It’s not your grandparents’ Poland anymore. Or is it?

The late filmmaker Menachem Daum described two Polands in this essay — one of inclusivity, another of ethnic nationalism

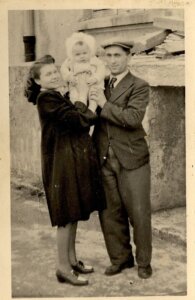

Photo by Menachem Daum

My father, Moshe Yosef Daum, returned to his Polish hometown of Zduńska Wola a week after the Germans retreated, to see if anyone from his family was still alive.

He was the only one. Of the over 8,000 Jews who lived in Zduńska Wola when the war began, he was among the 100 or so who survived. Upon seeing him some of his former Polish neighbors expressed their surprise and obvious disappointment. “So many Zhidkies are still alive?” they asked. Like many Jewish Holocaust survivors from Poland, he never returned, nor did he want any of his children to ever set foot on Polish soil.

Despite my father’s objections, I decided to visit Poland in December of 1988 in order to accompany and film Hasidic singer and storyteller Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, during his ten-day concert tour of major Polish cities. I told my father I would soon visit Poland and be in his hometown of Zduńska Wola. Realizing his objections would not dissuade me, he asked me to at least do him a favor. His own father, who had died when my father was only ten months old, was buried in the local Jewish cemetery. His mother remarried and my father had a difficult relationship with his stern and unsympathetic stepfather, often finding solace in the cemetery where he prayed at his father’s grave.

Now, in his old age, my father had suffered a series of debilitating strokes and was asking me to pray at his father’s grave for his recovery. He told me how to find his father’s tombstone: upon entering the cemetery’s main gate, go to the right, count ten rows along the back wall and then count four rows forward. I assured him I would do so.

When I got to Zduńska Wola a few days later I found the Jewish cemetery in shambles and overgrown with dense vegetation. Many tombstones were missing and most of those that remained had been toppled. There were a number of open pits where graves had been dug up. I learned this was mostly the work of locals who believed Jews had buried their valuables in the cemetery to hide them from the Germans. The sad condition of the cemetery seemed to confirm my father’s belief about Poles. They could not even let dead Jews rest in peace.

Following my father’s instructions, I counted ten rows to the right and four rows forward. Unfortunately, all the tombstones in that section of the cemetery had been removed or smashed into small fragments. I found no sign of my paternal grandfather’s tombstone. Nonetheless, I figured the tombstone is merely a pointer; what is most sacred is the actual resting place of my grandfather. Whether I was off by a few feet to the right or left was not so important. I said tehilim, the Psalms, which are traditionally recited at an ancestor’s grave, and asked my grandfather to intercede in Heaven and do whatever he could on behalf of his ailing son.

Later, when I returned to New York, my father asked if I had found his father’s grave. “Of course,” I said. “Your father’s tombstone was exactly where you said it would be, ten rows on the right side and four rows forward.” I figured even if the tombstone no longer existed in reality, let it at least continue to exist in my father’s memory.

The Poland my father hoped and fought for

My father was born in 1915 at a time when Poland did not exist as an independent country. For well over a century, Poland had been partitioned and absorbed by the neighboring Prussian, Austrian and Russian empires. In November 1918, under the leadership of Marshal Józef Piłsudski, Poland proclaimed its independence. The newly reconstituted Poland that emerged was only two-thirds ethnically Polish Catholic. The largest minorities were Ukrainians, Jews and ethnic Germans. This gave rise and urgency to the question of who is a “true Pole.”

Two answers emerged to the question of what constitutes Polishness. The first approach, the pluralist one, defined it as a community of cultural and historical values that was inclusive. These pluralists, championed by Piłsudski and his leftist Polish Socialist Party, adopted a tolerant stance toward Poland’s Jews and other minorities. Any member of a minority, including Jews, who embraced Poland’s struggle for freedom, was deemed a true Pole.

Diametrically opposed to Piłsudski’s approach was the exclusivist vision of Polishness espoused by Roman Dmowski, a founder of the right-wing National Democratic Party. The “exclusivists” deemed anyone who was not Roman Catholic or not of ethnic Polish descent to be outside the Polish national community. Dmowski and his party advocated a form of Polish ethno-nationalism that was hostile towards all Polish minorities but was especially bitter towards Poland’s Jews. Not only were Jews to be excluded from Polish nationhood, but they were seen as an internal threat to all things Polish, as the “anti-Pole.” This view saw Poles and Polish values as jeopardized by these “ungrateful guests” who had overstayed their welcome and abused the hospitality of their host country.

