Was Jesus A Vegetarian — Along With An Ancient Jewish Sect?

Image by Courtesy of Renee Senogles

When it comes to the history of vegetarianism, Jews have been swearing off meat for a very long time. “See, I give you every seed-bearing plant that is upon all the earth, and every tree that has seed-bearing fruit; they shall be yours for food,” it is written in Genesis 1:29. Many scholars take this to mean that the ideal Jewish diet is meant to be vegetarian.

In fact, the biblical commentator Rashi wrote that God “ did not permit Adam to kill any creature and to eat its flesh, but all alike were to eat herbs.” The diet in Eden was vegetarian, biblical scholars agree, and according to food writer Paola Gavin, the modern Jewish diet can be as well.

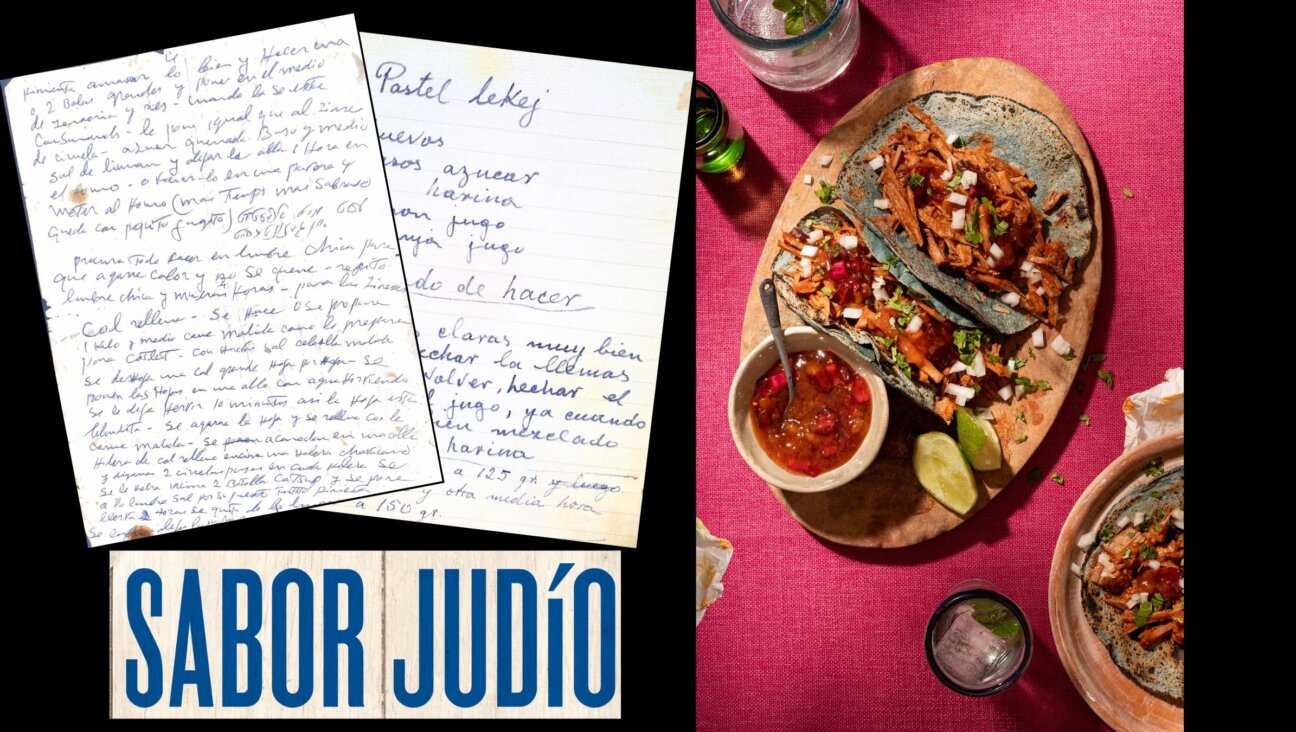

Gavin took a quest through the annals of Jewish vegetarian history, a quest that traversed twenty countries and resulted in 140 recipes, all compiled together in the form of her new cookbook, Hazana: Jewish Vegetarian Cooking.

‘Hazana’ means nourishment in Hebrew. The book itself is replete with explanations, from quick descriptions of the major Jewish holidays (and vegetarian options for what to serve at each) to an anthropological investigation of Jewish history and culture from country to country. From places like Hungary, where retes, or strudels, were made, to the Romanian pandispan, or sponge cake, that Romanian Jews ate, Jewish culinary traditions are seen as adaptive and varied, diverse and global.

“The table was well spread with all manner of fruit, beans, greenstuffs and good pies, plum water tasting like wine, but of flesh and of fish there was never a sign. …” wrote acclaimed author S.Y. Agnon about his fantasy of a vegetarian Shabbat. Hazana is a comprehensive, international glimpse into the future S.Y. Agnon dreamed of, the dream of a Jewish vegetarian utopia.

I interviewed Paola Gavin about the history of Jewish food culture, ancient Jewish vegetarian sects and whether Jewish food can survive without chicken soup.

