What It’s Like To Play The First Cantor In Opera History

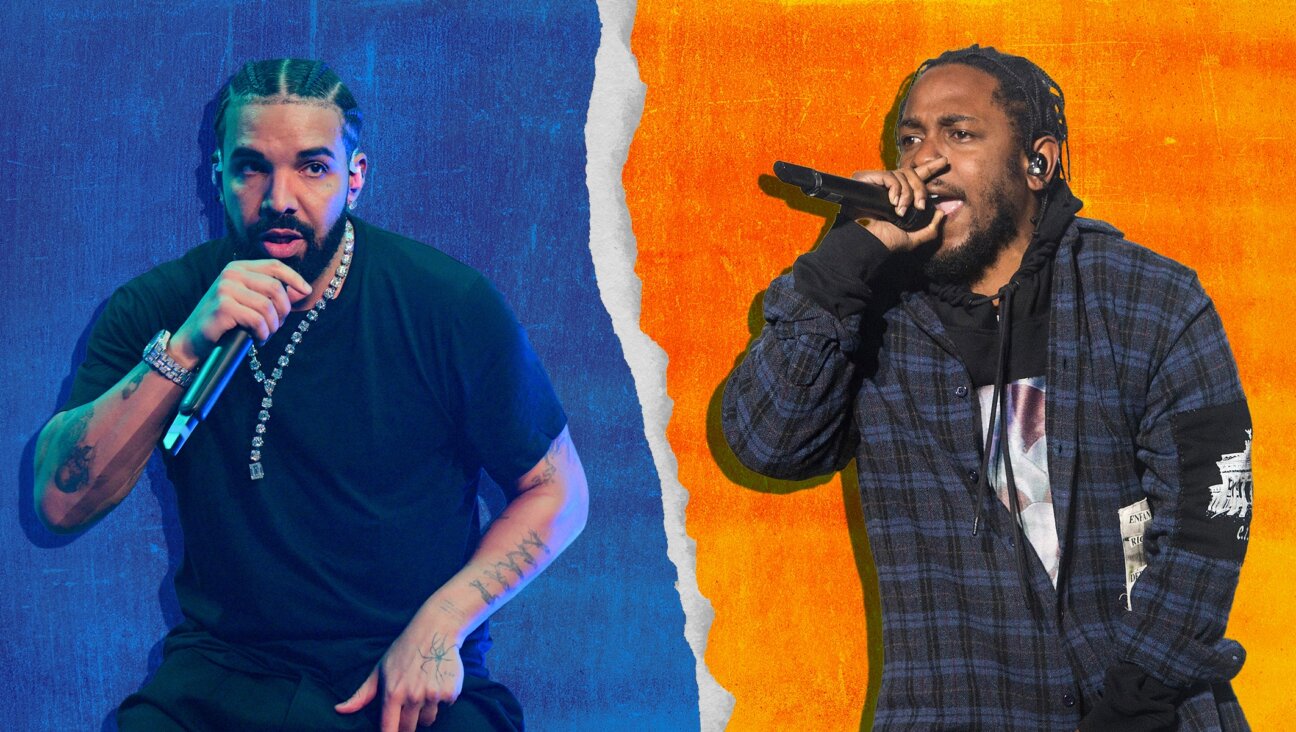

Netanel Hershtik in Na’ama Zisser’s “Mamzer Bastard.” Image by Stephen Cummiskey

Jews have always had a complicated relationship with opera. Ostracized in European society, Jewish composers and librettists had few chances to make professional headway; perhaps the most successful of them, Mozart collaborator Lorenzo da Ponte, converted to Christianity. The most influential late-Romantic opera composer, Richard Wagner, was a notorious anti-Semite. And prior to the mid-19th century — when Jewish composers began gain more prominence and, with it, use opera to tell Jewish stories — depictions of Jewish characters were often restricted to biblical stories.

