The myth and songs inspired by the Jewish couple that perished in the Titanic

The Yiddish music written in memory of Isidor and Ida Straus reveals the empathy that Jews had for them

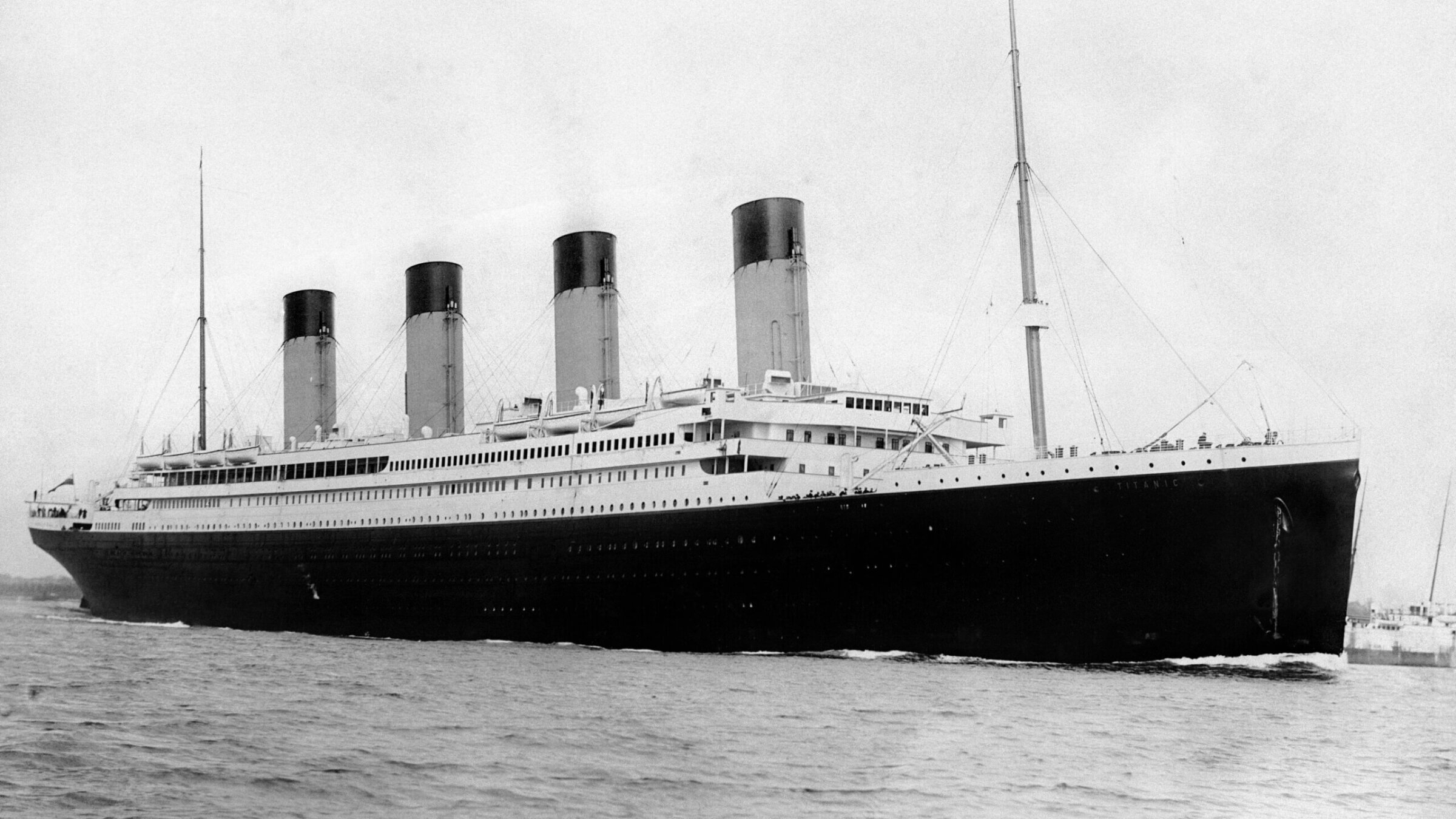

The RMS Titanic Photo by Wikimedia Commons

In the cold, early hours of April 15, 1912, the new White Star liner RMS Titanic — the largest and most luxurious passenger vessel in the world — disappeared beneath the strangely still surface of the North Atlantic, less than three hours after striking an iceberg. She took with her more than 1,500 lives.

