Feeling at home in my Yiddish-speaking bubble

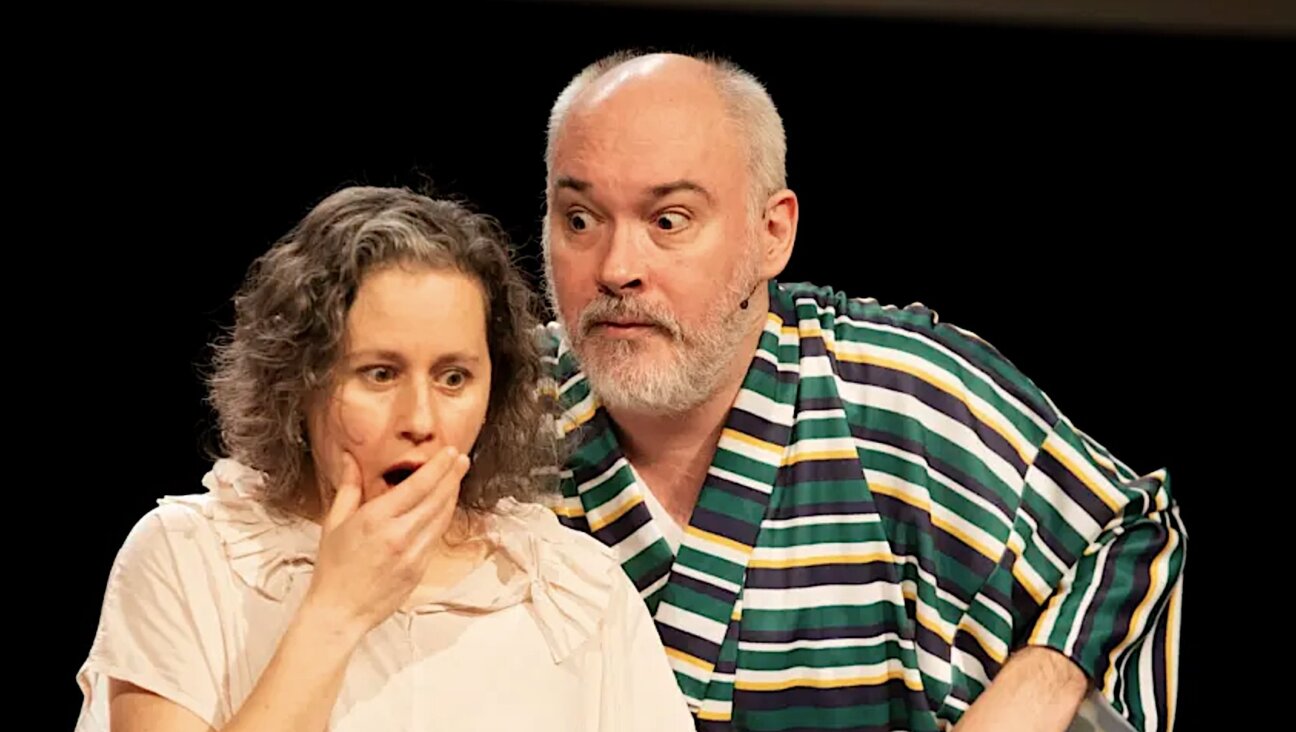

The ten students in my Yiddish class are of differing political persuasions but we’re united in our love of the language.

