The art teacher who inspired Marc Chagall to paint Jewish men and women

Yehuda Pen showed his students that a specifically Jewish “fine” art was both possible and desirable.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Chances are that most readers have never heard of the painter Yehuda Pen (1854-1937). That’s surprising, considering that it was he who influenced Marc Chagall to create paintings depicting traditional Jewish life.

Pen was a casualty of the fame of his students, who also included El Lissitzky and Solomon Yudovin. Yet, as an artist and teacher, Pen was instrumental in creating a distinctly Jewish form of art that would explode in a thousand directions during the 20th century. In most cases, including Chagall’s, Pen was his students’ first teacher. Often he was the first artist they had ever met. He introduced them to the potential of specifically Jewish art at the most formative moment in their young lives. The seeds he planted bore remarkable fruit.

Artistically, Pen had little in common with his future superstar pupils: he worked throughout his career in a conservative realistic style that his students came to reject. But his art was deeply infused with Jewishness in a way that hadn’t been seen before in the Pale of Settlement.

Pen was a trained painter with the same qualifications as many of his Russian contemporaries — but he focused almost exclusively on Jewish themes. Through the example of his work and life, he showed his students that a specifically Jewish “fine” art was both possible and desirable. When his students made the stylistic leap into modernism, they took this Jewish consciousness with them.

Sketching portraits in cheder

Pen was born into a deeply religious family in Novo-Aleksandrovsk (now Zarasai), Lithuania in 1854. He was fascinated with drawing from early childhood, and spent much of his time in the cheder sketching portraits of his fellow pupils — who paid him with buttons that he traded in for pencils and paper. His widowed mother was horrified by his penchant for drawing, calling his portraits “idolatrous” and trying to beat the taste for art out of him.

But Pen couldn’t resist the impulse to draw. With the encouragement of a Jewish art student whom he met while apprenticed to a Hasidic sign-painter, he set his sights on the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. After overcoming many challenges, he was finally admitted as one of the handful of Jewish students at the prestigious Academy. He obtained a degree and a Silver Medal in 1885, making him one of a tiny number of qualified Jewish academicians.

After an unsatisfying job as a private painter to a minor nobleman, Pen was invited to settle and practice in the Belarussian town of Vitebsk. Vitebsk had a substantial Jewish population and was rather culturally sophisticated for a provincial city. But it had very few practicing artists — and both the Jewish residents and the town’s Russian governor wanted to put their home on the artistic map. Pen’s status as an Academy graduate gave him prestige, and he was offered a large combined apartment and studio on one of the town’s main streets.

Listen to That Jewish News Show, a smart and thoughtful look at the week in Jewish news from the journalists at the Forward, now available on Apple and Spotify:

Painting everyday Jews

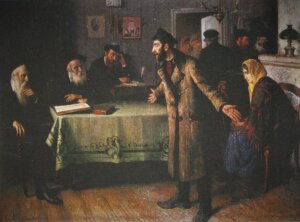

Once he was free to pursue his own interests, he turned almost exclusively toward Jewish subject matter. And unlike some Russian Jewish artists such as Isaac Asknazi, Pen didn’t emphasize subjects drawn from the Hebrew Bible, which were equally palatable to Christians. Instead he showed Jews as he knew them: ordinary men and women engaged in their daily work and religious rituals.

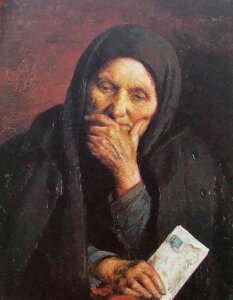

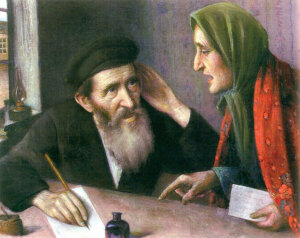

His 1903 painting Letter from America was characteristic: it depicted an elderly Jewish woman (possibly the artist’s pious mother) thoughtfully contemplating a letter she had received from family in America. He also portrayed an old couple struggling to communicate as they composed a letter to relatives in America.

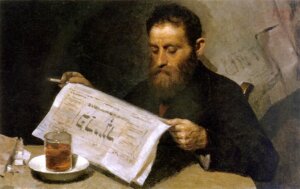

In other works, Pen showed a grizzled tailor in a skullcap and tallis laboriously ironing a garment; a clockmaker with a skullcap surrounded by the delicate tools of his trade; a woman with a shawl over her head, engrossed in a religious text (probably the Tsene-rene) at home on Shabbos; a frail dressmaker with a tallis under his vest sewing a garment; a man with a cigarette and a glass of tea perusing the Yiddish newspaper Der Fraynd; an old bedridden woman clasping her hands in prayer on the Sabbath as she prepares to die — and many more.

The Jewish life he depicted was vanishing

Some of Pen’s Jews were elderly and careworn, shown living traditional lives shaped by Jewish rituals; others reflected a more modern, youthful sensibility. His gentle realist style and subdued color palette, influenced by the Dutch Golden Age painters he had come to admire in St. Petersburg, sensitively captured wrinkled faces and hands, as well as the gleam of tools and the texture of fabrics.

