The shul knocker: The protagonist of Rosh Hashanah Eve

Although shul knocking may seem like a low-status profession today, shul knockers were held in high regard in the shtetl.

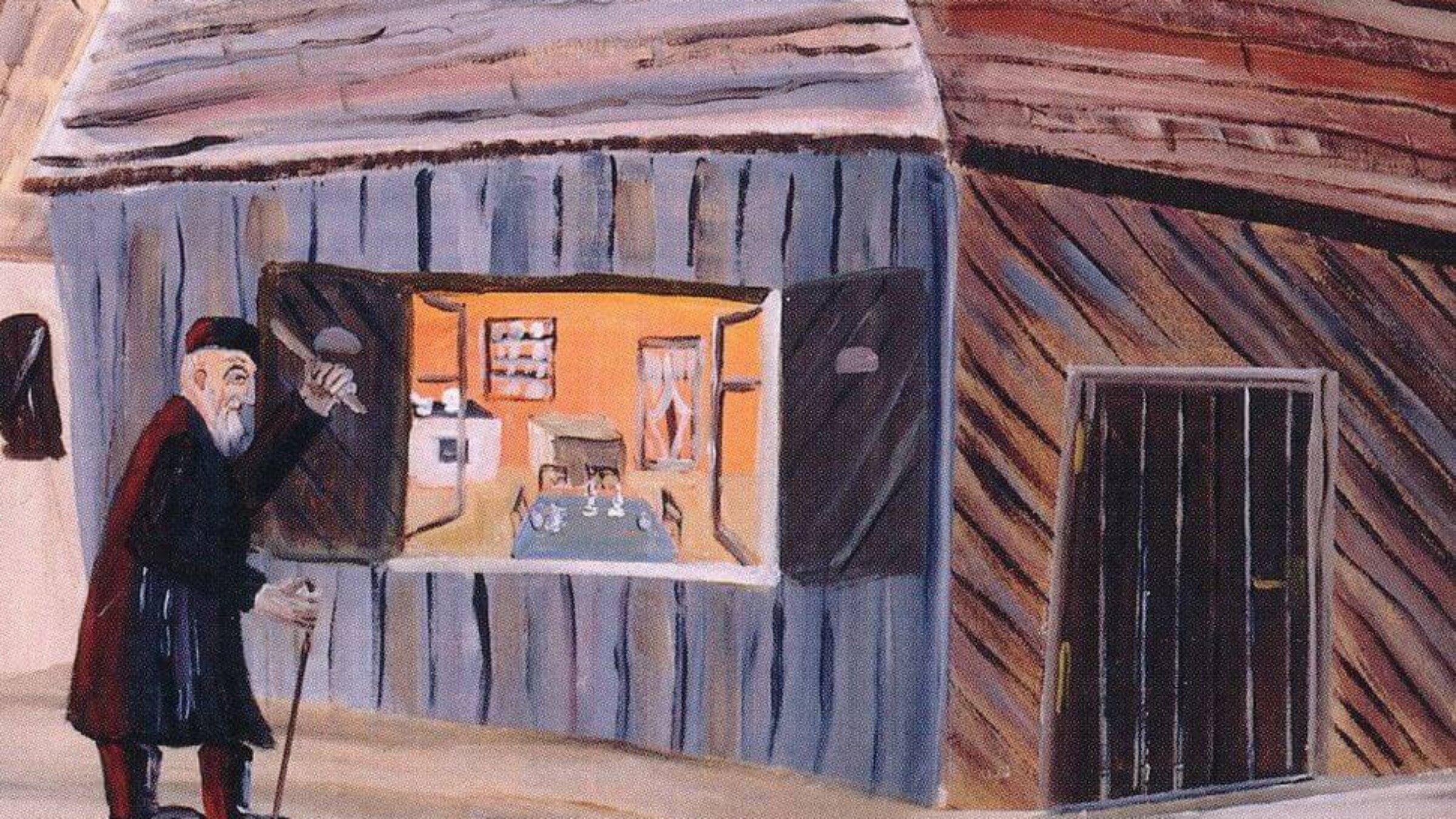

“Shulklaper”, c. 1995, from the book, “They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland Before the Holocaust” Image by MAYER KIRSHENBLATT

This article originally appeared in the Yiddish Forverts.