That mixed history is part of what makes the debut of Na’ama Zisser’s new opera “Mamzer Bastard” remarkable. The opera, which premiered on June 14 and runs through June 17, is the culminating work of Zisser’s doctoral residency with London’s Royal Opera House. (Zisser’s residency was conducted in partnership with the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.) It’s radical for the opera to have a Yiddish word in its title; radical, as well, for it to be set among the New York Orthodox.

Most radical of all, though, might be the fact that the work has a part written for a cantor, purportedly the first opera to do so. Netanel Hershtik, cantor at New York’s Hampton Synagogue, originates that role in the Royal Opera House production. I spoke with Hershtik in advance of the premiere performance of “Mamzer Bastard;” the following interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Talya Zax: What’s your role in “Mamzer Bastard?”

Netanel Hershtik: The story in the opera is about someone who comes from the war to learn that his wife is re-married; he comes to America and finds his wife married with a kid named after him. She’s under the belief that he was dead. That father doesn’t want that son to be a mamzer, a bastard, because that’s the definition of anyone who is born to an illegitimate relationship, and so he tries to protect the kid by making sure he will get married. As soon as he gets married, it is know, the sages will not annul a wedding that is already in place. If he gets married, he’s ok.

Our story begins in 1977 in New York, in Brooklyn, the eve of Yoel’s wedding. He goes to the mikveh that night, and he’s very hesitant about his wedding. He’s lived all his life with the feeling that he’s not belonging to something, something is unresolved about him. He always feels a mysterious shadow, and so does his mother, Esther; she has the feeling that at certain points, landmarks in Yoel ’s life, she saw that shadow, she recognized that husband that she had before the war. She’s afraid that Yoel is a mamzer, too.

My role — I’m the neighbor. The neighbor is a cantor. Yoel ’s father, Menashe, is admiring that young cantor. The music of the cantorial style [makes] the only arias in the opera. Most of the [opera] is written in the modern music, it’s mostly recitatives, but the cantor comes up and gives a little peek [at] certain prayers or songs supposed to either accompany or touch the subject, or give encouragement, or give some spiritual sense in times of trouble. He’s not very central to the story, but musically speaking he’s very central. He’s the only one who has arias in this opera.

How did you come to be involved in this opera?

Na’ama Zisser is from Israel originally, [she] now lives in London. The Royal Opera House commissioned her to write a new opera. She writes in a very modern style, and she always wanted to do something with cantorial music. Na’ama initially contacted me, and we met, and then I had an audition at the Metropolitan Opera, because the artistic director of the Royal Opera House wanted to meet me in person.

How would you describe the cantorial aspect of the music in “Mamzer Bastard?”

It’s just accompanied by the orchestra here at the opera. But the music itself is pretty much the same style. I was brought into this opera not because of my operatic skills, but because of my cantorial skills. They were looking for something authentic, that brings the synagogue into the opera stage.

How have you found working as a cantor in an opera to be different from working as a cantor in a more ordinary setting?

It’s amazing. I’ve never worked with a director. Never worked with acting. There’s also elements of sound and elements of live video art, while the opera is going on. It’s a very modern, active production. It’s all very new to me, but on the same hand, I’m the most accustomed with the music. I’m the 14th generation of cantors. I don’t know who ever counted 14 generations. But that’s the legend in my family.

You told me this is the first operatic role ever written specifically for a cantor. What does it mean to you to be the first to perform this role?

I think it’s a great honor. It’s not the first time [I’ve brought] that music to an audience that never heard cantorial music. Back in 2012, when I was involved with Charles Krauthammer, he has an organization called Pro Musica Hebraica, he and Robyn, his wife. They make concerts at the Kennedy Center celebrating Jewish work that never made it to the stage because of persecution. They brought me to the Kennedy Center to present an entire evening of cantorial liturgical music. There also I sing to people who never heard cantorial music. Or in a concert I’ve been doing for the last three years, in Berlin, I’m the first cantor to ever sing in the Berlin Philharmonic Hall. I just think it’s lovely. It’s a great feeling that you’re representing that music to the world.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO