A century before Trump targeted Somalis, Jews faced the politics of blame

In 1908, New York’s police commissioner falsely accused Jews of committing half the city’s crime

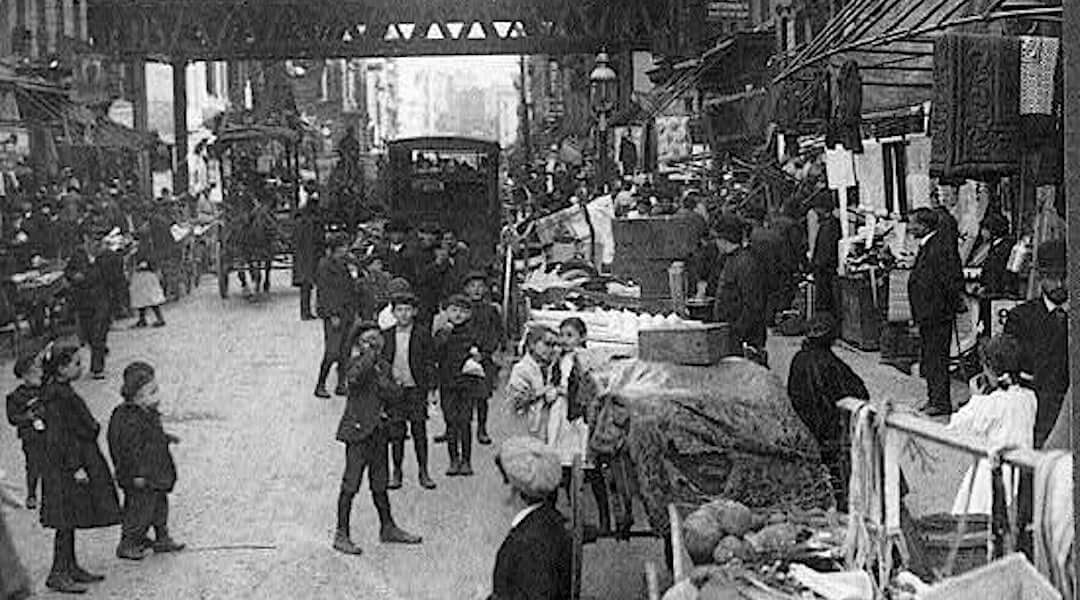

The crowded “Hebrew district” of New York’s Lower East Side, c. 1907. Photo by Underwood & Underwood/Library of Congress

(JTA) — As President Donald Trump ramped up his rhetoric against Somali immigrants in Minnesota and ordered a surge in immigration enforcement because Somalis took part in a social-service fraud scheme, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey pushed back.

“’When a fraud takes place, when a crime takes place, you investigate it, you prosecute it, you charge it. You arrest the person that did the fraud or the crime, you put him in jail as an individual,” Frey told NPR. “You get held accountable as an individual. That’s how this works in America.

“You do not, however, hold an entire community accountable for the crimes of one.”

Frey’s remarks were echoed by other state and national figures. “We do not blame the lawlessness of an individual on a whole community,” said Rep. Ilhan Omar, the Minnesota Democrat, who herself immigrated from Somalia to the United States as a child.

Frey, who is Jewish, didn’t mention his own background in standing up for Somalis, a community of whom Trump has said, “And they contribute nothing. The welfare is like 88%. They contribute nothing. I don’t want them in our country. I’ll be honest with you.”

But had Frey turned to Jewish history, he may well have cited another instance in which a powerful political figure blamed an immigrant community for the crimes of a few, and an ethnic group was targeted by nativists who pinned the country’s ills on immigrants.

Frey might have reached back to 1908, when New York City Police Commissioner Theodore A. Bingham leveled what at the time was the most explicit, highest profile accusation of Jewish criminality made by a major American official since Gen. Ulysses Grant expelled all Jews from his military district to combat allegations of cotton smuggling and corruption.

That year, in an article in the North American Review, Bingham claimed Jews accounted for half of New York’s crimes, especially picking pockets, fencing stolen goods, arson and operating gambling and vice operations.

“It is not astonishing that with a million Hebrews, mostly Russian, in the city (one quarter of its population), perhaps half of the criminals should be of that race when we consider the ignorance of the language, more particularly among men not physically fit for hard labor,” Bingham wrote with the stilted prose of a bureaucrat and the dubious authority of the then popular pseudoscience of eugenics.

Bingham buttressed his accusation with statistics: “Forty per cent of the boys at the House of Refuge and twenty per cent of those arraigned in the Children’s Court” are Jews, he claimed. “The percentage of Hebrew children in the truant schools is also higher than that of any other.”

Jewish leaders saw Bingham’s accusations as all the more dangerous because they were based on a shred of truth: “They knew, for one thing, that there was a crime problem on the East Side, not so lurid as Bingham had painted, but serious enough,” wrote Irving Howe in his history of the period, “World of Our Fathers.”

Like Somali-Americans in Minnesota, the Jews of the era were on the cusp — with one foot in the poverty of the tenements and the other in the growing prosperity of a rising working and business-owning class. But the Eastern European Jewish newcomers also had an important lever: the German Jews who had arrived earlier and established positions of power in finance and politics.

Jacob Schiff, the powerful banker and philanthropist, became one of the most forceful critics of Bingham’s article, publicly denouncing it as reckless and un-American. Joseph Seligman, founder of the investment bank J. & W. Seligman & Co., similarly condemned Bingham, insisting that crime was a function of poverty and dislocation, not religion or ethnicity, and pointing out the danger of a police commissioner racializing crime. Both men brought their own statistics and experts to show Bingham had exaggerated Jewish involvement.

The grassroots response was just as strong, with letters to the Yiddish and general newspapers, mass protests and heated sermons.

“Mr. Bingham has been indulging in mere generalities and he should be forced to give facts, including the names, residences, in fact the exact figures of any one week or month, to prove his statements, or else he will be asked to make a public retraction and apologize to the race he has injured,” fumed Rabbi Joseph A. Silverman of New York City’s Temple Emanu-El.

Bingham was, and he did. “By mid-September,” Howe writes, “under severe pressure, Bingham retracted his charges ‘frankly and without reservation.’” He subsequently lost the support of Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. and was forced to resign in July 1909.

Bingham wasn’t the only figure to hold the entire Jewish community responsible for the crimes committed by its members. Eleven years earlier, police commissioner Frank Moss argued in his book “The American Metropolis” that “criminal instincts… are so often found naturally in the Russian and Polish Jews.” Between 1907 and 1909, McClure’s Magazine published articles by the muckraking journalist George Kibbe Turner claiming extensive Jewish involvement in the “white slave trade” — what today we would call human trafficking. While courts found little evidence of a wide-spead Jewish conspiracy to traffic women, “McClure’s used the white slavery investigation and grand jury to stoke anti-immigration and anti-Semitic fears throughout the city,” historian Mia Brett wrote in a paper for the Gotham Center at CUNY.

The Jewish elite counted Bingham’s retraction as a victory, but the incident left many with the impression that the Jewish community needed a better mechanism for organizing around the fight against antisemitism. In New York, that meant the formation of the Kehillah, an ambitious experiment to create a unified Jewish communal organization. The Kehillah included educational and political committees, as well as a “Bureau of Social Morals” — a sort of self-policing body meant to help law enforcement root out crime among Jews. When it sank in that the bureau was only reinforcing an impression that the Kehillah had been formed to dispel, the bureau was scrapped.

The Kehillah lasted until 1922, when it disbanded over — spoiler alert — ideological disagreements among its constituent groups. But it created a precedent for centralized communal organizations to come, including UJA-Federation of New York.

In Minnesota too there are signs that the president’s attacks are strengthening the Somali community by sparking solidarity and organizing.“I think it’s giving us a chance for many Americans to learn about the Somali community, and not only that, but also to see the resilience,” Jaylani Hussein, executive director of the Minnesota chapter of CAIR, told CNN. “Also, it’s giving Somali Americans a chance to own their American identity and fight for it.”

When the Bingham incident is remembered, it is often to illustrate how officials trade on xenophobic fears over facts — and why such scapegoating, once unleashed, can do profound damage to both the targeted community and the civic fabric.

“We know that when a few people commit crimes, it does not implicate an entire community and to say so is racist, is xenophobic and just wrong,” Rabbi Adam Stock Spilker of Mount Zion Temple in St Paul told Fox 9 in Minneapolis last month.Meanwhile, the current police chief in Minneapolis, Brian O’Hara, has taken the very un-Bingham-like position that the “real problem” of social service fraud in the state doesn’t justify the “largely political” reaction of the federal government, especially immigration authorities.

“I had not known any Somali Americans until I moved to Minnesota,” O’Hara said Monday on “The Daily” podcast. “The Somali Americans that I have met here, including many of whom are police officers in this city, have been incredibly welcoming of me. From a personal perspective, [the immigration crackdown on Somalis] was just bizarre because I’m also aware that the overwhelming majority of people from that community are American citizens.”