In the shtetls of Eastern Europe, the shul knocker (Yiddish: shulklaper or shulrufer), often the synagogue’s beadle, would wake up his fellow congregants in time for morning prayers and in the middle of the night for slikhes or slichos, the penitent prayers recited throughout the month leading up to the Days of Awe. He would rap on the shutters with a little hammer each day except on Shabbos when he used his fist.

The oldest mention of a “shul knocker” is from 1225 in Germany. But letting the residents of a town know when it was time to pray is apparently a much older tradition: in the second century CE, the prayer leader summoned his congregants by blowing a shofar.

Although shul knocking may seem like a low-status profession today, shul knockers were held in high regard by medieval Jews. Because the shul knocker went from house to house he was known by everyone in town, even by his Christian neighbors. Some communities kept his little hammer inside the Torah ark. Often the number of raps made with the hammer was kept the same from generation to generation. In Sephardic communities, beadles also went from house to house to awaken Jews for prayer, though without a hammer.

A beautiful description of a shul knocker appears in the memorial book written about the Polish shtetl Sochaczew (Yiddish: Sokhatsher). Moyshe Aron Shulklaper would rap three times on the closed shutter with his wooden hammer. If anyone had died, he would rap only twice. “The third rap of the hammer which never came hung in the air, provoking a shudder in all who heard it. It signified death, the cemetery, bathing a corpse and a funeral. A sigh would escape from your chest and tears would well up in your eyes.”

And so Moyshe Aron Shulklaper became the “announcer of joy and sorrow.” His third rap of the hammer was always awaited with hope. It seems that these feelings about the shul knocker go way back. One source, A. Ziskind, wrote in the 16th century: “When the shul knocker rapped only twice, I’d sigh. But when he tapped three times, my heart jumped for joy.”

When Moyshe Aron Shulklaper went to the noisy market on Friday afternoon and began rapping with his hammer on the shutters of the open stores to announce that Shabbos was coming, chaos often ensued. Both storekeepers and their customers rushed to finish their transactions.

The words the shul knocker cried out before slikhes became a song. The song’s first line was usually: “Arise Jews (or children), to serve the creator! Arise for slikhes!” The Galician Yiddish writer Gershom Bader noted that in Krakow, the shul knocker would go from house to house during slikhes singing “Jews, kosher Jews, dear Jews, arise, arise for slikhes.” Instead of knocking on every window, though, he’d only rap upon the windows of those who had given him a donation.

In the days before Rosh Hashanah, the shul knocker summoned the Jews differently, “calling upon the ancestors.” He sang:

“Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, David and Solomon,

Arise! The Jews are in exile,

Arise to your holy slikhes.”

The shul knocker would then rap on the synagogue gates and call out to rabbis of yore in heaven: “Arise and entreat on behalf of the Jews!”

The figure of the shul knocker is so picturesque that he often appeared in literary depictions of the shtetl. In his autobiographical novel “Shloyme Reb Chaim’s” Mendele Mocher Sforim writes about Yudl the shul knocker, who was a cobbler by trade. Unlike in other communities he rapped twice on the window to summon the Jews to prayer and three times when someone had died. He also rapped on the window on Friday afternoons, yelling “Jews to the bathhouse!”

During slikhes, he not only knocked but also opened the shutters until he was sure that the people inside had been woken up. The community didn’t pay him for his labor but he was invited to every wedding and celebration in town. Mendele Mocher Sforim writes that the fact that the same person summoned the Jews to both synagogue and the bathhouse markedly raised the prestige of the later.

And what does the tradition of rapping on shutters to wake up Jews in time for synagogue look like today? Instead of the traditional shul knocker, members of the Belz Hasidic community in Meah Shearim are awoken by a car with a loudspeaker blaring the old song “Arise for Slikhes.”

You can hear a popular version of the song performed by Yermiah Damen here:

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO