How A Teenage ‘Shabbos Goy’ Stowed Away On America’s First Antarctic Exploration

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Teenagers dream about running away. They always have; they likely always will; often, when they do, the results are decidedly weird. (See: Haight-Ashbury circa the 1960s.)

But there’s packing a knapsack and setting out for the Summer of Love, and then there’s swimming across a major river intending to hitch a ride on a boat to Antarctica. In August of 1928, Billy Gawronski, the son of Polish Catholic immigrants, a Yiddish-speaking former “Shabbos goy” and a library-frequenting fan of adventure tales, did just that.

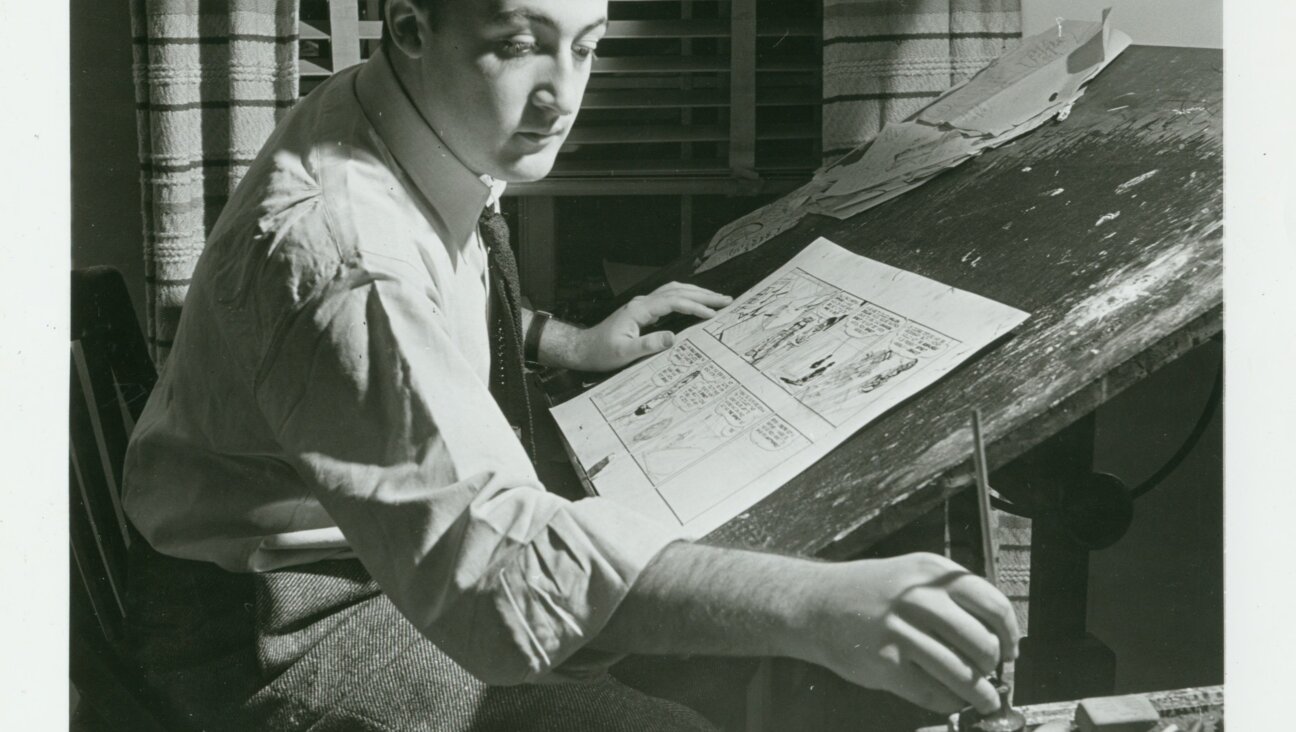

Billy Gawronski, pictured upon his return from Antarctica in 1930. Image by Gizela Gawronski/Jósef Piłsudski Institute of America

The night before Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd’s first Antarctic expedition departed from Hoboken, New Jersey, Gawronski swam across the Hudson River at 4 a.m., pulled himself aboard the ship and hid in what was effectively a crawl space. (He wasn’t alone; two other young men had executed similar maneuvers.)

It didn’t work; Gawronski was quickly caught and sent back to his parents. Yet two weeks later, he tried the same trick, twice boarding and twice being thrown off the Eleanor Bolling, an expedition ship that followed the flagship City of New York. (The expedition included four ships, which carried, alongside more conventional equipment, a disassembled early aircraft designed to resist extreme weather. Byrd intended to fly the craft over the South Pole.) Not content with having twice failed to stow away, he ran away a third time and hitchhiked by car to Norfolk, Virginia, where the Bolling would be making a stop. Improbably, Byrd offered him a job on the expedition. And they were off.