There were many Jewish passengers on Titanic’s maiden voyage. Although the true number is now irrecoverable, estimates range from several dozen to well over a hundred. Many were immigrants traveling in steerage (including a female survivor who was probably a distant cousin of this writer), where the White Star line — catering to the lucrative immigrant trade — even offered a kosher kitchen. They, like most steerage passengers, attracted little notice at the time, even though the Titanic’s steerage death toll was appalling.

There were also well-known Jewish names aboard. Wealthy 46-year-old businessman Benjamin Guggenheim (brother of Simon Guggenheim, then Senator from Colorado) had a playboy reputation; he was traveling first class with his mistress (who was saved). He and his valet attracted favorable press when survivors reported that they had dressed in their evening best, “prepared to go down like gentlemen.” Guggenheim asked that his wife (not aboard) be informed that he had done his best to do his duty.

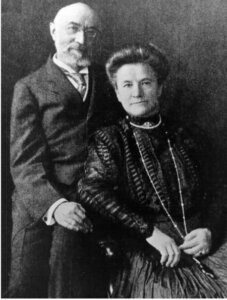

But it was a Jewish couple, Isidor and Ida Straus, who truly became Titanic legends — from the very start. Isidor, a very prominent businessman, was born in Bavaria in 1845 and emigrated to the United States as a child, first living in Georgia (where he actively supported the Confederacy in the Civil War) before ultimately settling in New York. With his brother Nathan, Straus became co-owner of Macy’s department store, and was active in Democratic party politics. He married Ida Blun (born 1849 in Worms, Germany) in 1871. They were by all accounts an especially devoted couple, with seven children, of whom six survived to adulthood. Both were active in philanthropic causes, including assistance for new Jewish immigrants.

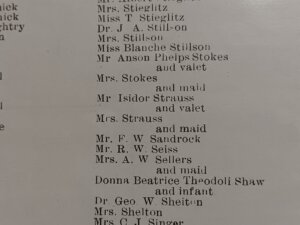

The Strauses sailed from New York for the South of France in January 1912 aboard the Cunard liner Caronia, together with Ida’s maid and Isidor’s valet. This writer has an onboard newspaper from that voyage, with the Strauses listed among the first-class passengers. Ironically, four months later, Caronia was the first ship to send Titanic one of many fruitless warnings of ice.

After visiting their native Germany, the Strauses were ready to return in April. With Atlantic sailings limited by a coal strike in England, they opted for an opulent first-class suite on Titanic’s first crossing.

During the sinking, as it became clear the ship and its passengers were in serious danger, Ida put her maid, Ellen Bird, in a lifeboat and gave Bird her fur coat — but Ida refused to board the lifeboat if it meant leaving Isidor behind. According to multiple witnesses, she insisted to Isidor that after all their years together, where he went she too would go. Other passengers suggested (probably wrongly) that the officers would not object to an elderly gentleman like Straus joining his wife in a boat. But Isidor dismissed the idea; he would not accept special treatment before other men. Isidor, Ida, and Isidor’s valet John Farthing all perished in the disaster. Isidor’s body was recovered during the later search for remains, and was buried that May in the Bronx. Ida’s body was never found.

The Forward showed immediate interest in the Straus story, even though the Strauses were established German Jews, not more recently arrived Yiddish speakers like most of the paper’s readership — and relations between the two groups could sometimes be strained. The Forward’s April 16 editorial on the larger meaning of the disaster for human progress dwelt on the shock of the catastrophe: “What floods the reader from the news reporting is that human emotion of sympathy.”

On the 18th, editor-in-chief Ab Cahan’s furious Forward editorial urged readers to look beyond the inevitable sense of mourning to the capitalist greed that led to the Titanic and a litany of other avoidable disasters, “from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, to the train accident, to the mine explosions, to the consumption plague and all sorts of carnage.” But while demanding culpability for reckless and greedy owners, Cahan didn’t deny that “sympathy and pain… dominate the soul.”

As updates trickled in from the rescue ship Carpathia’s overburdened wireless operator, it quickly became clear that neither Straus had been saved. Only four women from first class were lost. Like the English-language press — which also took immediate interest in the prominent and well-known Strauses — the Forward quickly surmised that Ida must have refused to leave her husband. On April 16, the paper reported that “apparently Mrs. Straus did not want to part from her husband and did not use the opportunity to save herself.”

On the 17th, the Forward declared it “the general opinion” that Ida “preferred to choose death rather than leave her husband on the threshold of a watery grave.” The story grew in power and interest as Carpathia docked in New York on April 18 and actual witnesses to the Straus drama could speak to the press. In fact, far more people would soon claim to have witnessed their already famous moment on the boat deck than could possibly have done so — but reliable accounts confirmed the details. Interest began to shift from the wealthy and prominent Isidor to the romantic figure of Ida.

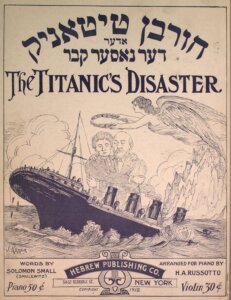

A legend had been born, in both Yiddish and English-speaking mass culture. Soon, Yiddish songs were published in honor of the couple. Among them is “The Titanic Disaster, or The Watery Grave,” by singer, composer, and lyricist Solomon Smulewitz. The sheet music, although issued by New York’s Hebrew Publishing Company, credits his anglicized name, Solomon Small, with his original name beneath it in parentheses.

The sheet music’s elaborate cover artwork depicts the embracing couple rising ghost-like above the sinking ship as a hovering angel crowns them with laurel. Smulewitz’s sentimental Yiddish lyrics dwell at length on the futility of man’s pretensions against the sea — yet culminate in the triumph of a woman’s soul crying out: “‘I will not leave this place, / I die here with my husband.’ / Small and great should honor / the name of Ida Straus.”

Another Yiddish song about the disaster, “Song of the Titanic,” has been recorded twice by well-known artists: one by Mandy Patinkin in his 1998 album “Mamaloshen” and another by Lorin Sklamberg in his 2022 album “Helsinki Yiddish Cabaret.”

And the legend of Titanic’s most famous Jewish story lives on. Practically every dramatization of the Titanic tragedy — including A Night to Remember (1958), James Cameron’s Titanic (1997), and the Broadway musical Titanic (1997) — featured the Strauses. In 2005, Cameron brought nimble remote camera vehicles to the Titanic wreck in the North Atlantic. One of his top priorities was to enter and film the ruin of the Strauses’ C-Deck suite. To his uncontainable excitement, his remotely operated vehicle filmed the still-gilded ornamental clock in their suite’s sitting room, half-buried in silt yet nearly intact, still in place atop the remains of the fireplace mantel — just where the devoted couple once consulted it before disaster struck.

One cannot help but wonder: When Isidor refused to even seek a place in a lifeboat, was he thinking, at least in part, of the harm he could do to his fellow Jews if he survived and was seen as a coward, a sneak, a thief of a woman’s place in a boat?

Soon after their deaths, their adopted city of New York renamed a park in their honor at 106th Street and Broadway, near the couple’s home. A public subscription raised $20,000 for a granite and bronze memorial. Its inscription, taken from the Biblical passage in which David mourns King Saul and his son Jonathan immediately after their deaths in battle, honors Ida’s refusal to be parted from her husband and the nobility of the couple’s ending: “Lovely and pleasant were they in their lives, and in their death they were not divided.”

The memorial sculpture depicts the figure of Memory, gazing over a reflecting pool, contemplating, as both Smulewitz’s song and the Forward put it, the couple’s “watery grave.” Yet both Isidor and Ida may have been mindful not only of their love for each other, but of the impact their actions might have — not only on their own memory, but on the honor and reputation of the Jewish people for whom both had labored.

Several Yiddish source materials for this piece were translated by Jennifer Stern.