How Yiddish became a ‘foreign language’ in Israel despite being spoken there since the 1400s

The exhibit ‘Palestinian Yiddish’ chronicles the integration of Yiddish with Arabic, its literary rise and violent suppression in pre-state Israel

The “Arabic-Yiddish Teacher” was the first text created for Yiddish-speaking students of Arabic. The book’s cover is incorporated into YIVO’s exhibit poster. Courtesy of YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

It’s 1945, three years before the establishment of the state of Israel and at the very end of the Holocaust.

Vilna Ghetto fighter Rozka Korczak-Marla comes to Tel Aviv, addressing the assembled in Yiddish about the extermination of Eastern European Jews.

David Ben-Gurion, who would soon become Israel’s first Prime Minister, then spoke to the crowd in Hebrew. “A comrade has just now spoken here in a grating, foreign language,” he declared.

Ben-Gurion’s shocking remark was part of a pattern of denigration expressed by advocates of Modern Hebrew within the Zionist movement during the pre-state years. It aimed to delegitimize the Yiddish language using violence, intimidation and propaganda.

A year after its establishment in 1948, the state of Israel banned Yiddish theater and periodicals under their legal powers to control material published and presented in foreign languages (with the important exception of poet Avrom Sutkever’s literary magazine Di goldene kayt). This firmly shut out the language and its supporters from cultural legitimacy from then on, even after the heaviest of restrictions were lifted some years later.

It was no guarantee that Modern Hebrew would become the victor in Mandatory Palestine’s language wars. After all, Yiddish was the first language of the waves of Jews who began migrating to the Land beginning in the 1880s. In fact, Yiddish was continuously spoken in the Land going back to the 15th century.

The exhibit Palestinian Yiddish: A Look at Yiddish in the Land of Israel Before 1948, curated by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City, gives us glimpses of this deeper story of Yiddish in the Land of Israel, from its first years in the 1400s to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, with the visual aid of artifacts and pictures rarely seen by the public.

A brief history of Ashkenazi immigration

Ashkenazis had been settling in the Holy Land since at least the 15th century.

The well-known commentator on the Mishnah, Rabbi Ovadiah Bartenura, documented their presence in letters he sent to his brother from 1488 to 1490, and noted that they were treated harshly and dwindled in number over time under the ruling Mamluk Sultanate.

The preponderance of immigration to the Holy Land came from exiled Sephardic Jews, beginning in 1492. Their wealth and connections within the Ottoman Empire allowed Jews to be treated much better than they had been under the Mamluks, whom the Ottomans conquered in 1517, placing the Holy Land under Ottoman control.

Ashkenazi immigrants to Ottoman-controlled Palestine came in waves over the centuries. The first mass migration occurred under the leadership of Rabbi Yehuda HeHasid, who led an influx of Jews from Poland in 1700. Then came Hasidim and their opponents, the Misnagdim, in the late 18th and early 19th century, and newer Jewish communities, like Mishkanot Sha’ananim located outside of the walls of Jerusalem and the settlement of Petah Tikva in the mid-to-late-19th century.

A ‘yidishe mame’ in 16th-century Jerusalem

Among themselves, Ashkenazi Jews spoke and wrote in Yiddish. The first evidence of written Yiddish in the Land can be seen in the exhibit on loan from the Cambridge University Library. It dates from 1567.

“The first document that I show in the exhibit,” said Eddy Portnoy, Director of Exhibitions at YIVO, “is a fragment of a letter written by a woman in Jerusalem to her son in Cairo in Yiddish.” It was one of several such letters found in the collection of Jewish manuscripts called the Cairo Geniza, another one of which had almost stereotypical yidishe flourishes to it.

“One of them has her telling him that he should come back to Jerusalem, that he won’t have a good life in Cairo, that there’s work available for him in Jerusalem if he wants to come back. She wonders why he doesn’t write to her enough,” Portnoy said.

‘Allah karim, got vet helfn!’

Though the Holy Land was under the control of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, the dominant local culture was Arabic. Yiddish developed, as it does in every country, integrating the dominant local language.

In 1966, Vilna-born Yiddish language scholar Mordechai Kosover wrote about the history of the Old Yishuv, those Jews who immigrated to Israel before 1880, and its particular dialect of Yiddish in a book called Arabic Elements in Palestinian Yiddish, which is prominently featured in YIVO’s exhibit. “We have a little section where I provide ten examples of Arabic that were integrated into the Yiddish of the Old Yishuv and they’re all taken from Kosover’s book,” said Portnoy.

