Why the humble onion is the most Jewish allium of all

This versatile root vegetable has a cross-continental history in Jewish cuisine

Who needs manna from heaven when you have onions? Photo by Liza Schoenfein

Considering its prosaic nature, the ordinary onion certainly garners its share of poetic prose. Take this line from Mark Kurlansky’s new book-length ode to the allium, The Core of an Onion: “The onion is an extraordinary lily, certainly more talented than other lilies.”

Honeyed language indeed for a vegetable that will make you cry.

He continues: “Lilies generally do not know how to defend themselves. But if the bulb on an onion is attacked, it spits back with a ferocity unmatched by other plants.”

Perhaps Jews, as a people, find this quality relatable. Their affinity for onions certainly goes way back — as does their penchant for a good kvetch. After God parted the Red Sea for them, the formerly enslaved Israelites, who had eaten onions in Egypt, couldn’t help but register a gripe about the new bill of fare, which, as we know, consisted entirely of manna from Heaven.

“This was apparently an unenviable situation,” Kurlansky writes. The Hebrews complained to Moses that they missed garlic, leeks, and onions, among other foodstuffs.

“They missed the whole onion family,” Kurlansky writes. “Moses was not pleased. If you free your people and give them food from God, you don’t expect them to complain, ‘But where’s the onions?’”

To which I counter: Get to know us.

In any case, onions henceforth made it into all manner of Jewish victuals, including a notable variety of breads such as onion bagels, onion-and-poppy-flecked bialys and their predecessor, pletzel.

“In Bialystok these were called Bialystoken Tzibele Pletzel Kuchen, or ‘Bialystock Onion Pletzel Cakes,’” Joan Nathan writes in King Solomon’s Table. “Also called ‘onion boards’ when large, these pletzel became bialys on the Lower East Side of New York.”

Beyond the breads, there are Syrian stuffed onions called mechshi, Cochini-Jewish stuffed onions called mahashais, onion kugels, eggs and onions, chopped liver enriched with caramelized onions, and soups and stews of every stripe embellished with that extraordinary lily.

“I don’t think there’s one Shabbat stew that doesn’t have onions,” cookbook author Adeena Sussman said in a recent interview. “They’re essential in those long-cooked dishes because they bulk out the dish and add sweetness and caramelization. Think of the transformation of an onion from its raw form to its cooked form. It’s quite an evolution.”

The common round onion, allium cepa, is a perennial that farmers do not treat as such, because its bulb — which would otherwise remain in the ground to live another year — is picked before the plant has a chance to flower. To toughen the skin and make the vegetable long-lasting, it’s subsequently cured in a warm, dry place. And then we eat it — though the cook is likely to suffer.

“The toxic spittle the vengeful onion sends into your eyes is low-molecular-weight substances with sulfur atoms,” Kurlansky explains. There are a number of different compounds, including one that causes onion breath and another that makes you cry: “The molecules dissolve into the water of the eyes and turn into sulfuric acid, a nasty little trick designed for defense.”

All these compounds are unstable, which explains the alchemy that transforms the sharp flavor of the raw vegetable into something that, as Sussman noted, sweetens as it sautés. (Onions contain dextrose, which is coaxed out with slow cooking.)

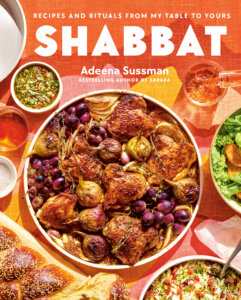

Sussman, whose most recent cookbook is called Shabbat, recalls in the book that growing up, her mother’s go-to Sabbath chicken was baked on top of a big bed of onions. “It was our Friday-night staple, the one my mother made almost weekly, but we never tired of,” Sussman says. She explains that her father and sister have somewhat different recollections of the dish. Perhaps there were carrots, or maybe celery …

“But I remember just onions,” Sussman writes, “and lots of them, which became schmaltzy as the chicken pieces roasted and released their juices right into the roasting pan.”

As in most Jewish cookbooks, onions show up everywhere in Shabbat.

“They’re so versatile, and because they’re shelf stable and inexpensive they’ve always been a staple in Jewish culture,” Sussman told me. “I think of them as being cross-cultural in Jewish cuisine. They can add a lot of sweetness, texture, and body to a dish. And at least in Ashkenazi cooking, where there was a limited spice palate, they were essential to the flavor of many dishes in raw and cooked forms.”

Her Ultimate Egg Salad recipe calls for three onions thinly sliced, which are caramelized slowly and piled atop the chopped, mayonnaise-swathed eggs.

“Use the serving spoon to drag as many onions into your personal serving as you like (and I predict you’ll like a lot),” she advises.

Her kaved katzutz (chopped liver) is also enriched with loads of caramelized onions, and onions stand alone in the “allium extravaganza” that is her Balsamic-Glazed Onions and Leeks, a combination that also includes shallots and garlic, all baked together until burnished and meltingly tender. Try it yourself if you want a good cry. (Or if you don’t, try soaking the onions in ice water for half an hour or so before slicing, which should impede their fierce mechanism of defense.)

Balsamic-Glazed Onions and Leeks

Ingredients

- 3 medium leeks

- 3-4 medium red onions

- 6 small-medium yellow onions

- 6-8 shallots

- 10-15 large garlic cloves

- 3-4 fresh sage, oregano, and/or thyme sprigs

- 1 1/2 cups vegetable broth

- 1/4 cup balsamic vinegar

- 1/4 olive oil, plus more for drizzling

- 2 tablespoons pomegranate molasses, honey, or maple syrup

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

Directions

- Preheat the oven to 425 °F.

- Bring a large pot of lightly salted water to a boil. Fill a large bowl halfway with ice, then add water to create an ice bath. Trim the root ends off the leeks as well as any tough dark green ends, then score them lengthwise halfway through with a paring knife; do not cut all the way through. Fan the leeks, rinse well with water, and cut into 3- or 4-inch lengths. Peel the papery outer layers from the red and yellow onions, then trim 1/2 inch off both ends.

- Place shallots in boiling water, boil for 2 minutes; use a spider or slotted spoon to remove them to the ice bath. Lower red and yellow onions into the water; boil 5 minutes, then lift out into the ice bath; chill for 3 minutes. Pop shallots out of their skins, and remove outer papery skins from the onions. Use a paring knife to cut a one-inch “x” into the bottoms of the red and yellow onions. Stand the onions up in a 10- or 12-inch skillet or round baking dish, then wedge the leeks in and around the onions. Fit the shallots in (everything should be quite snug in the skillet, but if there’s a little space, that’s OK), scatter the garlic, and arrange the herb sprigs on top.

- Whisk together the broth, vinegar, olive oil, pomegranate molasses, salt, and pepper in a bowl, pour it over the vegetables, and drizzle more oil over the top. Seal tightly with foil and bake until the onions are tender and can very easily be pierced with a fork, 1 hour 30 minutes.

- Uncover, reduce the heat to 400 °F, and cook until everything is golden brown and the liquid in the pan thickens slightly, 35 to 40 minutes. Season with salt to taste, then serve the onions and leeks with their liquid.