That story, sensational in its time and long forgotten, receives new life in Forward contributor Laurie Gwen Shapiro’s “The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica,” her first nonfiction book. I spoke with Shapiro about the book, her own Antarctic adventure and the first Antarctic Passover Seder. (It happened, extremely far from Jerusalem, in 1929.) Read an edited version of that conversation, below.

Talya Zax: How did this story come your way?

Laurie Gwen Shapiro: I’ve had two careers. I’m a documentary maker and had a career, when I was younger, as a novelist. I wrote the first Jewish chick-lit novel, “The Matzo Ball Heiress,” so Antarctica is not my particular turf. [But] I wanted to write more of the kind of books that I actually read. I was looking to write a book that unfolded like a novel but was deeply researched, like a documentary.

I’d started to write a small piece on a church on the Lower East Side, St. Stanislaus Parish, and their Sunday school, [and] I came across the mention of some teen stowaway who had a parade of 500 people marching for him upon [his] return. I sort of just forgot about my other article. I made a crazy Excel chart and I called up and down the Eastern Seaboard and said ‘Are you possibly a descendant of a kid who swam across the Hudson River and stowed away?’ Eventually this one woman said ‘That was my husband.’ And I knew right then, especially when she said ‘I have everything, come see me,’ I knew I had a book.

What was your process like from that point?

What she had, in addition to all sorts of photographs and things, was scrapbooks. One that he had kept before he stowed away, and one that his mother had kept after she recovered from her shock. Those scrapbooks included articles that I would have never found if I spent years researching.

His first marriage was not good. He had two sons and they were supposedly dead. I realized that [one] son was alive and in jail, so I had two living sources. Everything that he said really checked out.

Laurie Gwen Shapiro. Image by Franco Vogt

I decided that I needed to go to Antarctica as well, to leave the way the old explorers went, from the bottom of New Zealand, over very rough waters, into the Ross Sea. One of the greatest moments that I’ve had is when the Old Antarctic Explorer’s Club had told me that this [book] is very factually correct.

This book comes at a point when many people are reevaluating what it means to be American. What does this story mean to you, in context of that new questioning?

I feel like this is a part of American history that was lost — a little sliver, we’re not talking about Abraham Lincoln here. Admiral Byrd, at one point, in 1926, he was the most famous man in America. 1927, he lost to [Charles] Lindbergh. The two of them were neck-and-neck.

I think what’s interesting is the notion of American exceptionalism. This was America’s first expedition; this was America’s explorer; and everyone was behind him, except for a few people making raggy comments in The New Yorker, like E.B. White. This was the first time anyone was really going to fly over Antarctica. Imagine flying over the Grand Canyon for the first time! A lot of the popular magazines, including science magazines, had theories that maybe there were lost peoples, maybe there were dinosaurs. This was the equivalent of going to the moon, and an all-American guy was leading it.

What’s interesting about Billy is he’s not coming from the classes that some of the other people on this trip are. Everybody was volunteering to go on this trip, including the most elite families. Even if his father had let him apply, out of 70,000 [applicants], there’s not a chance in hell that anyone like him would have been considered.

This book not only tells the story of the first Byrd expedition but really of that transition of American from 1920s into this new shock [of the Depression]. The idea that in a couple of years the country, the nation could be in turmoil, I feel that unrest today, and I didn’t feel that kind of unrest five years ago.

What are some of the most interesting responses you’ve gotten from readers?

A gentleman reached out to me and said his father, who is 93, was a first officer under Commander Gawronski in WWII.

[Gawronski] becomes a very decorated WWII sea captain. [In the Depression] the only work available to him was back in the coal rooms down in the ships. In the 1930s, the wealthier Jews started to flee Germany, and he was working for the SS Manhattan. Because of his ability to talk to the passengers — and they were shocked that he was not Jewish — the passengers started telling the officers that this man was officer material. He was put on a fast track through the merchant marine, not through the Navy. He was one of the youngest sea captains in World War II.

His wife told me that one of his greatest regrets was hearing about the ship that came to New York, full of Jews, that had to be returned. That haunted him tremendously.

Where are you searching out ideas for your next book?

I feel like my niche is the crazy true story. My dad is 97, and he’s moved in with my family. I think having been around my father — having a comfort with older voices, and not dismissing him — has taught me how to not dismiss other sources. Some of the great stories that I’ve stumped upon have been [from] octogenarians and nonogenarians [who] are ignored.