Kosover divides the linguistic parts of the book into sections on how words were changed, thanks to the influence of Arabic, and common sayings in Yiddish that used Palestinian Arabic.

For example, Allah karim, meaning “God is generous” in Arabic, is used more earnestly in Yiddish as Allah karim, got vet helfn! (God will help!) Ottoman Turkish words that entered Arabic also made it into Yiddish: kalabalık (pronounced “kalabaluk”), meaning “crowd,” was used in the phrase es iz a gantzer kalbelik, meaning “a whole crowd is there.”

While Rabbinic Hebrew was spoken between Jews of different Jewish communities, Yiddish was spoken at the marketplace with the Arabs. In fact, many Arab families spoke or at least understood Yiddish well into the 20th century.

‘Er iz a baladi’

From the 1880s to the 1920s, three increasingly intense outbreaks of anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire killed tens of thousands of Jews. This spurred Jews into action in a variety of ways.

By 1924, 2 million Jews had emigrated to the United States. Thousands joined the workers’ movement called the Jewish Labor Bund, while others joined the Bolsheviks. Hundreds of thousands joined the ranks of the Zionists, who themselves were divided into many factions.

Zionism, the idea that there must be a national homeland for the Jews, was ultimately rooted in two ideas promoted by Zionist thinker Theodor Herzl: Antisemitism was inevitable, and Jews around the world must unite in a land they would build together.

Though this was ostensibly a political solution to a political problem, there was also a cultural element: Diaspora was not just a political situation to be resolved, but a cultural morass to be purged. When the Zionist movement Bilu began bringing Ashkenazi immigrants from the Russian Empire to the Holy Land to create kibbutzim, agricultural collectives, and when Eliezer Ben-Yehuda led a movement to revive Hebrew in Jerusalem, these were accepted as core elements of Zionism.

Yiddish began to represent diaspora and feebleness, said linguist Ghil’ad Zuckermann. “And Zionists wanted to be Dionysian: wild, strong, muscular and independent.”

The members of the first three Aliyot, Zionist immigrations to the Holy Land during the time of the pogroms, were more secular than the Ashkenazim who came before them and more ideologically motivated to start a Jewish state. They also exceedingly outnumbered the religious Jews.

The Jews of the Old Yishuv begin to see this as an affront to their religious beliefs. “They also saw these foreigners in fine clothes publishing in Hebrew, living in mixed kibbutzim; it was seen as destabilizing and they saw it as an end of their way of life,” said graduate student Eyshe Beirich.

The Old Yishuv Palestinian Yiddish speakers added a word to distinguish themselves from the newcomers. Er iz a baladi, meant “he is one of us,” with the word “baladi” meaning “native-born” in Arabic. The Hebrew word khalutz, or “pioneer,” meant “one of them.”

Hebrew fanatics

After the Ottoman Empire was defeated in World War I, it collapsed, eventually giving up the Holy Land to Britain in what would become Mandatory Palestine. Around that time, a curious textbook appeared. Egyptologist Getzel Selikovitsch published a Palestinian Arabic textbook in Yiddish, which is featured in the exhibit. Its stated aim was to help the Jewish Legion of the British Army speak to Palestinian Arabs. The Jewish Legion, an internationally recruited force, had fought the Ottomans in the Middle East.

Working its way through simple phrases, the textbook eventually teaches the reader how to say more complex phrases with political overtones like “Lord Reading, English ambassador in Washington, is a great speaker and a wonderful Jew,” and “the Jewish soldiers in the Holy Land have great glory.”

The Jewish Legion was formative for many Zionist leaders, including Ben-Gurion, who were motivated to bring the Holy Land under British control. The British Balfour Declaration of 1917 declared Palestine to be a national home for the Jewish people, and Zionists hoped that with Britain in charge, the state of Israel could be established.

Yiddish and Arabic proved to be vital tools for settling the Land. Zionists also used Yiddish abroad for propaganda purposes (the first political speech in Yiddish ever filmed was given in 1934 by Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky in Paris). But the movement for Hebrew domination in the Land of Israel was strident.

The Herzliya Gymnasium in Tel Aviv, the first high school in Palestine with courses taught entirely in Hebrew, became the hotbed of intense Hebrew activism. The activism began in 1913 when students pressured the newly founded science and engineering university, the Technion, to teach in Hebrew rather than in German.

Portnoy relates that in 1914, the political thinker Chaim Zhitlowsky came to Palestine, giving his lectures in Jerusalem, Haifa and other places in Yiddish, following the footsteps of writer Sholem Asch, who gave lectures in Yiddish a few months before. People began complaining and protests broke out.

Zhitlowsky had been invited to give an important lecture to a workers group in Tel Aviv, but the students of Herzliya found Zhitlowsky’s lodging in Jaffa and surrounded it, refusing to let him out to give his lecture until he negotiated with them. “Zionism was a revolutionary movement. And these people were fanatics,” Portnoy remarked.

‘Ivri, daber ivrit!’

Not surprisingly, the Herzliya school was the birthplace of the extremist organization, the Language Defenders Battalion, in 1923.

The Battalion was militant in its efforts to enforce Hebrew no matter what, using propaganda (most famously, ivri, daber ivrit! or “Hebrew, speak Hebrew!”), intimidation and violence. Its members attacked Yiddish theater performances and closed down the offices of Yiddish publications.

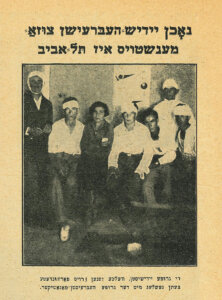

An important photo in the exhibit is one Portnoy found in the Yiddish publication Ilustrirte Vokh showing a group of bandaged people with the caption: “This group of Yiddishists was gravely wounded during a fight with Hebrew fanatics.”

Ya’akov Zerubavel, a Yiddish-supporting Zionist activist, commented on the state of the language in the 1930s: “Worse than the persecution was the methodical, psychological and ideological pogrom practiced by the authorities against the right to use the Yiddish language.”

Upon arrival to pre-state Israel, Ashkenazi immigrants were given a short timespan to drop Yiddish and learn Hebrew. “The Zionists actually made a rule that if you had been in the country for two years, you were not permitted to speak Yiddish in a public meeting; you had to speak Hebrew,” said Portnoy.

Those who soldiered on to write literature in Yiddish received little financial support. On the other hand, unlike their Hebrew-writing contemporaries, they were free to write about what they wanted. They didn’t need to stick to any ideological script.

Yael Chaver, a scholar at Berkeley, specializes in Hebrew and Yiddish literature of pre-state Israel. “I think because they were such a minority and essentially not encouraged and not supported, they had more leeway,” she said.

“Yiddish writers tackled topics that Hebrew writers of the time did not,” Chaver said. There was one story, for example, about a Jewish boy hunting for wild boar to sell to Greek Orthodox priests, stumbling upon a group of people dressed as Arabs but holding a Passover seder. “It’s a whole blurring of dimensions here. And no Hebrew writer of the time addresses anything like that.”

Yiddish in Gaza?

Despite the attempted destruction of Yiddish, the language has lived on in Israel in unexpected ways.

The Hasidic community grew much faster than Zionist leadership ever anticipated, and tens of thousands of them continue to speak Yiddish.

On the secular side, the government began to loosen its grip on Yiddish in the 1950s, but the language was spoken more freely after Russian immigration in the 1980s brought a large number of Yiddish speakers and writers to Israel. Organizations like Leyvik House and YUNG YiDiSH, and a Yiddish radio program produced by the Israel Broadcasting Authority, helped serve the cultural needs of these new immigrants.

Ghil’ad Zuckermann has theorized that Modern Hebrew, being formulated by Yiddish speakers, has Yiddish as part of its DNA. A memorable example: ma nishma or “what’s happening?” (literally, “what’s heard”) isn’t found in any previous incarnation of Hebrew, but is widely used in Yiddish (vos hert zikh?) and other languages.

But the most interesting way Yiddish lived on in the Holy Land was how it continued to be remembered by some Palestinian Arabs. Michael Dorfman wrote about some Gazans, whose parents had spoken Yiddish with the Ashkenazis of the Old Yishuv. They ended up speaking Yiddish to the Israeli soldiers, many of whom still knew the language, when they entered Gaza after the victorious 1967 War.

“The soldiers related this to the compilers of a seminal military history, but I heard that the editor decided not to include this story so as to not violate the myth that Yiddish had been left behind in the Diaspora,” Dorfman said.

“Palestinian Yiddish” is on display for the fall of 2023 at YIVO, located in the Center for Jewish History, on 15 West 16th St., New York City.