Image by Courtesy of Renee Senogles

Shira Feder: I absolutely love the history of Jewish food culture that you wrote about in the beginning of the book. I was wondering if there was anything you learned over the course of your research about Jewish heritage that shocked you.

Paola Gavin: Well, yes, there was. Firstly, I had no idea that hundreds of Jews were burnt at the stake during the Spanish Inquisition. Nor did I know that Jews were often forced to eat pork in public (a horrendous thought for a vegetarian). This is why they were often referred to as ‘Marranos’ which means ‘pork’ or ‘swine’ in Spanish.

I was also shocked by the treatment of the Jews during the Shiite Safavid era in sixteenth-century Persia. At that time, Jews were treated as najis, or ‘unclean’, so they were not allowed to use public baths or drink from a public well. Nor were they allowed to walk on the same street as Muslims when it rained or snowed, lest they inadvertently ‘splashed’ them.

I love hearing about people’s food stories. Can you tell me one of yours? Like a dish you never thought you’d cook or a food you ate in an unexpected place?

I will always remember going to a famous restaurant in Positano, Italy, called Vicenzo’s. It was so good we went there every night for one week. Vincenzo loved to cook and every night he would prepare something special, then give everyone in the restaurant a sample to taste. I remember my ex-husband and I told him we were very fond of aubergine parmigiana – the well-known Neapolitan pie made with layers of fried aubergine, tomato sauce, mozzarella and grated parmesan. So every night Vincenzo made us a different variation. The first night he coated the aubergines in a light batter before frying them, the following night the aubergines were lightly dipped in flour. The night after that, he added a little beaten egg. Another time he added a few olives and capers. Then he made it without the tomato sauce. The next night he included slices of hard-boiled egg and on our last night he used the same ingredients to make stuffed aubergines. All I can say is that every way was delicious.

Jewish food culture is so diverse and has spanned the boundaries of every single country in the world. Are there any foods that are indigenous to Jewish culture?

I suppose the food that are truly indigenous to Jewish culture would be the foods that are mentioned in the Bible such as wheat, barley, figs, grapes, olives, pomegranates, and honey. Of course, like in most Mediterranean countries, the diet of the ancient Israelites was based on the trinity of wheat, olives and wine. Meat was rarely eaten except on festivals and special occasions. Bread was the staff of life, supplemented with lentils, broad beans, peas and wild herbs. Foods were usually sweetened with honey or a syrup made from dates, figs, or carob beans. They also enjoyed fresh curds made from sheep’s or goat’s milk. Riffot or bulgur – a cereal made from partially cooked cracked wheat – is also mentioned in the Bible. In fact one of the most famous Jewish dishes is Esau’s ‘porridge – a lentil stew made with brown lentils and bulgur, garnished with fried onions – that is still prepared all over the Middle East today. It is also used to make tabbouleh – the well-known bulgur salad with chopped parsley, tomatoes, spring onions and fresh mint.

You wrote about one ancient Jewish sect – the Essenes, who were staunch vegetarians, and about how the Jewish concept of vegetarianism dates back to the Garden of Eden. That was utterly fascinating! Can you tell me more about that?

The first reference to Jewish vegetarianism is in the Bible, when God said to Adam and Eve: “I have given you every herb-bearing seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat. And to every beast of the earth, and every fowl of the air, and to everything that creepeth on the ground, wherein there is life, I have given every green herb for meat: and it was so.” (Genesis 1”29-30).

Also, as I write in the introduction to Hazana, in Judaism, as in Hinduism, the eating of meat is thought to increase the animal nature in man. The Jewish dietary Laws forbid the eating of meat ‘in which its life blood still runs’ as this is thought to contain the spirit, emotions, and instinct of the animal.

You ask me about the Essenes. I have always been interested in the Essenes. They were an ancient, Jewish sect living in Judaea between the second century BC and the first century AD, who were strict vegetarians. The Essenes recommended eating a simple diet of fresh fruit, vegetables, barley, wheat, almonds, milk and honey – which they claimed would keep you healthy and lengthen your life. According to the first century historian, Josephus, the Essenes lived a similar kind of life to the Pythagoreans in Greece – and Pythagoras lived to be 103. Some people think that Jesus was an Essene.

A lot of people have a vision of Jewish cuisine as dependent on meat, like what’s Shabbat dinner without roast chicken or chulent. Your cookbook really presents an alternative vision of the Jewish cook as vegetarian, with a tremendous variety of dishes to cook. What made you focus on Jewish vegetarianism in this cookbook? Was it for ethical reasons, or health reasons?

The main reason is that I am a vegetarian myself and have been for decades. I didn’t become a vegetarian for ethical reasons. I was very interested in health when I was in my early twenties (and still am) so I thought I would try to be vegetarian – as an experiment. In fact it felt so good that I just continued. I also lost a little weight – very slowly without dieting – and it stayed off. Looking back, I think it was the best decision I ever made. I am convinced that it is a much more healthy way of eating.

Shira Feder is a writer for the Forward. You can reach her at [email protected]