Online ‘zine’ unites young Yiddishists

Yiddish activist Sarah Biskowitz and Yiddish TikTok star Cameron Bernstein are building a home for new voices through ‘Yiddishistke’

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Zines are limited-run, self-produced magazines associated with punk rock, pieced together with poetry, art, a copy machine and an anarchistic attitude.

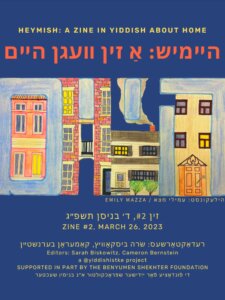

A new Yiddish zine called Heymish: A Zine about Home has many but not all of these elements. (No signs of Xeroxing or the messiness in formatting commonly seen in punk zines.) The publication was put together by recent college graduates Sarah Biskowitz and Cameron Bernstein through their Yiddishistke Instagram account, which has more than 5,000 followers.

Their attitude, however, is “punk rock.” The zine gives a platform to writers and artists who might not otherwise get published or feel comfortable submitting to the few Yiddish publications that already exist. As Biskowitz put it in an interview with the Forverts, it’s a publication “by Yiddish learners for Yiddish learners.” All levels of Yiddish proficiency and experience were represented, from a few sentences from beginner students to poetry written at the level of a literary journal. It was edited by Yiddish studies Ph.D. candidate Sandra Chiritescu, with some poetry edited by Yiddish textbook co-author Mikhl Yashinsky.

The zine, which was launched March 26, is an anthology of international participation in Yiddish culture: a 71-page collection of 26 essays, poetry, art and even a comic.

Inspired by the call for submissions

The Yiddishistke account put out a call for submissions in late 2020. Many of those who responded were fellow students. But not just students — Bernstein’s former professor at the University of Chicago Jessica Kirzane tweeted that they inspired her to write in Yiddish for the first time for publication in the zine.

Others who submitted from around the world only knew them from the Instagram account, which was, until recently, anonymous. Bernstein, who designed the zine, has a significant TikTok following, but many of those who submitted did not realize she was behind the account.

Heymish is the second and likely final zine put out by Yiddishistke, the first being Di Goldene Keyt Geyt Vayter (The golden chain of tradition goes on), a series of illustrated translations of Avrom Sutzkever’s poetry. It was the last project that the now-defunct Benyumen Shekhter Foundation financially supported. Aside from the difficulties of finding money to compensate editors’ and their own efforts, Biskowitz and Bernstein have less time on their hands than before; Bernstein is attending medical school in Australia, and Biskowitz is studying Jewish texts at the Pardes Institute in Israel.

What is ‘Heymish’?

“The goal was to pull together the global Yiddish community, that’s what we were brainstorming for,” Bernstein said. They were looking for “a fruitful theme to get people to engage and submit to the project,” no matter their background.

Yiddishistke asked for submissions about the word “heymish,” which conjures up many different but related meanings. Literally, it means homey, but it could be interpreted to mean cozy, familiar or mildly chaotic among other things.

More importantly to the zine’s creators, it reinforces the concept of Yiddish as home. Biskowitz said that among Hasidim, the word simply means “Hasidic.” And just as the word connotes a sense of belonging in the global Hasidic community, the internet has endowed the term with a sense of belonging in the Yiddish community.

A common theme in the submissions was that Yiddish brings people together even when they are in so many different places, and especially when they feel alienated from their surroundings.

Tamara Gleason Freidberg, a Mexican-born doctoral student in London, wrote about feeling like a stranger in both the U.K. and when she visits Mexico after having acculturated to some degree to British life. “Heymish,” she wrote, is the feeling she gets “when I hear a group of people speaking Spanish or Yiddish.” Satoko Kamoshida, a Japanese Yiddish teacher and linguist in Tokyo, wrote that Yiddish has become her home and has helped her feel like herself.

‘The people I come from are gone’

Divyam Chaim Bernstein, a British artist, drew a comic about finding her ancestors and her place among them, reflecting on how their lives in Eastern Europe seem so distant from hers in London. Nonetheless, she writes in a panel in her comic that “the people I come from are gone. The places, the worlds they lived in have vanished. And yet something is very much alive, like a warm fire burning at the heart of an old forest.” Yiddish, though an old world, is still alive and is her home.

There are other, more complex topics and emotions broached in the zine. One poem described the frustration of being stuck at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, another about the comforts of walking around the neighborhood at night.

Then there is the broader ideological concept of Yiddishistke. “The Yiddish language has often been seen as a domestic, feminized language,” wrote the creators in their introduction. Rivke Margolis, a Yiddish scholar at Monash University in Australia, said Yiddish was once only supposed to be read by women or illiterate men, and was seen as shameful.

“As young feminist Yiddishists, we want to both honor and push beyond this characterization of Yiddish by using it to explore what ‘heymish’ means to Yiddishists around the world.” This means taking this marginalization and using it to define Yiddish as inclusive as a language and culture, capable of taking anybody from wherever they are, and standing up for social justice.

The zine has been received positively by Yiddish teachers and scholars, who are using it to teach the language and analyze its modern culture. At the Yiddish Language Structures conference in London in March, Margolis made the zine part of her presentation on the cultural continuity of Yiddish.