Piłsudski, the founding father of the Second Polish Republic, directly or indirectly ruled Poland for most of my father’s formative years. I recall my father speaking warmly of Piłsudski as a friend of Poland’s Jews. No doubt, it was Piłsudski’s vision of a multi-ethnic and tolerant Poland that my father hoped would prevail over that of the ethno-nationalists. In 1936, a year after Piłsudski’s death, my father received a draft notice from the Polish army. Until then he had spent most of his adolescence in religious study and in prayer together with other young Hasidic followers of the Rebbe of Ger. The Hasidic culture of his insulated environment could not have been more different than the secular culture of the Polish army. My father was concerned how he could remain an observant Jew there. He would be forced to shave off his beard and side curls, replace his Hasidic garb with an army uniform, even violate the Sabbath.

The Rebbe of Ger, who was a man of few words, told my father two things. First he said: “Fun dinen in militer kon men zikh lernen tzu dinen dem eybershtn” (by serving in the army you can learn how to serve the Creator). Then he added: “Vu a yid gefint zikh kon er shtendik blaybn a yid (wherever a Jew finds himself he can always remain a true Jew). These words fortified my father. For the nearly two years that he served in the Polish army he ate only raw fruits and vegetables that he got from the army kitchen, and eggs that he cooked in his own kosher pot. One night a week he was able to leave his army base and get a home-cooked kosher meal at the nearby home of a relative.

At the end of my father’s tour of duty, the commanding officer reviewed his military record and remarked: “It says here you fulfilled all your obligations to the Polish army, yet you never ate a single Polish army meal.” The officer stood up and discharged my father with a salute. My father always spoke with pride of his Polish military service and of his ability to remain true to his religious values.

By the time my father returned to civilian life, Piłsudski’s vision of an inclusive Poland had been replaced with virulent ethno-nationalism. The clique of military men who succeeded Piłsudski was unwilling or unable to rein in nationalist extremism. This “regime of the colonels” sought to find favor with Poland’s neighbor, Nazi Germany, hoping this would save Poland from invasion. In the four years leading up to the outbreak of World War II the Polish government passed laws against Jewish businesses, promoted economic boycotts, expelled Jewish students from universities and outlawed Jewish ritual slaughter. In August 1939, a month before the outbreak of the war, my father was again mobilized by the Polish army. He was captured in the first week of fighting and spent the rest of the war in the Zdunska Wola ghetto, the Lodz ghetto and the Hasag forced labor camp in Czestochowa.

Inheriting contradictory attitudes towards Poland

During the war my parents had each lost their spouses, children and extended families. After the war they met and married in Łódź which had by then become Poland’s largest Jewish community. Although they came from a similar background – both came from very observant Jewish homes – they would probably never have considered each other suitable marriage partners, had it not been for the Holocaust.

My mother, Fayga Mindel, came from the more affluent and respected Nussbaum family. During the day she attended Polish public school where she learned to appreciate Polish literature, poetry and art, and every afternoon she attended a Bais Yaakov religious school for girls. My father, on the other hand, studied in yeshiva and had little exposure to worldly knowledge or secular culture. Mainly what my parents had in common was their shared memories of prewar Zduńska Wola and their urgent postwar desire to rebuild new families. The sarcastic expression “Hitler iz geven zeyer shadkhn: Hitler was their matchmaker” certainly applied to them.

In Łódź my parents met many other Jewish survivors who were afraid of going back to their towns and sought safety in numbers. After a short stay they fled Poland for the safety of the American Occupied Zone in Germany. There, in the Landsberg Displaced Persons Camp, I was born in October 1946. They called me Menachem, which in Hebrew means “one who consoles or comforts.”

