Eating Chinese meant proving that the shtetl had been left behind

A study done by two sociologists helps explain how this American Jewish tradition relates to fundamental issues of identity.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

I didn’t grow up with much awareness of Jewish tradition, but I knew that American Jews ate Chinese food on Christmas. Not all Jews, of course: but it’s widespread enough to feature prominently in jokes and cultural references, ranging from The Simpsons to Elena Kagan’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing.

And the association is not exclusively with Christmas: Chinese food plays an unexpectedly large role in the American Jewish psyche year round. As a kid living outside Boston in the 1970s and ‘80s, I had a vague sense that the Jewish attachment to Chinese food had connections to New York City, but I thought that was just because my parents grew up there. The reason often given for Jews eating in Chinese restaurants on Christmas is because historically they were the only restaurants open that day. There’s truth to this, of course. But a revealing article by two sociologists points out much deeper reasons for the cultural link between Jews and Chinese food generally — which sheds a clearer light on the particular association of this practice with Christmas.

The research meticulously explores the origin and persistence of the curious Jewish attachment to Chinese food. The study was conducted by Gaye Tuchman of the University of Connecticut (now emerita) and Harry G. Levine of Queens College and the City University of New York Graduate Center. But because their work appeared in an academic ethnography journal, with a sole reprint in an expensive textbook about ethnic foods, it hasn’t reached the wider public or contributed the way it should to discussions of this intriguing American phenomenon.

The Jewish love affair with Chinese food

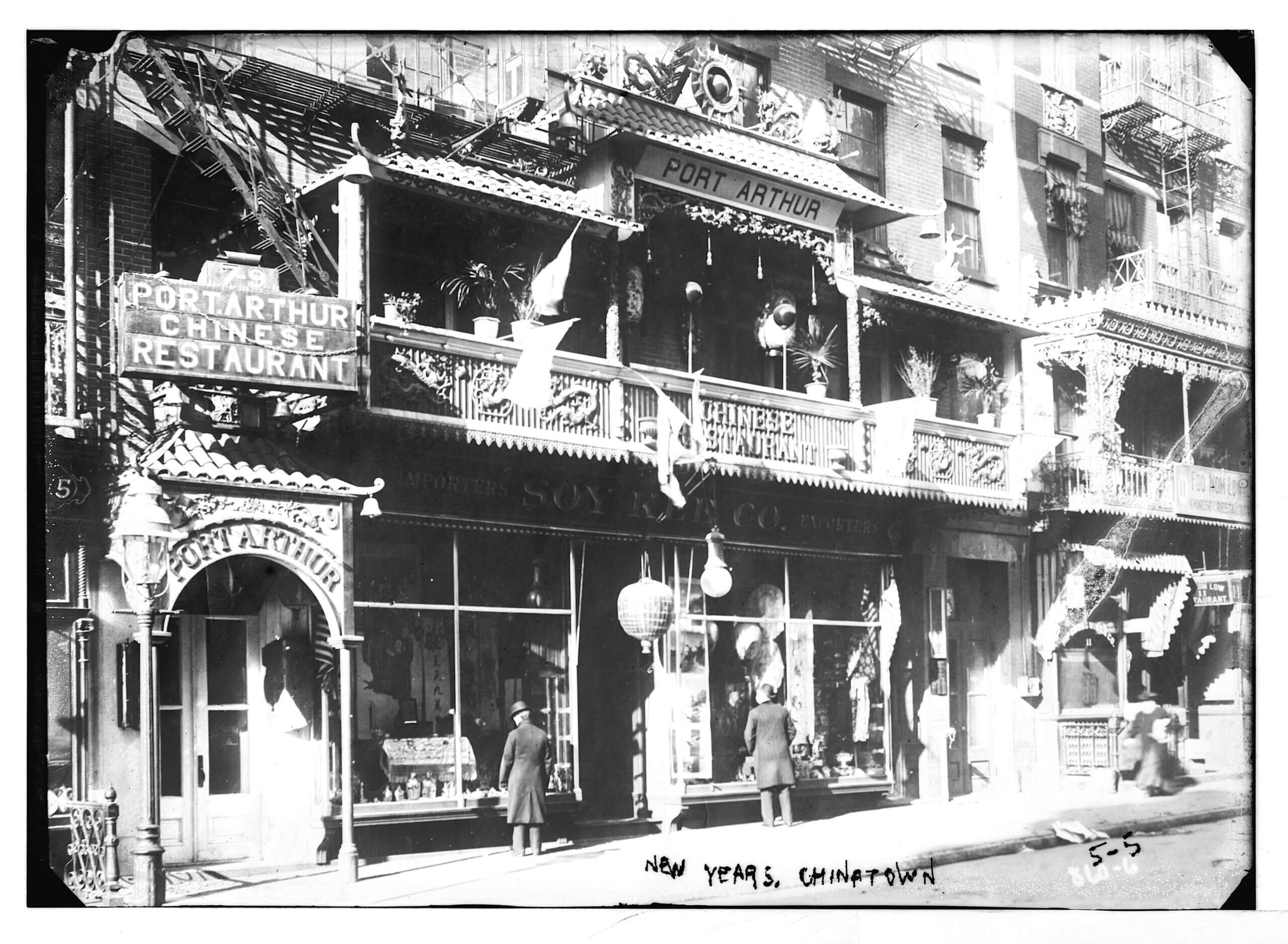

Tuchman and Levine don’t focus on Christmas in their article. They’re interested in the Jewish love affair with Chinese restaurant food more broadly, especially in New York during the first three decades of the 20th century. But the leap from love of Chinese food generally to the choice of this cuisine on Christmas is not a long one.

The authors’ most basic point is that Chinese cuisine, though generally not kosher, felt unthreatening to Jewish immigrants accustomed to kashrut who gradually became more flexible about their eating choices in America. Chinese food was “safe treyf” (the authors’ coinage): Like kosher food, it doesn’t mix meat and milk — in fact, it rarely uses dairy products at all. Of course it does rely heavily on pork and on shellfish. But in most dishes served in New York restaurants in the earlier 20th century, these forbidden ingredients were so finely chopped that they became invisible — and thus ignorable. Jewish diners knew they were eating things they shouldn’t, but they couldn’t see them or even really taste them as separate flavors. Everything blended together into a deliciously minced whole.

Why not Italian food?

This was emphatically not the case in other types of ethnic restaurants, such as Italian — where pork and unkosher veal and chicken are often served as cutlets, frequently combined with cheese or a dairy-based gravy. Immigrant Jews who had been in New York for a while, and especially their more Americanized children, could eat dairy-free chopped pork and shellfish in a Chinese restaurant with a minimum of guilt.

But what were Jews doing in Chinese restaurants at all? Italian immigrants who ate out generally chose Italian food — but according to the authors, Jewish diners actually prioritized Chinese food over their own cuisine. A powerful reason was the association between Chinese restaurant dining and cosmopolitan sophistication. Eating at a Jewish delicatessen was the kind of thing a greenhorn would do. Eating Chinese meant trying something new, proving to oneself and others that the shtetl had truly been left behind.

Jewish immigrants arrived in America fairly urbanized and comparatively open to new experiences, and with a compulsive need to internalize their adopted American culture. Jews, unlike many other immigrants, rarely went back to their country of origin, where religious, social and economic discrimination had made their lives unsustainable. They urgently wanted to be Americans, be sophisticated, prove they had what it took to make it in this new world. Chinese restaurant food helped confirm and solidify this new identity.

A sense of having ‘arrived’

A related factor was that Jewish cuisine in America never really developed a “fancy” persona with tablecloths and silverware — so eating in a Chinese restaurant that provided these things gave Jews a sense of having “arrived.” The food was reasonably priced, but the formal atmosphere felt like a step up.

The authors also point out that Chinese restaurants — unlike the Italian restaurants that Jews had access to on the Lower East Side — rarely or never displayed openly Christian symbols or decorations. Many Italian eateries proudly displayed images of Jesus, the Virgin Mary and the saints — figures which Jews knew all too well and often, with good reason, feared. The decor in Chinese restaurants was excitingly “exotic,” but had no threatening associations for Jews. Chinese calligraphy, which often features prominently in its art and ornament, was also something that Jews — with their own history of reverence for written texts and beautiful script — could appreciate.

Sadly, anti-Chinese racism was an additional reason. Jews had long been accustomed to feeling like the lowest of the low, but in America, they were generally held in somewhat higher repute than the much-maligned Chinese — whose fine restaurants were appreciated, but whose culture in general was treated dismissively. In a Chinese eatery, Jews didn’t need to fear the judgment of waiters and fellow guests whose social status was sadly even lower than their own.

Powerful nostalgia for descendants of Jewish immigrants

Over time, eating Chinese became intensely associated with Jewishness — first in New York City, and then in other American locales. No wonder Chinese food is associated with Christmas. Its powerful nostalgia for the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Jewish immigrants gives it a delightfully Jewish “tam” (taste — in every sense) on a day when Christian society leaves Jews feeling excluded. Chinese restaurants today, even if their owners are Christians, still rarely display any kind of Christian imagery.

Eating Chinese rather than Jewish food on Christmas may also be a more ironic version of our forebears’ craving for sophistication. By going to a Chinese restaurant, Jews are essentially saying that although Christians may reject us on Christmas, we are American enough to respond by showing our appreciation of someone else’s culture. For reasons historical and contemporary, nostalgic and self-affirming, eating Chinese food remains a perfect expression of American Jewish identity on Dec. 25.