The secret Jewish history of The Who

In honor of guitarist Pete Townshend’s 77th birthday, we return to investigate the band’s surprising Jewish resonances.

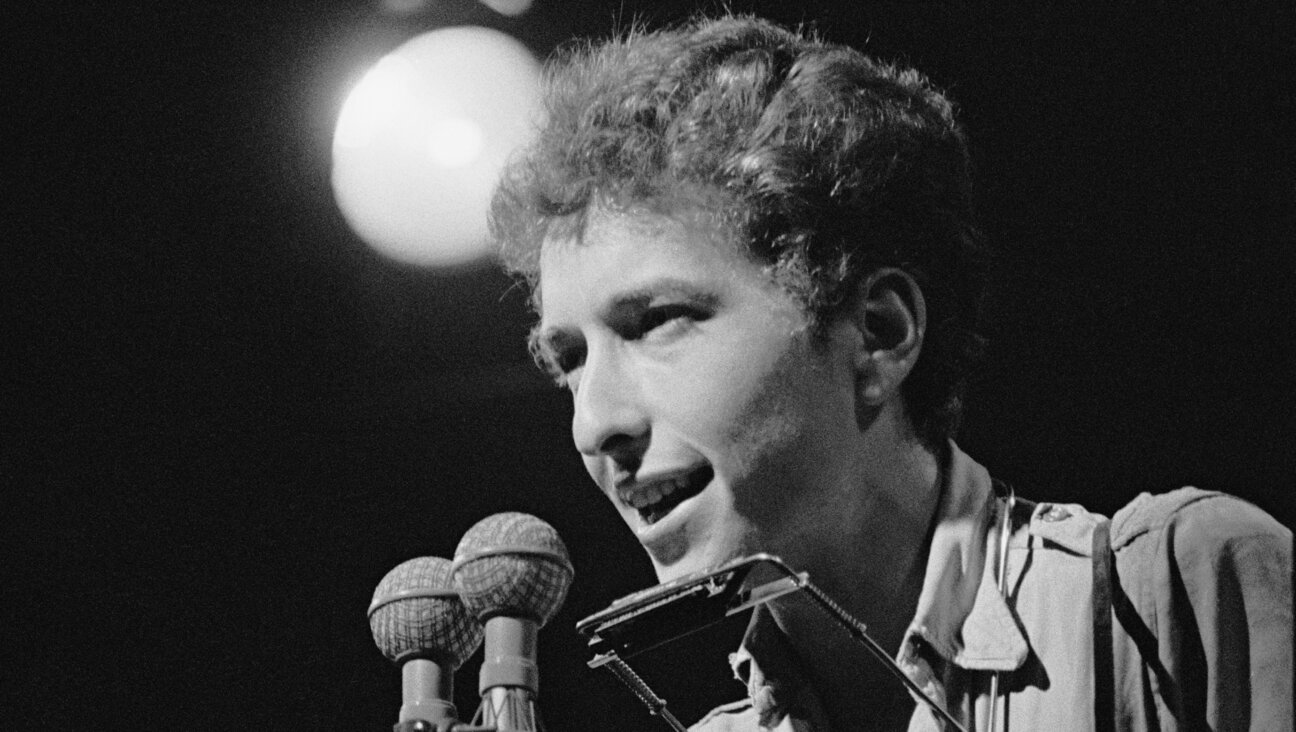

Who’s Jewish? Pete Townshend, circa 2000. Image by Getty Images

Editor’s Note: In honor of Pete Townshend’s 77th birthday, we revisit his band’s Jewish history that we first looked into in 2015.

The Who, the English rock group, is in the midst of yet another tour, one that they say may be their last — a claim they have been making since at least 1982. On this tour, the Who are mostly performing their best-known hits and fan favorites, including songs like “Pinball Wizard” from their rock opera, “Tommy.”

If the group’s visionary songwriter and guitarist Pete Townshend had had his way, “Tommy” — an allegory about a traumatized messiah — would not have been the band’s first rock opera. Following a visit to Caesarea, Israel in 1966 with his first wife, Karen Astley, and the subsequent outbreak of the Six-Day War, Townshend began work on “Rael,” a song cycle loosely based on Israel’s struggle to survive despite being massively outnumbered by its enemies. “Rael” — short for “Israel” — got sidetracked, partly due to the demands of the Who’s record company for faster delivery of more hit singles, and “Rael” was consigned to the shelf. The only song that has surfaced from that project is called “Rael” and appears on the late 1967 album, “The Who Sell Out.”

A deeper examination of who Pete Townshend is, which he provides in his aptly titled autobiography, “Who I Am,” reveals a man who, while not Jewish himself, has great empathy for the Jewish people and who sees the world very much through the eyes of a Jewish-influenced character.

The son of musicians with a tempestuous marriage, Townshend in his early years was shuffled around among relatives, friends and neighbors while his parents came and went, carrying on relationships outside of their marriage. In his autobiography, Townshend waxes nostalgic not for the comfort of his family, but for the Jewish world that protected him: “We shared our house with the Cass family, who lived upstairs and, like many of my parents’ closest friends, were Jewish. I remember noisy, joyous Passovers with a lot of Gefilte fish, chopped liver and the aroma of slow-roasting brisket.”

After a stint being raised by his grandmother, a period during which he was abused by her and the parade of boyfriends tramping in and out of her flat, he returned home to his parents. Again, his surroundings gave him the most security and happiness: “I was seven, and happy to be home again, back in the noisy flat with a toilet in the back yard and the delicious aroma of Jewish cooking from upstairs. It was all very reassuring.”

The Who evolved from a band called the Detours originally led by vocalist Roger Daltrey, who played guitar at the time. The band included bassist John Entwistle, a high school chum of Townshend’s. When the group’s lead guitarist quit the band, Entwistle recommended his friend. As Townshend tells it, the audition went something like this:

Daltrey: “Can you play “Hava Nagilah”?”

Townshend: “Yes.”

Daltrey: “You’re in. See you next Tuesday night.”

And so began The Who, a unique group of misfit musicians, none of whom played their instruments in conventional fashion. Drummer Keith Moon was no mere timekeeper; his was more of a textural, orchestral approach, and if you listen to the group’s early singles you’ll be surprised to hear drum solos where there would typically be guitar solos, which Townshend rarely played. Bassist John Entwistle filled the musical mid-range with soaring arpeggios and riffs, more like the work of a keyboardist than a bassist. And Townshend approached the guitar purely as a vehicle for sound and impact. “In rock ‘n’ roll the electric guitar was becoming the primary melodic instrument, performing the role of the saxophone in jazz and dance music, and the violin in Klezmer,” Townshend wrote.

In recent years, Townshend’s thoughts have once again turned back toward the concerns he expressed “Rael.” As he told an interviewer for Rolling Stone in 2006:

Last week, I was reading about this book that’s just come out. It’s about the Polish Jews who got out of concentration camps and went back to their homes, which had been taken over by Christians who assumed the Jews weren’t coming back. What happened was another wave of anti-Semitism in which dozens were slaughtered by Christians in Warsaw. The premise for it was that there was witchcraft going on. The Jews, of course, drank the blood of children. Been there, done that. F—king hell. And I asked myself, ‘Why am I so heated up about this f—-king story?’ But it’s because, as a kid, my best friend, Mick Leiber, was a Jew. We grew up in a community that was about a third Polish. We lived in a house that divided in two, and in the top part lived a Jewish family who were quite devout. Polish Jews were the kids I played with. They were my people. I remember saying to my mother, ‘Aren’t Polish people from Poland?’ And she said, ‘Yes, they were Britain’s first ally in the war.’ I’d say, ‘But they’re not like foreigners. They’re just like we are.’ And she said, “Yes, they’re just like we are.”

Unlike other fellow British rockers, most notably Roger Waters and Elvis Costello, who are vocal supporters of a cultural boycott of Israel, Townshend holds a pro-Israel stance, as he told the same Rolling Stone interviewer regarding the Who’s album, “Endless Wire,” a 10-song “mini-opera” about kids forming a rock band in the post-9/11 world.

And where are we today? We’re in the same anti-Semitic apologetic denial — it’s a dishrag of a policy. Trying to blame Israel for defending a country we created. And I’m not even Jewish! Jesus f—king Christ. And let’s start with him! Sweet Jesus. This album absolutely had to have several songs about Jesus the man, Muhammad the man, but not modern Christianity or Islam. They are both potentially anti-Semitic today. And I think the fact is that, when I was working on this album I just thought, ‘It’s f—king about time that I completed my story.’ At this time in my life, with nuclear threats coming from Iran and Korea, I am becoming so impatient with the ex-hippies all around me. I am suddenly thinking like an extreme reactionary, right-wing, warmongering… F—king hell, come inside my brain! The incredible numbers of dead in the last war make it clear that we can’t afford to wait to be hit again. That’s my opinion. That’s my story. Peace is something that has to be made. It doesn’t come from passivity.

Incidentally, “Endless Wire” also includes a song called “Trilby’s Piano,” a song about the hidden, forbidden love of a Jewish man named “Hymie,” sung by Townshend.

Apparently, Townshend’s immersion in all things Jewish has rubbed off on his longtime musical partner , Roger Daltrey, who, when asked a while back if the band would really stop touring, groaned like an old Jewish man, “We will always do shows for charity, when we can, because it’s of enormous value to people and Pete [Townshend] and I love to play. But we won’t do long, schlepping tours. It’s killing us.”

Seth Rogovoy frequently writes about the intersection of popular culture and Jewishness for the Forward. He has often been mistaken on the streets of major metropolitan areas for Pete Townshend.