‘Kavalier & Clay’ could be a Jewish-American ‘Ring Cycle’ — what would Richard Wagner think of it?

The adaptation of Michael Chabon’s novel traces a uniquely American mythology

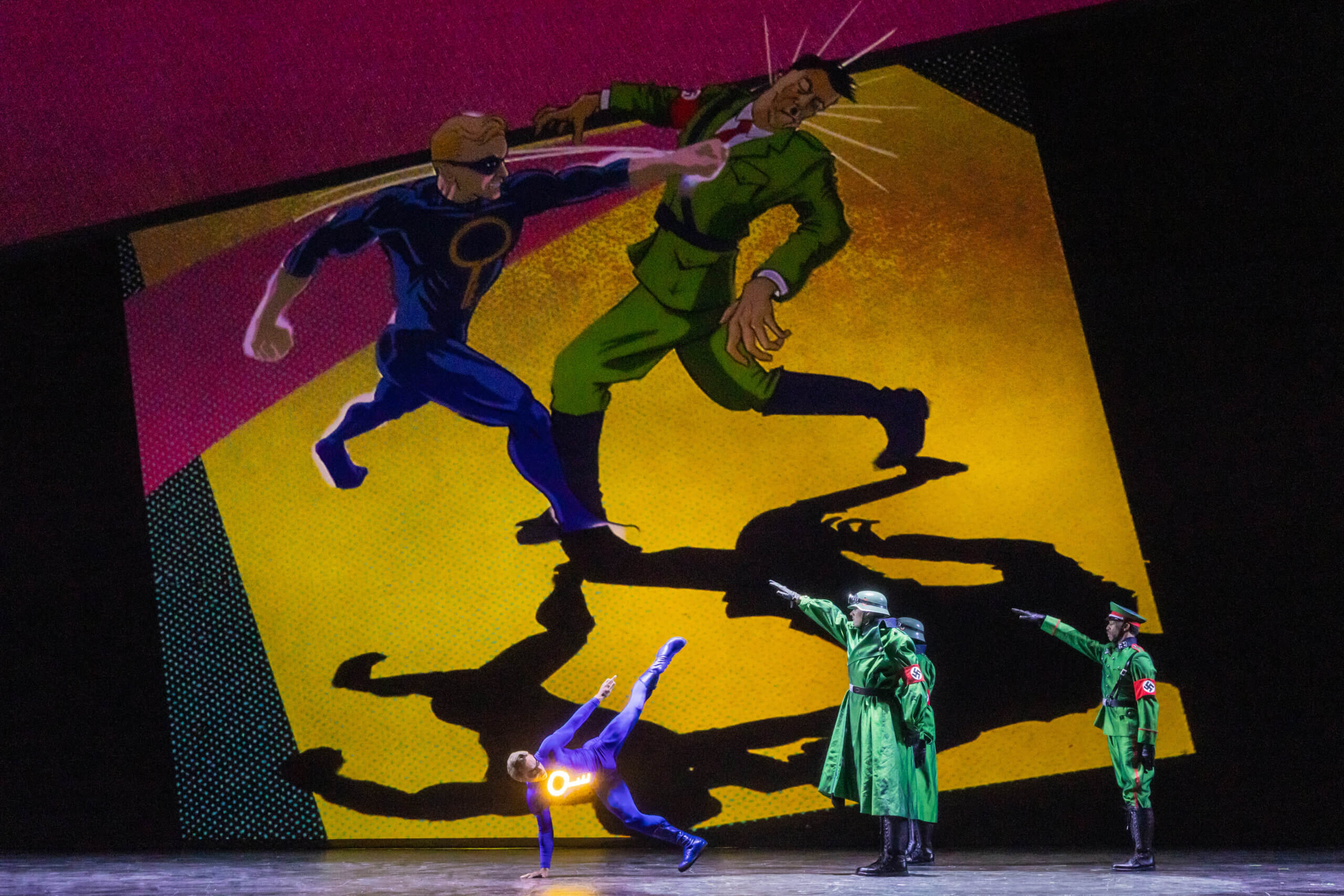

Andrzej Filończyk as Joe Kavalier and Lauren Snouffer as Sarah in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. Photo by Evan Zimmerman

It begins in the old world.

A fog rolls in. Statues of saints on the bridge over the Moldau have their backs to us. Facing front is a young man in a straitjacket, planning his escape. Heralding his theatrics are horn blasts that can only be called Wagnerian.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, now at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, was always fated to confront Richard Wagner. How it chooses to engage gives the composer a wry kind of credit, while also proving his limitations.

Based on Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning epic about two Jewish cousins and their fight with fascism through superhero comics, the opera is a work of mythology that wonders at the meaning of a national hero. Operatic material involving magic, epic battles and national identity can’t ignore Wagner’s Ring Cycle. And so, composer Mason Bates writes in his program notes, the sound of 1939 Prague includes “Wagner tubas (for the Nazis, duh).”

This swipe at Wagner recalled for me the old sorcerer’s remarks on Jews and music, first published pseudonymously in the 1850 essay “Das Judenthum in der Musik”: “We might hold the Jew adapted for every sphere of art, excepting that whose basis lies in Song.”

Wagner reasoned that the Jew was not of Europe, and so the continent’s art and civilization were but a “foreign tongue” to which he contributed little. When the Jew takes up music in the continental tradition, “his adaptations needs must seem to us outlandish, odd, indifferent, cold, unnatural and awry.”

The Met’s season opener, drawing from Jewish liturgy, popular music and a Gesamtkunstwerk of comic book elements, serves as a rejoinder in feeling so native to the venue.

Blaring back at the writer of these words, Kavalier & Clay uses a Wagnerian mode to signify the cold oppressiveness where this ideology led. Bates, working with a libretto by Gene Scheer and direction by Bartlett Sher, presents these sounds as a counterpoint to the new world of the United States. The bound figure we see as the curtain rises is Josef Kavalier (baritone Andrzej Filończyk), who makes his way in a coffin by train and then by boat, to safety in New York, warm with promise and novel instrumentation.

Desperate to rescue his family from the Nazis, Joe and his cousin Sam Clay (tenor Miles Mykkanen) create an American Übermensch, in vibrant tableaux scored vaguely like the prelude to Das Rheingold fed through synthesizers.

Chabon’s brilliance, in the cousins’ first creation, the Escapist, was to juice the anodyne, New Deal virtues of Superman into an explicit avatar of emancipation, giving voice to what truth, justice and the American way may actually mean.

As Sam puts it in a mesmerized aria, lifted from the novel, “to all those who toil in the bonds of slavery and the shackles of oppression, he offers liberation.”

In the world of the opera, as in the book, Superman still exists, but the Escapist beats Captain America to the famed punch to Hitler’s jaw. Joe Kavalier, a Jewish refugee inspired by his own miraculous escape and the marvels of Harry Houdini, draws the Escapist with straw-colored hair, as Jack Kirby did Steve Rogers.

Sam Klayman, going professionally as Clay, American-born, knows enough to name their hero’s secret identity Tom Mayflower, giving him a connection to a Puritan pedigree and a refugee founding myth. (Sam later falls for the man who voices him on the radio, Tracy Bacon, played by Edward Nelson, whose name is not incidentally treyf.)

Wagner would no doubt damn the results as another Jewish appropriation striking a false note. In his epics — and his own hero, Siegfried — he asserted certain blood and soil birthrights, elemental legends of gods and men underpinning an entire civilization and Volksgeist. As Kavalier & Clay moves away from that realm, another paradigm takes shape: that Jews may not only belong, but make the myths themselves.

In the U.S., there is no one ur-myth beyond that often false promise of sanctuary etched near the Statue of Liberty. With almost everyone an immigrant, the cliché of the melting pot holds, and assimilation adds to the brew. This mix doesn’t register as alien, as Wagner asserted Jewish speech did, but like the voice of a society whose native tongue is polyglot.

Bates’ touchstones include George Gershwin and Leonard Bernstein, who while similarly faulted for failing to faithfully capture the music of Black and Latin origin, helped invent a soundtrack for the United States. Within Chabon’s legend of how Jews created a secular, American pantheon, these musical influences tell not just a superhero origin story, but that of the arc of Jewish American life in the 20th century.

As Sam and Joe find their rhythm making comics, Bates’ score turns to Tin Pan Alley and big band. This leads to jarring results when the action, sometimes accomplished via ingenious moving split panels by scenic designer Jenny Melville, jumps to Europe. For instance: we see a horn-accompanied murder by Gestapo right before a comic sequence where the cousins’ mounting success is celebrated in Times Square with their boss Sheldon Anapol (Patrick Carfizzi) and his chattering steno pool.

The breadth of Bates’ soundscapes are impressive, particularly in sequences where Mark Grimmer’s projections bring life to Joe’s drawings, first glimpsed in hasty outlines, and later fully animated. The opera is never as thrilling as when it vibrates with the cousins’ ideations. For that reason the second act, in which they’re apart, feels largely inert as Joe goes off to the front and Sam makes an unconventional family in the suburbs with his cousin’s lover, Rosa Saks (Sun-Ly Pierce).

Just before the Escapist is born, a glowing gold key on his spandex-straining pecs, we get a vision of what Joe left behind.

A chorus of prisoners in a cattle car to Auschwitz sing a song in Hebrew, in the mode of liturgical music Wagner dubbed a “sense-and-sound-confounding gurgle, yodel and cackle.”

While a setting of the Shema or Kaddish would be the obvious choice, Bates and Scheer instead have them sing a selection of Ani Ma’amin that avows faith in the coming of the messiah.

In the superhero, an American messiah arrived. Wagner would have hated him.