Why The New York Times translated its Hasidic yeshiva investigation into Yiddish

The Gray Lady has likely never published an entire story in the language

The New York Times took the rare step of translating its investigation of Hasidic yeshivas into Yiddish by The New York Times

Sunday’s groundbreaking New York Times article about the dismal state of secular education in the Hasidic yeshivas in Brooklyn and the lower Hudson Valley elicited much heated discussion on social media. But it also drew interest for a very different reason: the investigation was published online in Yiddish as well.

Yiddish is the everyday language of around 700,000 Hasidic Jews globally, including large communities in New York, London, Antwerp and Jerusalem. Most families raise their children in the language, and it is the lingua franca of almost all Hasidic boys’ schools, although less so in schools run by the Chabad-Lubavitch community.

Translating the story into Yiddish was spearheaded by Michael LaForgia, an investigations editor for the Metro section, and Snigdha Koirala, deputy international editor for audience.

“Our reporting showed that many in the community did not speak English well, and we wanted them to be able to access the story,” LaForgia said.

“More broadly, we thought taking the time to translate it would underscore the reality of what we were doing: beginning a conversation and focusing attention on some of the least powerful members of this community.”

The Times reached out to the Forward three weeks ago seeking help finding a “highly experienced and sensitive” translator for what it described only as “an important story” of some length. The Forward provided a recommendation, but The Times would not confirm on Monday whom it had hired.

Although many commenters on Facebook and Twitter labeled this the first Yiddish article ever to appear in The New York Times, Koirala wasn’t able to verify that. One thing she knows for sure? “It’s the only one that we could find on our website.”

Several Times employees said on background that the Yiddish version of the article had garnered more readership than a typical English story in the Metropolitan section. One said it got more than 150,000 pageviews in the first 24 hours, though a Times spokeswoman declined to confirm that, saying the company does not release audience figures.

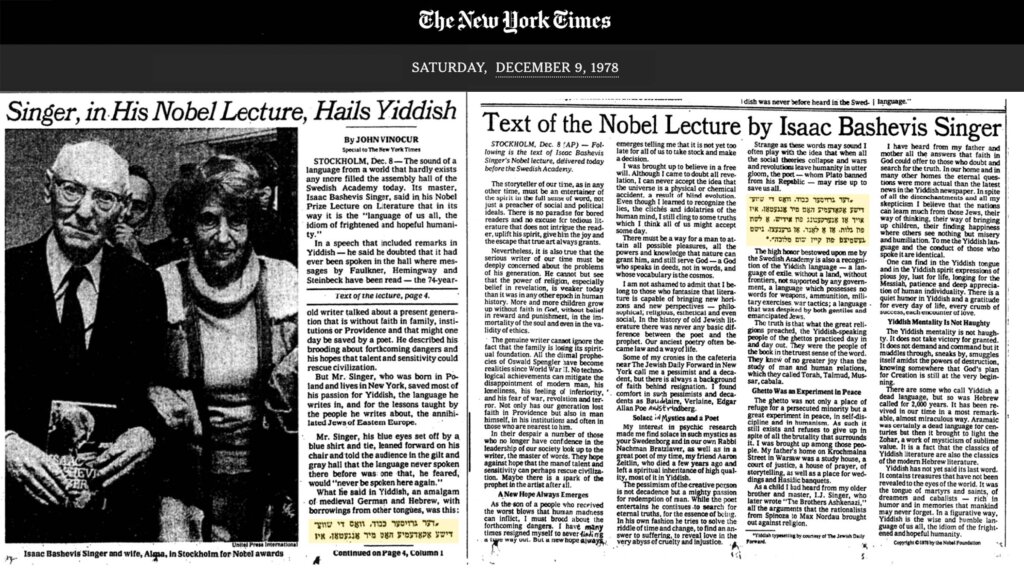

Eric Fettman, a noted historian of American journalism, pointed out that, although this may indeed be the first article published entirely in Yiddish, there was a precedent. On Dec. 9, 1978, the day after Isaac Bashevis Singer gave his Nobel Laureate speech, The Times published an article about his speech on the front page — including his introductory lines in Yiddish.

“The deep honor which the Swedish Academy has bestowed on me is also an acknowledgment of Yiddish, a language of the Diaspora, without a country, without borders, not supported by any state,” he said in his address.

Publishing content in different languages is not new for The Times. In addition to a daily report in Chinese and Spanish, the paper has translated investigations and special features into more than a dozen languages in the last three years, including French, Japanese, Burmese, Persian and Arabic.

For many Yiddish activists and academics of Yiddish studies, having a Yiddish article in The Times was exciting news indeed.

“I found it startling to see a Yiddish language article in The New York Times,” said Eddy Portnoy, academic advisor at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. “In consideration of the topic and the need to inform a particular target audience, I thought it was a brilliant move on their part, especially having had it translated into colloquial Hasidic Yiddish.”

Hasidic Yiddish differs from the standard Yiddish taught in most Yiddish courses today, both in respect to grammar and spelling, making it often challenging for Yiddish students to read. But it is the version of Yiddish most commonly spoken by Hasidic native speakers, and since the target audience for this translation was the Hasidic community, it made more sense to use a style that was familiar to them.

“The article marks a real step forward in giving Yiddish the same platform as other ‘major’ languages,” said Michael Wex, author of the bestseller, “Born to Kvetch.” “It also ensures that stories about the language community in question reach native speakers whose English might not be up to the demands of a lengthy article.”

Although Portnoy points out that The Times, as a secular newspaper, may be considered treyf (not kosher) in the Hasidic community, he hopes that this article will encourage at least a segment of the population to start reading it, adding: “I’m looking forward to more Yiddish material from the groye froy,” using the Yiddish translation for the newspaper’s nickname, the Gray Lady.