We were among the last displaced persons to leave Germany. With the help of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) we settled in Schenectady, NY when I was five. HIAS volunteers found a good job for my father and a nice place for us to live. They registered me in Schenectady’s Riverside Public School under the name “Martin” which I was told would be easier for people to pronounce than Menachem. They helped us get a TV set so we could learn English. I was adapting well to this wonderful new land, but my father was miserable. Many years later I obtained our family’s dossier from HIAS and learned that less than three months after we arrived my father was complaining that he didn’t belong in Schenectady. The director of the Schenectady Jewish Community Center, who was responsible for our re-settlement, agreed with my father and wrote to HIAS:

Apparently, it was a mistake to settle Mr. Daum here. His economic life, while endurable, is not sufficient to overcome his religious and spiritual needs. He is dissatisfied with the limited Jewish educational facilities that the community can provide for his older boy; kosher food is a big problem for him in Schenectady and he is apparently a soloist in terms of his religious needs, having neither a minyan (a prayer quorum) nor a group of people who have the same religious and cultural values.

As soon as he could scrape together enough money, my father moved us from Schenectady to a poor neighborhood in Brooklyn that contained a small community of Hasidic survivors. He registered me in a Hasidic yeshiva and joined a small Hasidic prayer house. There, in the company of survivors with similar backgrounds as his own, I saw him become transformed. As they chatted, they seemed to have traveled back to prewar Jewish Poland. They reminisced about their childhood and adolescence, their families, friends, teachers, colorful characters and spiritual pilgrimages to the Rebbe. They recounted humorous anecdotes that made sense only to those with a shared upbringing. When they talked about the past it was almost as if the Holocaust had never happened.

I enjoyed seeing my father become so animated. I especially enjoyed seeing him smile and laugh, emotions he rarely displayed. Witnessing the power which prewar Jewish Poland had on my father, I developed a nostalgia for a place I had never been to and for a time which no longer existed. Being a “Polish Jew” became an important part of my identity.

My own complicated relationship with Poland

My attraction to the prewar Jewish Poland of my parents increased over the years. When I heard Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach would be giving a concert tour of Hasidic music throughout Poland I jumped at the opportunity to join him. I knew that the tiny and mostly assimilated Jewish community still living in communist Poland was in no way representative of the diverse prewar Jewish community my parents had known but I hoped I could learn something from this aging remnant of Polish Jewry. I naturally assumed these Polish Jews would comprise the majority of Rabbi Carlebach’s audiences since I couldn’t imagine any Polish Christians coming out to hear Jewish music and stories.

I soon discovered how wrong I was. The vast majority in the audience were indeed Polish Christians. I asked them why they came and got a variety of answers. Some came out of simple curiosity to see the “Singing Rabbi.” Some came as an act of defiance against the then ruling communist authorities who had expelled thousands of Polish Jews in 1968. To show their objection to the communist’s “anti-Zionist” campaign many in the audience chose to become “anti-anti-Semites.” Some, who knew that the Hasidic movement had been born on Polish soil, saw this music as a “homecoming” of their own national history and culture.

For ten days I witnessed thousands of Poles dancing and swaying to Hasidic music and entranced by Hasidic tales. I saw countless Poles coming over to Rabbi Carlebach, a bearded yarmulke-wearing Orthodox Jew, asking to shake his hand or bless their children. These were not scenes I would have expected based on the depictions of Polish Christians I had grown up with.

In the years that followed I made many trips to Poland where I continued to encounter Christian Poles who were interested in things Jewish. On every visit, I made a stop in Zduńska Wola and noticed the Jewish cemetery looked a little cleaner and better maintained. Clearly there were local people taking care of it. The first of these I met was Elżbieta Bartsch, the director of a school in Zduńska Wola. Later I met Kamila Klauzinska, a graduate student at Krakow’s Jagiellonian University. Kamila went on to write her M.A. thesis about the Zduńska Wola Jewish cemetery and her PhD dissertation on Jewish genealogy. Kamila briefly appeared in a PBS documentary film I produced in 2004 called “Hiding and Seeking”, which tells the story of my family’s journey to Poland to search for the Polish farmers who risked their lives for 28 months to hide my father-in-law and his two brothers. (“Hiding and Seeking” can be viewed free of charge at https://vimeo.com/497317050. Password: Menachem).

In 2007 Kamila invited me to a rededication ceremony for the restored Zduńska Wola cemetery. The following year she invited me back to Zduńska Wola for a gathering she had organized called the First National Conference of Poles who Preserve Jewish Memory. I was moved by the dozens of Memory Keepers who came from all across Poland to attend the event.

