How a Brooklyn-born Beatles fan named Elliot Steinberg became a rock ’n’ roll legend

In the 1970s, Elliot Easton joined a band called The Cars — and the rest is history

Elliot Easton performs at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Photo by Getty Images

Musicians, most of them, don’t retire. They may shift gears, they may play to different sized crowds than they did in their youth, but they don’t stop playing. For them, it’s like breathing, eating, sleeping. When you love what you do, why stop?

Elliot Easton, who turns 70 Dec. 18, is one of those guys.

The left-handed guitarist hit the heights more than 40 years ago with The Cars, just two years after exiting Berklee School of Music in Boston.

Easton joined forces with singer-guitarist Ric Ocasek and singer Ben Orr, after the two had shut down a rock band called Richard and the Rabbits and went out as an acoustic duo, Ocasek and Orr. Easton had seen Richard and the Rabbits and liked them. “I could picture how I could play guitar with these songs,” he thought.

He also saw Ocasek and Orr play at the Idler, a folk club in Cambridge, and was introduced to them by his roommate and their soundman. Easton then got an invite from Orr to come to his house and play with them.

“I went over,” Easton says over the phone from his California home, “and Ben was sitting in a chair with his arms crossed and he said ‘Play something amazing.’ When someone says something like that, you can hardly play at all, but after a while I relaxed and they liked my sound.”

In 1975, a new band was assembled: Cap’n Swing, and Maxanne Sartori, a DJ at Boston rock powerhouse WBCN-FM, started playing their demo tapes on air. They did a showcase gig for management representation at Max’s Kansas City in New York and though Easton says “we went home with our tails between our legs,” they got constructive criticism — “the songs were a little stretched out, long solos, a little too jammy and could be more concise pop songs, more commercial.”

By the end of 1976, with some personnel changes — keyboardist Greg Hawkes and drummer David Robinson came aboard — the group tightened up as it mutated into The Cars. Sartori played The Cars even more, and in short order they were signed by Eliot Roberts, a major player in the rock industry management world, and then to Elektra Records.

Robinson came up with the moniker. “We were searching around for a name,” says Easton, “and it was that time every band was The This or The That. What I thought was clever, maybe even brilliant, with The Cars was that it was short — just four letters — and you could print it really large on the marquee of a venue. We were kind of surprised no one had ever used it before. It’s so connected — cars, girls, rock ’n’ roll.”

The Cars released their eponymous debut album in 1978, a record packed with hit singles and could-have-been hit singles. It sold more than six million copies. They were new wave radio-friendly and those hits launched the band from Boston clubland to the world’s stages.

Ultimately — though there were later reunion gigs and one more album in 2011 — The Cars had a 12-year run, 1976-1988, during which they notched 13 Top 40 singles. Over the course of six albums, they went on to sell more than 23 million copies.

“It’s everything that guys like me dreamed of doing,” Easton says, of that ride.

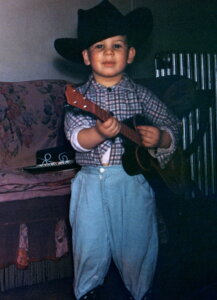

Easton was born Elliot Steinberg in Brooklyn and lived in Forest Hills, Queens, until he was 6. The family moved to Massapequa, Long Island, where he mostly grew up, graduating Massapequa High School in 1971. He changed his surname to Easton before The Cars released their first album.

“It was not a big deal,” he says. “It didn’t necessarily have anything to do with having a Jewish name. Lots of people change their name for showbiz and Easton is a little flashier. I felt it rolled off the tongue easily, it was a little Anglo sounding. Subconsciously, I was also thinking of Andrew Loog Oldham’s partner in the early days of the Rolling Stones, Eric Easton.”

His parents took no umbrage. “Not in the slightest,” Easton says. “They totally got it – my mother expected it because she was in the field already. She had her own radio show on Yiddish radio in New York in the late 30s and 40s and she was a Julliard-trained singer who sung Jewish music professionally. So, it was always in the house. Both my grandparents spoke Yiddish.

“I don’t go to temple every week for Sabbath but I identify as a Jew,” Easton told me. “Just the sensibility — the stressing of education and achievement, the food, the humor and the outlook on life which is colored by how I was brought up.”

Like his Cars bandmate Hawkes, Easton heard the Beatles as a kid and was hooked.“The thing that occurred to me the most is when you’re a kid coming up, learning to play guitar and wanting to be in a band, it’s your dream,” Easton said. “And so, I had achieved my childhood dream.”

That didn’t mean that everything automatically got brighter, he told me. “When you’re a kid,” he said. “You think if I could get a contract and just make a record it would fix everything in my life, and everything wasn’t fixed. I don’t mean that in a bad way, but I’d still go home at night and be alone with my own thoughts.”

“I was glad that the band was making it, but in some ways, there was a bit of an anti-climactic ‘Is that all there is?’ feeling. I was still me in the morning,” he continued.

When did he know The Cars had succeeded? “We would joke about it,” Easton said. “We’d ask our manager at different points, ‘Have we made it yet?’ It’s not like some bell rings and it’s like ‘OK, you’ve made it.’ It happens quickly but at the same time not all at once, so you have time to adjust and calibrate: OK, is this what my life is now?”

A theory has been floated that with the dominance of Ocasek and Orr in the Cars, Easton’s role and his guitar playing were underrated. “Well, I don’t know,” he says, with a laugh. “That’s what people say. I just try to do good work. I feel pretty rated. I was never marketed or branded as a guitar hero and part of that was management and Ric. They didn’t want me to do that.” (Easton turned down some guest spots on other artists’ albums that might have done a better job of showcasing his talents.)

“If people think I’m underrated in some ways,” he adds, “maybe it’s just because what I do is a little more subtle than the average lead guitarist. It’s not in your face, it’s more thoughtful, composed stuff and it just doesn’t hit you over the head like a heavy rock solo.”

In 2018, The Cars got that proverbial cherry on the rock cake, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nomination, bringing the long-gone band together to play one more time, albeit without its main singer, Orr, who died in 2000. Weezer’s Scott Shriner assumed Orr’s position.

“I think it’s cool,” Easton said of the induction. “Whatever the good and bad is about the whole thing, it is the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and it’s an honor to be inducted.”

Easton’s post-Cars resume includes 11 years with Creedence Clearwater Revisited (playing with the two guys not named John Fogerty in Creedence Clearwater Revival) and nine years with the garage-pop band Empty Hearts. There was even a brief go-round as the New Cars, with Hawkes and Todd Rundgren.

Easton lives in the San Fernando Valley with his second wife of 12 years, Jill Glass Easton. If you’re in the area, you might spot him playing Chicago blues at the Write-off Room with Barry Goldberg’s Groove Summit. Next year, he goes on the road — and in February on a Rock Legends cruise aboard Royal Caribbean’s Independence of the Seas — with the Immediate Family. He’s stepping in for his friend Waddy Wachtel, who will be playing in Stevie Nicks’ band on tour.

As to playing smaller venues and to smaller audiences, Easton told me, “It doesn’t really matter. With The Cars I always adapted, but what I’m really enjoying is being able to play some of the music that is more akin to what my actual roots are: blues, country and American rock ’n’ roll.”

He’s also got a new behind-the-scenes gig working as a music supervisor for J.J. Abrams, who’s doing an eight-episode series for Netflix. “I can’t say anything about that,” said Easton, “but if you know J.J., you know he’s great. And he was a Cars fan.”