Courtesy of Yiddish Book Center

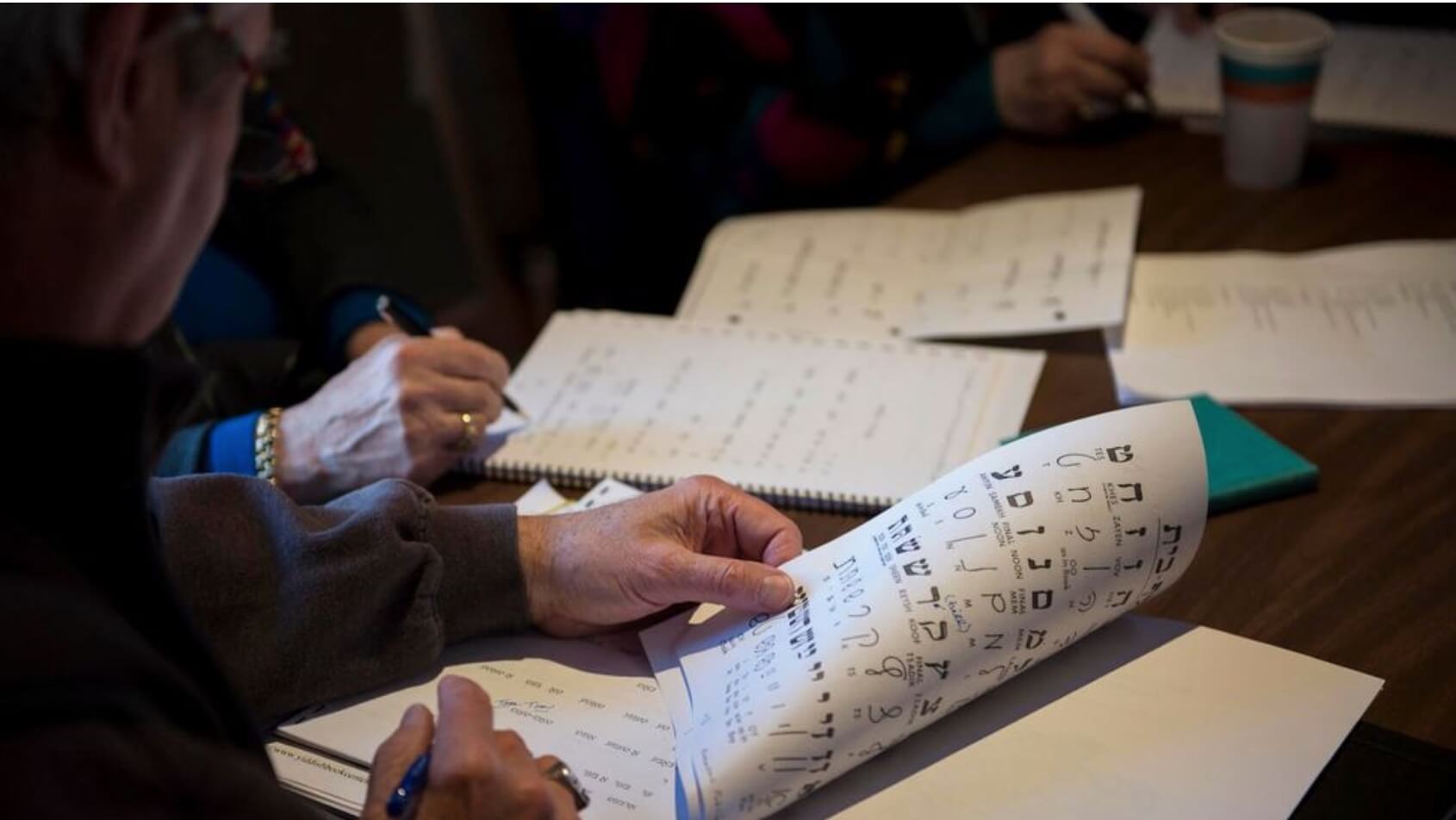

Up until COVID, I started my Tuesday evenings shlepping on the subway to the mid-Manhattan Workers Circle for a Yiddish class. As a child, I’d studied the language in an afternoon shule/school in the Bronx. Now, decades later, I felt a quiet pull to study it once again.

Kolya Borodulin is the director of Yiddish programming at the Workers Circle as well as our Tuesday night teacher. He is warm and impassioned, pacing up and down our classroom, literally bending over backwards or dropping to one knee, and doing all manner of spontaneous gymnastics to make a point.

Unlike my former Yiddish teachers, Kolya was raised as a Soviet citizen and not in a Yiddish-speaking world. Yet his accent is the same one I remember from 50 years ago. I could listen to his flawless, Old World pronunciation for hours.

“Nu, haynt hobn mir a sakh tsu ton/today we have a lot to get through,” says Kolya and he means it. In our packed hour and a half lesson, someone will give a synopsis of a news piece from the Yiddish press, we’ll take turns reading the story or novel we were assigned, we might sing a song, watch a PowerPoint presentation about an author or answer questions about our holiday celebrations. “I am stingy,” he says to us in Yiddish, “stingy with our time, of which there is never enough.”

There are ten students in the class, and though we are of differing ages and political persuasions, we are united in our love of the language.

Mordkhe (aka: Marty) taught psychodrama in the 1960s before switching to making a living at a tech firm. He is my seat mate and vocabulary savior. Some weeks I am too rushed to look up unfamiliar words in our reading, but Mordkhe is tireless and his homework sheets are marked up with yellow highlighter and above those highlighted words, the English translations. I always grab a fast look at his pages before class starts.

Across from us, two sisters, Yehudis and Batsheva (aka: Arlene and Sylvia) are giggling about something on their phones. Effervescent and chatty, they never hesitate to ask if they don’t understand something or to complain about the way women are treated in the stories we read. Kolya sighs each time they bring this up and explains that it was a different era then. And in a way, that’s precisely why we are there each Tuesday evening. We are immersing ourselves in that lost East European world, sometimes for worse sometimes for better, from which most of us descend.