For many decades after WWII, the Memory Keepers were mavericks, lone voices speaking out about Polish-Jewish history being an integral part of Polish history. But in 2014 it seemed as if their iconoclastic views had finally become mainstream. That was the year I returned to Poland to attend the opening of the Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews. This impressive institution, built in Poland’s capital city and partially funded by the Polish government, documents nearly 1,000 years of Jewish life in Poland. At the opening ceremonies I watched as a Polish military honor guard solemnly placed wreaths at the memorial to the Jewish fighters and victims of the Warsaw Ghetto. I felt tears welling in my eyes. These Polish soldiers were wearing the same military cap and uniform my father had once worn. I could only wonder what his reaction would have been to this.

I wondered the same when Polish President Bronislaw Komorowski, flanked by Polish and Israeli flags, stood up afterwards and said: “It is impossible to understand and fully appreciate Polish history without knowing the history of Polish Jews, not only because of the many centuries Jews lived on our soil, but also for the contributions of Jews to many aspects of Polish life – to the economy, culture, and science.”

I couldn’t believe it. It seemed as if the liberal, tolerant and open Poland long ago envisioned by Marshall Piłsudski had finally and miraculously become a reality.

The Museum opening aroused an unknown reservoir of Polish pride I didn’t even know I possessed. I wanted to do something concrete to show my support for the direction Poland was now taking. I returned home with much enthusiasm and great hopes for Poland’s future. I ignored the cynical reaction of some of my friends who dismissed the museum as a public relations ploy to deflect attention from Poland’s anti-Semitic image or as a way to draw Jewish tourist dollars to the country.

I decided to embrace the “Polish” side of my Polish-Jewish identity. I always sensed there was something distinctively Polish about Polish Jews, something that makes us different from Russian or Hungarian or German Jews. I realized that my ancestors, who had lived on Polish soil for centuries, had to have been influenced by their Polish neighbors, their culture, their cuisine,, by the very air of Poland. As a symbolic gesture of solidarity with my “Polishness,” I obtained Polish citizenship.

However, only a year after the museum’s opening, I and many of my Memory Keeping friends were disheartened by the results of Poland’s presidential election. The lead-up to the election revolved around issues not specifically related to Polish-Jewish relations, but rather with fatigue with the party in power, anti-establishment feelings, economic worries and a growing rejection of the idea that Poland should open its border to Muslim refugees from the Middle East. And yet, the first question in the presidential debate did not involve any of those issues. Instead, it involved a pointed question from the challenger to President Komorowski about an apology he had made for the massacre of Jews in the town of Jedwabne by fellow Polish citizens. Why had he “failed to defend the good name of Poland?” they charged.

President Komorowski, who greatly impressed me with his open-mindedness at the museum’s opening, ended up losing the election. The new government took a pronounced rightward turn which energized and invigorated the country’s resurgent ethno-nationalist groups. The government is not overtly anti-Semitic but it tolerates mass demonstrations by nationalists who openly call for “Poland for Poles” and who proudly wear the insignia of Poland’s prewar anti-Semitic parties. It also avoids openly condemning the ethno-nationalists for fear it would lose their support.

In 2018, as a way of further placating this constituency, the government passed a controversial law that outlaws blaming the Polish “nation” for crimes committed during the Holocaust. It’s unclear whether survivors like my father would be in violation of this vaguely worded law if they recounted instances they witnessed of Poles who blackmailed Jews in hiding, handed them over to the Nazis or killed Jews themselves even when no Nazis were around. This law represents an unambiguous attempt to re-write history and is vigorously opposed by Poland’s Memory Keepers. Despite their remarkable progress, it was clear that the brave work of Poland’s Memory Keepers remains unfinished.

I would like to show the Memory Keepers that I stand with them. As an American I support their fight for a more tolerant, open, democratic and self-critical country. As a Polish citizen I support their fight for Poland to live up to its most noble Polish ideals, to bring to fruition the Poland my parents and millions of Polish Jews once hoped for. As a Jew I support them for doing the sacred work which Jews all over the world should be doing; caring for the millions of our ancestors laying in abandoned cemeteries on Polish soil.