These were humble folk, but Pen infused them with deep dignity as they went about their labors and performed Jewish rituals in their modest workshops and homes. Even when they were shown working rather than reading or praying, a sense of the sacred permeated these canvases: the antiquity and moral weight of Jewish tradition were always a palpable presence.

Of course Pen was very aware that the Jewish life he depicted was rapidly vanishing under the intense pressures of modernization and secularization — not to mention war, pogroms, economic upheaval and mass emigration. Indeed, it was because this world was disappearing that capturing it on canvas was so essential. Pen shared this impulse with Yiddish authors such as Sholem Aleichem (whose works he read avidly) and Y.L. Peretz, who strove to create a “modern” Jewish culture that would also preserve and honor the traditional customs of ordinary Jews.

Pen was singled out for praise in this regard by S. An-ski, author of The Dybbuk (itself both radically innovative and intertwined with Jewish folk life) and leader of an ethnographic expedition documenting Jewish folk life in the Pale of Settlement. An-ski likely understood that Pen was no stylistic innovator (he wrote about Pen in 1912 when modernism was well established) — but he recognized that the very act of creating profoundly Jewish visual art was itself revolutionary.

The only Jewish art school in the Pale of Settlement

Pen began passing on this radical understanding of Jewish art to his students when he opened his own art school in Vitebsk in 1897: the first and for a time the only school of art run by and almost exclusively for Jews in the Pale of Settlement. Thanks to financial support from a wealthy Vitebsk beer brewer, those who were too poor to pay were admitted without charge. Instruction was in Yiddish rather than Russian since so many students knew only Yiddish, and no classes took place on the Sabbath. (Pen remained religiously observant throughout his life.)

The vast majority of his students were male Jewish teenagers, though he did have several female pupils. He taught them a true appreciation of the very concept of art: a revelation and a gift to young people from traditional homes where the fine arts were usually not understood or valued. His large studio, which doubled as the school, was lined floor to ceiling with paintings. Students described his deep veneration for beauty and craftsmanship: and his most famous pupils all became excellent artists from a technical standpoint, proving the effectiveness of his teaching.

Many of Pen’s students maintained an affectionate correspondence with him for the rest of their teacher’s life. When Chagall was living in Paris, he wrote to Pen frequently. He once movingly recalled the first time he spotted the blue and white sign for Pen’s art school while traveling on the tram in Vitebsk at age 19, and his excited trepidation when he convinced his mother to let him enroll there as a pupil.

Chagall hired Pen in his own art school

Tellingly, Chagall painted Pen’s portrait (sadly this has been lost), and Pen painted a striking portrait of Chagall — probably his finest work. When Chagall opened his own People’s Art School in Vitebsk in 1918, he invited Pen to become one of its teachers. The two men had long since parted ways stylistically, but Chagall still wanted his old mentor to play a role in his new academy. Many of Chagall’s students had previously studied at Pen’s school.

Pen taught his students how to look at, think about and make art: but ultimately his reverence for Jewishness was his most crucial legacy. It’s no coincidence that Chagall became the quintessential Jewish artist of the 20th century. El Lissitzky also engaged intensively with Jewish imagery in his earlier career. Lissitzky in turn worked with Issachar Ber Ryback, another very significant Jewish artist who remained faithful to Jewish themes throughout his short life.

Another artist, Solomon Yudovin, also overwhelmingly portrayed Jewish subjects in his graphic works, as did some of Pen’s lesser-known students, Abel Pann and Lev Zevin. Without Pen, would any of these artists have become Jewish artists? A strong case can be made that they would not.

Pen’s murder horrified his students

In shocking contrast to his gentleness as a man, artist and teacher, Pen’s life ended violently in February 1937. For reasons that remain unclear, he was butchered with an ax in his studio-apartment — the very place where he had worked and taught — at the age of 82. 1937 was the height of Stalin’s Great Purge, and it seems likely that the murder was connected to this: though why Pen, of all people, was targeted has eluded historians. Was it because he was in contact with former students living abroad? Because he was considering displaying some of his own works in the West? Pen’s devoted students were horrified by his fate: Chagall wrote a poetic tribute to and lament over “the Old Rebbe,” as he called him, as well as deeply felt letters to Pen’s family.

A few scholars of Jewish art have pushed in recent years for greater recognition of Pen’s significance, both as a teacher and as the first truly Jewish artist in the Pale of Settlement. It’s unfortunate that his conservative style has disguised his revolutionary contribution, and that the fame of Chagall and his other students has thrown his own role into shadow. But without Pen, there might never have been modern Jewish art. As Chagall wrote to Pen in a letter: “You have trained a vast generation of Jewish artists.” Anyone who appreciates the creative genius of that vast generation and the generations that followed is — without knowing it — paying tribute to Yehuda Pen.