Because Kolya has so much material, he starts every class punkt (exactly) at 6:30. This can be challenging for some professionals, and today, two people wander in closer to 6:45: Shaye, a psychotherapist, whose makeshift dinner of coffee and danish sends a sweet smell into the classroom air and Mark, a young South African doctor. Mark is one of a handful of us who studied Yiddish formally in their youth. The rest of the class either heard it at home or took it up in adulthood. Most of us stumble our way through efforts at grammatically correct conversation with our English thoughts quicker than our verb conjugations.

But we can all read fluently, and today we are studying Israel Joshua Singer’s memoir, “From a World That is No More.” Singer’s mother, Batsheva, was extremely learned, but she could do little with that knowledge as a woman. She did raise three excellent writers though; Israel Joshua, his older sister, Esther Kreitman, and their Nobel Prize winning younger brother, who took his mother’s name in sympathy and became Isaac Bashevis Singer.

In Israel Joshua’s memoir, there is a scene in which his father, the local rabbi of Bilgorai, ponders recent tragedies in the Jewish world and concludes, based on this and kabbalistic numerology, that this is the year the Messiah will come. He and his congregants spend months in joyous anticipation of being carried on eagles’ wings to Jerusalem. When Rosh Hashanah arrives, they are certain there will be a sign to them while they are praying. But there is no sign. Nor during the Yom Kippur services. The next year’s numerical value doesn’t match up anymore, and Singer’s father is crestfallen that the harsh world they live in won’t give way anytime soon to Paradise.

My secular parents would have stared at me in alarm if I so much as hinted that I was waiting for the Messiah to come. Nonetheless, there is something about that raw faith that pulls me in to this and other writings about shtetl life. Of course, if I had been born there I would have been married off at an early age and spent my days cleaning and cooking, with no time to read and analyze stories. But from my current vantage point, I am free to covet what seems to be missing from my modern life: an iron sense of community, a blueprint for how you go about your days, and an abiding faith in Der Eybesther (the Eternal One). Although most of the writers we read left shtetl life – and sometimes their religious observance – their words conveyed a clear picture of material poverty alongside spiritual depth, frightening circumstances together with communal balm. At the very least, you knew who you were and how you fit into the larger framework. Kolya is dancing around the room, eager to make a point.

“Studentn,” he says, “Ot iz a bild fun der mishpokhe Singer/ Here is a picture of the Singer family,” and on the whiteboard in front of the class appear three black and white photographs with three unsmiling faces. Each sibling wrote colorful, vivid prose about the childhood they shared, but their later relations were strained. Kolya tells us that when Esther and her family were destitute in war-torn London, she wrote to her two brothers, both then publishing in New York, and asked if they could send some money. Neither one wrote back.

With five minutes left till the end of class, Kolya puts on a recording of Chava Alberstein. She is a popular Israeli singer who defied her country’s bias against the mamaloshn/mother tongue and put out several albums in Yiddish. Her deep, smoky voice fills the classroom with a popular song written in 1909, that tells the story of Chavale who goes out to the field to pick daisies. A young man confronts her there, woos her, calls her ‘the prettiest daisy of all,’ but leaves her alone and bereft once the sun has gone down. Yehudis and Batsheva roll their eyes.

There’s an old joke about WASPs not saying goodbye when they leave, and Jews saying goodbye but not leaving. So it’s not surprising that we take our time getting our coats once Kolya has implored us, as usual, to remain gezunt un shtark/healthy and strong till the next time he sees us. No one is in a rush to leave our Yiddish speaking bubble.

Mordkhe, my vocabulary savior, waits for me to pack up my notebook and pens and tie a woolen scarf around my neck. His subway stop is in the same direction as mine.

“Remind me again,” I say as we head out onto the street “how many years you have been coming to Kolya’s class.”

“Eleven years,” he replies. “Ever since that dream with my Zaide.”

And he repeats the story of how close he was to his Yiddish-speaking grandfather as a child. Whenever he would do something mischievous — pick up a screwdriver, get close to an outlet — the old man wouldn’t say anything but instead give him a withering “If I ever catch you again…” look. Decades later, when Mordkhe was diagnosed with throat cancer and the odds were not in his favor, his Zaide came to him in a dream. Reaching in, he pulled something from his grandson’s throat and gave him that same withering look. When Mordkhe awoke with a start, he said to himself, “If I recover, I have to do something for my Zaide.” His response to recovering was to enroll in a Yiddish class, leading him into a lifelong passion for Yiddishkeit.

Now that our class has been meeting virtually for over a year, I can’t peek at Mordkhe’s notes or watch the sisters giggle together. We still read our texts aloud but Kolya, sitting at his screen, can’t pace or gesticulate to make a point. Nonetheless, I am so grateful to be among cohorts — online or in person — who never make the mistake of regarding Yiddish as a punchline, but as a deep source of affection, counsel and reverence.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO