In 1964, when he was just 23, Bob Dylan wrote the prophetic anthem that encapsulates Trump’s America

Decrying a world characterized by materialism, violence and blind conformity, Dylan echoed the warnings of King Solomon

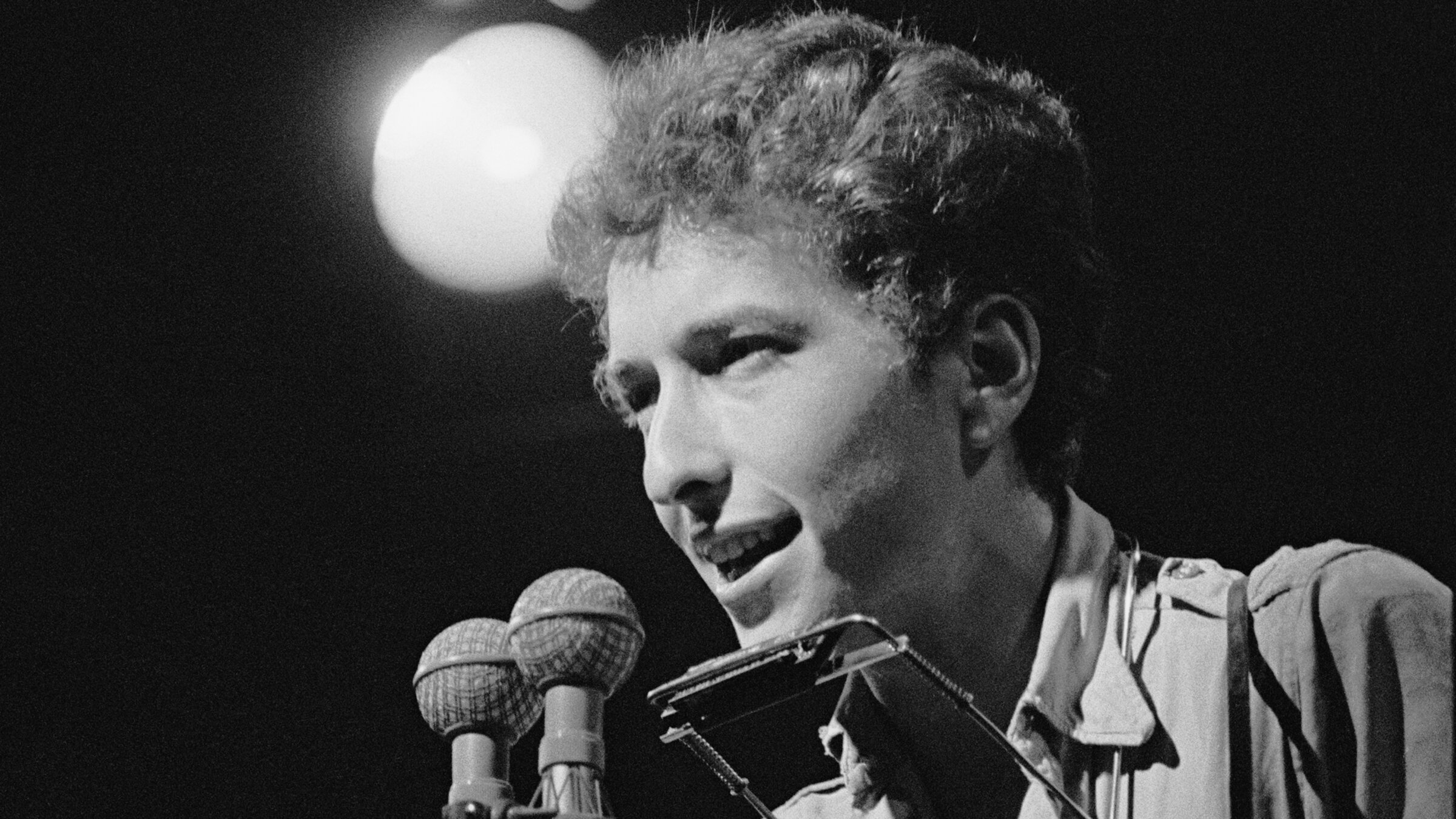

Bob Dylan, circa 1963. Photo by Getty Images

In a much-overused construction, Bob Dylan is often referred to as “the voice of a generation.” Dylan won that epithet — which he never liked and often repudiated — with his topical songs of the early 1960s, many of which addressed the burgeoning activism of the time. His earliest songs spoke to the Civil Rights Movement as well as antiwar, antipoverty and antinuclear protests. After his short-lived period of writing topical protest songs, Dylan shifted to addressing more timeless concerns in the more poetic, sometimes abstract language found in mid-1960s songs such as “Chimes of Freedom,” “Gates of Eden,” and “Desolation Row,” songs that became full-throated expressions of the counterculture.

The more things change, the more they stay the same, and part of the genius of Dylan is that these songs, while reflecting the time in which they were originally written and sung, are also timeless. This is presumably in part why Dylan is the only songwriter ever to win a Nobel Prize for Literature. When we listen to songs like the aforementioned, as well as numbers including “Highway 61 Revisited,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” and “All Along the Watchtower,” they often capture whatever moment we are in. They transcend their immediacy through language and imagery that, like most poetry, resonates with truths that speak above and beyond time, and like the words of the Biblical prophets, which continue to resonate with millions of modern-day readers.

With well over 600 songs in Dylan’s catalog, it is never difficult to find lines or verses that speak to whatever defines the moment. Take 1967’s “Too Much of Nothing,” in which Dylan sings, “Too much of nothing can make a man abuse a king / He can walk the streets and boast like most / But he wouldn’t know a thing.” Those lines echo through the decades, as do the following: “Too much of nothing can turn a man into a liar — when there’s too much of nothing it just makes a fella mean.” Remind you of anyone?

Around the same time, Dylan wrote in another song, “I pity the poor immigrant who wishes he would’ve stayed home.” Note that this was in an era when immigration was not anywhere near the heated topic of political conversation that it is today. “I pity the poor immigrant whose strength is spent in vain / Whose heaven is like Ironsides / Whose tears are like rain,” Dylan continued, borrowing imagery from the Book of Leviticus, chapter 26. On that same album, Dylan sang in “All Along the Watchtower” — which borrows its central imagery from the Book of Isaiah, chapter 21 — “‘There must be some way out of here,’ said the joker to the thief / ‘There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief’,” expressing a sentiment many of us feel these days after perusing the news.

One continues to find such resonant phrases in Dylan’s writing throughout the 1970s and beyond. “Socialism, hypnotism, patriotism, materialism / Fools making laws for the breaking of jaws / And the sound of the keys as they clink / But there’s no time to think,” Dylan sang in “No Time to Think” on his 1978 album, Street Legal. In “Pay in Blood,” a hard-rocking number from the 2012 album, Tempest, Dylan sings, “Our nation must be saved and freed / You been accused of murder, how do you plead?”

When seeking solace or wisdom about this very moment, I often return to “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” a song Dylan wrote more than 60 years ago — in summer 1964, at the ripe old age of 23 — and which he recorded in January 1965 for the album Bringing It All Back Home, which was released the following April. Part of the prophetic brilliance of “It’s Alright Ma” lies in its timelessness and universality. The song decrying materialism, violence, blind conformity, and political hypocrisy is pretty much always relevant (for better or worse), but sometimes it is more relevant than other times. And now is one of those times.

The very first line of the song offers a hint at some of its concerns. “Darkness at the break of noon,” intones Dylan, alluding to Arthur Koestler’s best-known novel from 1940, the dystopian Darkness at Noon, which portrayed life under a totalitarian dictatorship. Dylan continues with imagery of a world turned upside down, where “Shadows even the silver spoon, the handmade blade, the child’s balloon eclipses both the sun and moon.” The very laws of astrophysics are turned on their head.

Dylan goes on to sing about “Pointed threats, they bluff with scorn” and “disillusioned words like bullets bark,” as if forecasting the horror show to which we are now witness, whereby on social media, in speeches, and in interviews, the president of the United States daily unleashes a torrent of invective. Dylan even anticipates the president’s fondness for that most precious of metal — in the form of a Gold Card enabling multimillionaires to buy their way onto these shores as legal immigrants; or a proposed “Gold Dome” patterned alongside Israel’s Iron Dome, an incredibly efficient multi-mission mobile air defense system; or the self-declared king’s favorite chair: his golden throne — when he sings, “From the fool’s gold mouthpiece the hollow horn plays wasted words….” Anyone who sat through the president’s nearly two-hour long address before Congress (on March 4, 2025) can appreciate that description.

Dylan continues: “While preachers preach of evil fates / Teachers teach that knowledge waits / Can lead to hundred-dollar plates” pretty much summarizing the current administration’s philosophy of education. Edwin Starr’s valuation of war is the equivalent of the White House’s valuation of schooling: “What is it good for? Absolutely nothing.”

Dylan has long favored “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” in his concert performances. It was a staple of his 1974 “comeback tour” with The Band, marking his first series of concerts since his first “retirement” in 1966. At those early 1974 concerts, audiences responded to the line “even the president of the United States sometimes must have to stand naked” with a huge round of applause, as the tour took place when then-President Richard Nixon slowly began twisting in the wind of the Watergate scandal. Today’s audiences, on the other hand, may not even want to imagine what a sight that must be.

There is a strong connection between “It’s Alright Ma” and the book of Kohelet, more commonly referred to as Ecclesiastes. The book is sometimes seen as an ode to futility, a theme Dylan picks up for his song. Kohelet begins, “Futility of futilities! All is futile!” In Kohelet, King Solomon — the purported author — explains what he set out to accomplish: “I applied my mind to study and probe by wisdom all that happens beneath the sky … I observed all the deeds beneath the sun, and behold, all is futile” (Kohelet 1:17).

Dylan renders this same sentiment – including references to the sky, the sun, and futility (“There is no sense in trying”) — in his own poetry:

Darkness at the break of noon

Shadows even the silver spoon

The handmade blade, the child’s balloon

Eclipses both the sun and moon

To understand you know too soon

There is no sense in trying.

“It’s Alright, Ma” paints a world spiraling into oblivion; hence, the circular guitar riff that punctuates the end of each stanza. Dylan’s target here is nothing less than modern society in all its godless, faithless materialism. Dylan goes on at length in a nightmarish vision of a world where children are sold “toy guns that spark” and “flesh-colored Christs that glow in the dark,” where, in a litany of phrases that collectively could make up its own chapter of Proverbs, he sings about “advertising signs that con you into thinking you’re the one / That can do what’s never been done,” where “money doesn’t talk, it swears,” and where, finally, “all is phony.” Dylan ponders his place in such a world when he notes that if his “thought-dreams could be seen / They’d probably put [his] head in a guillotine.”

“All words are wearying,” complains Solomon in Kohelet, and Dylan echoes him, singing of words that are “wasted” and “disillusioned.” Dylan speaks of “them that must obey authority / That they do not respect in any degree / Who despise their jobs, their destinies,” echoing Solomon, who writes, “What profit does man have for all his labor which he toils beneath the sun?” In a fit of cynical optimism, Solomon reminds us that “the living know that they will die, but the dead know nothing at all,” which Dylan renders as “For them that think death’s honesty / Won’t fall upon them naturally / Life sometimes / Must get lonely.” In his liner notes for Bringing It All Back Home, Dylan offers a couple of specific examples of Solomon’s generalized lament that “there is nothing new under the sun” when he writes, “the Great books’ve been written, the Great sayings have all been said.”

And what of Dylan’s “masters [who] make the rules / For the wise men and the fools”? Solomon said to himself:

The fate of the fool will befall me also; to what advantage, then, have I become wise? But I came to the conclusion that this, too, was futility, because the wise man and the fool are both forgotten. The wise man dies, just like the fool. — Kohelet 2:15-16

Or, as Dylan puts it, “It’s alright ma, it’s life, and life only.”