How Tu B’Av, the ancient Jewish holiday of love, was revived

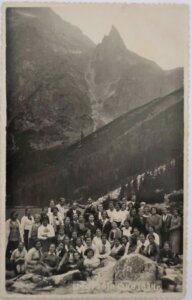

In 1932, a group of Orthodox girls celebrated the holiday by taking a nighttime hike into the woods.

Photo by MENAHEM KAHANA/AFP via Getty Images

Sometimes, for whatever reason, the best traditions get left behind.

That seems to have been the case with the minor holiday of the Fifteenth of Av, Tu B’av, the midsummer festival described in the Mishna (Ta’anit 4:8) in which “the daughters of Jerusalem go out dressed in white and dance in the vineyards,” hoping to find a mate. For over a thousand years, this ritual was forgotten by the Jews as they wandered and settled in countries around the globe.

But for us modern Jews, a Jewish holiday of love involving an outdoor rave is too tempting to ignore, so it’s no wonder that the holiday was revived in the 20th century. Today even the Orthodox community celebrates the one-day holiday of love, which begins this year on Thursday evening, Aug. 11. In one annual initiative, called “Tu B’Av Together: A Global Day of Shidduchim” (shidduchim means matchmaking), Jews around the world — led by rabbis — gather to pray for all Jewish singles to speedily find their match. For a small donation, any single man or woman can add his or her name to the list of unmarried people hoping to find their bashertn, their “destined one”.

The holiday was first observed, according to reports, in the kibbutzim of Mandate Palestine, where vineyards were a thing again: 1925 saw the first such celebration, among a group of kibbutzim in the Jezreel Valley. In today’s Israel, it’s known as “the Jewish Valentine’s Day.”

This is more or less how the story of the modern revival of Tu B’av is told today. There’s just one problem: The story’s missing an important piece. Although Tu B’av was revived among secular Zionists in Palestine in 1925, it was also brought back among Orthodox Jews in interwar Poland in 1926. But unlike today’s “Global Day of Shidduchim,” this revival did not involve a parade of men in beards, as is seen in so many other ultra-Orthodox events.

In fact, in a kind of inversion of the contemporary male-only Tu B’av celebrations on YouTube, it included no men at all. The Eastern European revival of Tu B’av began in February 1926, when the political organization of Orthodox Jewry, Agudath Israel, announced the founding of a youth movement for girls, Bnos Agudath Israel (commonly called Bnos). Shortly afterward, the Central Bnos Office in Lodz, Poland, circulated a pamphlet to its members describing Tu B’av as a newly revived “festival of Jewish daughters,” and providing instructions on how it might be observed.

By that summer, a periodical published by Bais Yaakov – the network of schools and youth movements for Orthodox girls – reported on Tu B’Av celebrations in 10 locations throughout Poland, including rented halls decorated with flowers and greenery, banquets, speeches by female speakers, singing and dancing.

In her published writings, Sarah Schenirer, who founded Bais Yaakov and was herself divorced at this time, de-emphasized the romantic elements of the holiday. She focused rather on its camaraderie and egalitarianism. This was a holiday in which girls wore borrowed dresses to avoid “the foolish pride that the rich feel toward the poor, and which draws the poor to imitate the desires and pleasures of the rich.”

While the first Tu B’Av at Bnos seems to have been observed decorously indoors, Sarah Schenirer later instituted celebrations of the holiday in a more natural, outdoor setting. In a newspaper report for the Bais Yaakov Journal, one student, Hodo Movshowitz, described how Tu B’av was observed in the resort town of Skawa, where Bais Yaakov held a summer program in 1932: through a nighttime hike up a path into the forest. “One hundred and fifteen of us go step by step, hand in hand, along the path, Mrs. Schenirer first among us, our hearts beating with extraordinary joy,” Movshowitz wrote.

According to Movshowitz’s report, a campfire was lit and the girls watched the flames in deep silence, until someone — a student — spoke of “the holiday that belongs to us, to young Jewish women,” her words echoed back by the trees. After another long silence, Schenirer, her face lit up in the firelight, began to speak: “And the fire upon the altar shall be kept burning thereby, it shall not go out.” She described the “secret place, the small and hidden flickering flame within each of us,” and that “many waters cannot extinguish love,” as the fire leapt and dry twigs flamed out in the grass.

After Schenirer finished speaking, the girls were so overcome with the urge to sing that, as Movshowitz wrote: “no power in the world could stop us.” They sang, the fire in their eyes growing more radiant. They added wood to the fire and the flames leapt up ever higher. As the night progressed and the flames glowed, the girls felt moved to get on their feet, and began to dance, hand in hand, with Schenirer among them, whirling until everything disappeared but the dance.

“The dancing lasts for a long, long time,” she wrote. “We dance as we accompany Mrs. Schenirer home, and only then do we ourselves go to sleep.”

Tu B’Av was indeed revived, but not only in the Zionist kibbutzim, and not only as a romantic ritual. Some leaders of Bnos saw the holiday as part of a larger effort to create a generation of observant wives and mothers who would keep their children on the Orthodox path.

But for Sarah Schenirer, the religious experience she was shaping had its own, less instrumental value: It wasn’t about who these girls would become, but who they already were, at that very moment around the campfire. What awakened those long-dormant sparks was the religious genius of a divorced woman, along with the girls who danced her home from the woods.

Correction: In the original headline of this article, the editor incorrectly referred to Tu B’Av, known as the Jewish Valentine’s Day, as a biblical holiday. It is not actually mentioned in the Torah, but originated in the Mishnah, rabbinic commentaries on the Torah.