Epilogue

As I was preparing to go to Poland in 2005, a few months before my father’s death, I went to say goodbye to him. At this point his physical condition had greatly deteriorated. He couldn’t walk and barely talked. He couldn’t even swallow. He had to be fed through a gastric feeding tube. I assumed he would ask me to pray at his father’s grave, as he usually did. Instead, in a barely audible voice, he said, “Nem mikh mit (take me with you).”

I couldn’t believe that my father, who had always refused to return to Poland, had changed his mind. Maybe he misunderstood me, I thought. So I asked him, “Where do you want me to take you?”

“Home.”

“Where is your home?” I asked.

His reply: “7 Stęszycka Street.”

–––––––––––

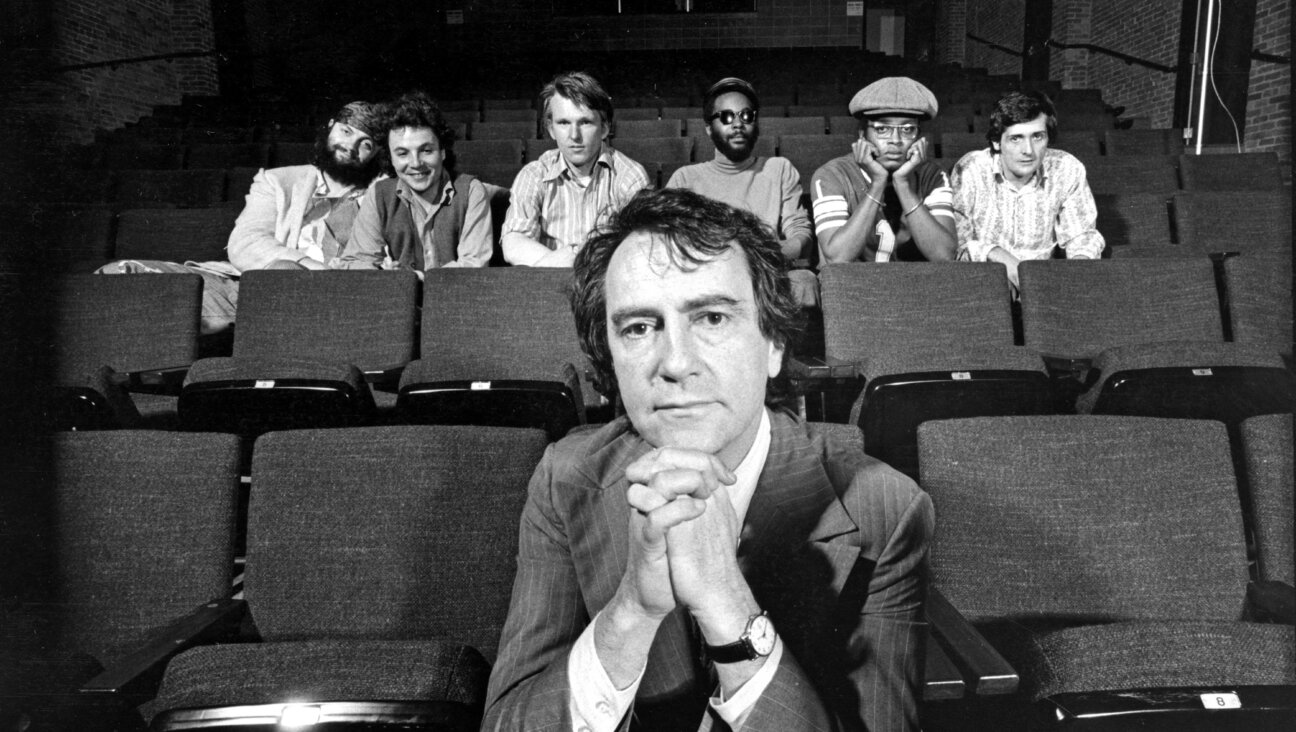

Menachem Daum produced and directed several acclaimed documentary films, including “Hiding and Seeking”, about his search for the Polish farmers who saved members of his family during the Holocaust. He is currently at work on “Gone But Not Forgotten” about Christian Poles who preserve the Jewish heritage sites that were sacred to his parents and ancestors.