For a Jewish jazz great, a 100th birthday is a time for a celebration and a new album

Vibraphone pioneer Terry Gibbs was born Julius Herbert Gubenko in Brooklyn, 1924

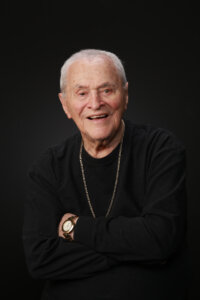

Terry Gibbs at the keyboard. Courtesy of Terry and Gerry Gibbs

This article was prepared in collaboration with CapitalBop,

Making it to your 100th birthday would be an impressive enough accomplishment for any musician, but for legendary vibraphonist and bebop pioneer Terry Gibbs, it’s also an opportunity to promote a new release from his archives. The musician’s 1959: Vol 7: ‘The Lost Tapes” by Terry Gibbs’ Dream Band will be released on Oct. 13, the same day as his centenary.

“One day, maybe two months ago, I had nothing to do,” Gibbs told me,”and I’m going through things and come across a tape that says ‘Jazz Party 1959.’ I looked at it and thought, ‘I don’t remember that at all,’ so I put on, and it was the original Dream Band of 1959 — and the band sounded amazing. It sounds like it was recorded yesterday. Every song hits you in the head — it’s like you’re sitting in the front row. So this cockamamie thing happened — I’m producing an album when I’m almost 100 years old; I should be sitting in the house just eating gefilte fish!”

Julius Herbert Gubenko, better known as Terry Gibbs, actually retired from performing at 92. But he’s still actively promoting his career and has lost absolutely none of the razor-sharp wit for which he is almost as well-known as he is for his musical virtuosity. When this interviewer erroneously speculated that the vibraphonist might be the last surviving musician who played with Bird, without missing a beat, Gibbs set him straight: “No! Roy Haynes! He’s a baby – a full six months younger than me.”

Julius was born in Brooklyn on Oct. 13, 1924. His father, Abe Gubenko, was a violinist and led “Abe Gubenko and his Radio Novelty Orchestra.” While Julius was still in his single digits, he played drums, and later, xylophone, klezmer music, ballroom dance tunes, and other popular music of the day for the band. When he was 12, he won the Major Bowes Amateur Hour Contest, the 1930’s radio equivalent of America’s Got Talent.

As a teenager, he took the name “Terry,” after his favorite boxer, Terry Young (Young Julius was a bit of an amateur pugilist himself). Bandleader and vocalist Judy Kayne couldn’t handle the complexity of Julius’ given surname and called him Gibbs instead.

Gibbs’ burgeoning jazz career was interrupted in 1943 when he was drafted into the Army where he played drums with an orchestra.

“When I got out of the service (in 1944), I was about 22, and Tiny Kahn took me to hear Bird and Diz,” Gibbs said. “I found Shangri-La. That’s what I’d been looking for all my life. I had all this technique and didn’t know what to do with it, ‘cause my idols had been Roy Eldrige and Lester Young and they played simple and lyrical. And when I heard Bird and Diz, that threw me for a curve.”

In those post-war years, he worked with many of the great big band leaders, including Chubby Jackson, Woody Herman, Buddy Rich, and Benny Goodman, the latter of whom he (not entirely) affectionately dubs, “El Foggo” in his 2003 autobiography, Good Vibes. Before long, Gibbs found himself leading his own combos, frequently appearing at Birdland where he played alongside jazz greats, including Washington DC’s own Duke Ellington. I was always the third-billed attraction, but I got to work opposite all the heavies!” Gibbs said, recalling that Ellington was the “loosest” of all the bandleaders he saw.

“He was even looser than my band. I’ll never forget,” Gibbs said. “Usually at Birdland, one band follows immediately after the other. My band would finish playing and two or three minutes would go by and then Duke would sit down at the piano and start playing there by himself. Maybe after a minute or two a trombone player would wander out and join him. Then a sax player. And everybody would finally sit down, but Johnny Hodges wouldn’t sit down until everyone else had sat down.”

In the mid-1950’s, Gibbs’ quartet featured one of a series of astounding musical discoveries made by Gibbs over the years – the Detroit-born pianist and vibraphonist Terry Pollard. “She was way ahead of her time. Terry Pollard had that ‘dirt’ when she played. She played bebop and she was as good a vibes player as practically anybody.” The two appeared together on a 1956 episode of The Tonight Show, hosted by Steve Allen.

Did Gibbs incur pushback for featuring a Black woman so prominently in his band? “I didn’t care,” he said. “But those boys down south did. No one wanted to beat her up – they wanted to beat me up!”

Gibbs said that one club owner offered to book him for 60 dates a year if he dropped Pollard from his act. ‘I’ll get rid of her if you get rid of your fat wife.’” Gibbs told him.

Another one of his discoveries was the pianist Alice McLeod, later to be better known by her married name of Alice Coltrane. She made her recording debut on Gibbs’ 1963 album Jewish Melodies in Jazztime, produced by Quincy Jones who, according to Gibbs, showed up the first session wearing a tallit and yarmulke to show he was enthusiastically behind the project.

“She could sound like Bud Powell!,” Gibbs said about McLeod’s audition for him. “She was with me for a whole year. After about ten months, we worked a job opposite John Coltrane. I knew John ‘cause I had worked opposite Miles when he had John. There used to be a table at Birdland all the way to the back and to the right, which faces the back of the band, so that would be the musicians’ table. John was going through his thing of really screeching a lot – it wasn’t my thing. But Alice loved it. So she’d sit there and listen every night. After a few days, I introduced her to John – she was very shy – but they started to get close. A week or two later, I get a call from my agent saying he booked me into the London House in Chicago. Then, about a week before the gig, Alice comes to me and says John wants her to go to Sweden with him and get married. If it had been anyone else, I would’ve called my ‘attorney Bernie’ and sued her, but how do you stop someone in love? She was such a sweetheart of a person – we remained great friends.”

One of Gibbs’ most obvious musical descendants is Chuck Redd, who has made a name for himself around the globe playing both vibes and drums. “Terry has been an inspiration to me since the first time I heard one of the Dream Band albums when I was about 18,” Redd told me. “His playing was so swinging and exciting and the band is one of the greatest ever. It’s remarkable to think that Terry has been one of the most important vibes players since the early years of the instrument’s prominence.”

““His creative energy is unstoppable,” Redd told me. “Speaking with this man who is a century old is like interacting with a 30 year old! He’s quick witted, he’s interested in what everyone is doing, he loves to discuss the nuances of music and life and he’s hilarious! I love Terry Gibbs.”

Vibraphonist Warren Wolf offers similarly effusive praise. “He’s such a gentleman. He’s one of the most talented guys. He plays great piano, bass, and drums, as well as vibes,” Wolf said, “ I learned about him watching a YouTube video – this classical guy playing marimba with a symphony. And I said, ‘I don’t believe it – that’s something I used to do. But he’s doing it 20 times better than I did!’ So I said I gotta find out about him. So finally I got his number and called him and told him how great he sounded. And about a year later he came out to my house and visited me. And he was so respectful it was ridiculous.”

“As a vibraphonist, he’s at the very top of the instrument chain,” Wolf added. “He’s a pioneer for the instrument. I think that people don’t talk about him as much as they really should. When it comes to that style of playing, people immediately go to Lionel Hampton, but Terry Gibbs was right there among the greats. He was a superstar for the instrument back in the day. But the thing about him – he’s a living legend who’s still with us right now who’s played with everybody. And if he didn’t play with them, he hung out with them.”

Terry Gibbs’ latest release is 1959: Vol 7: ‘The Lost Tapes” by Terry Gibbs’ Dream Band.