!”

“Do you know what history it takes to build a nose like my mother’s?” Phillip asks before lamenting the “Cossack sabre on my mother’s nose.”

Without the nose that caught the eye of Howard Zieff just the year before, she just looked like an average middle-aged woman. Her career sputtered, but she never regretted it.

She found stage work in dinner theater and touring companies playing Golda in Fiddler on the Roof. She finally divorced her husband, went back to school, and performed in senior productions until she passed away at 81 in 1999.

“She always promised herself to divorce my father. She always promised herself a nose job,” said Phillip. “And eventually she got them.”

“It’s a funny thing, this whole business about being a false Italian and being Jewish, but not Jewish enough,” Phillip reflected now decades later. Colombo derailed his mother’s career, but he said “it was not a tragedy.”

“She had a talent, and took it as far as she could,” he explained. “She was never going to become Barbara Stanwyck,”