Believe it or not, there’s a Yiddish guide to Palestinian Arabic

Its eccentric author also wrote a Hebrew translation of Buddhist teachings

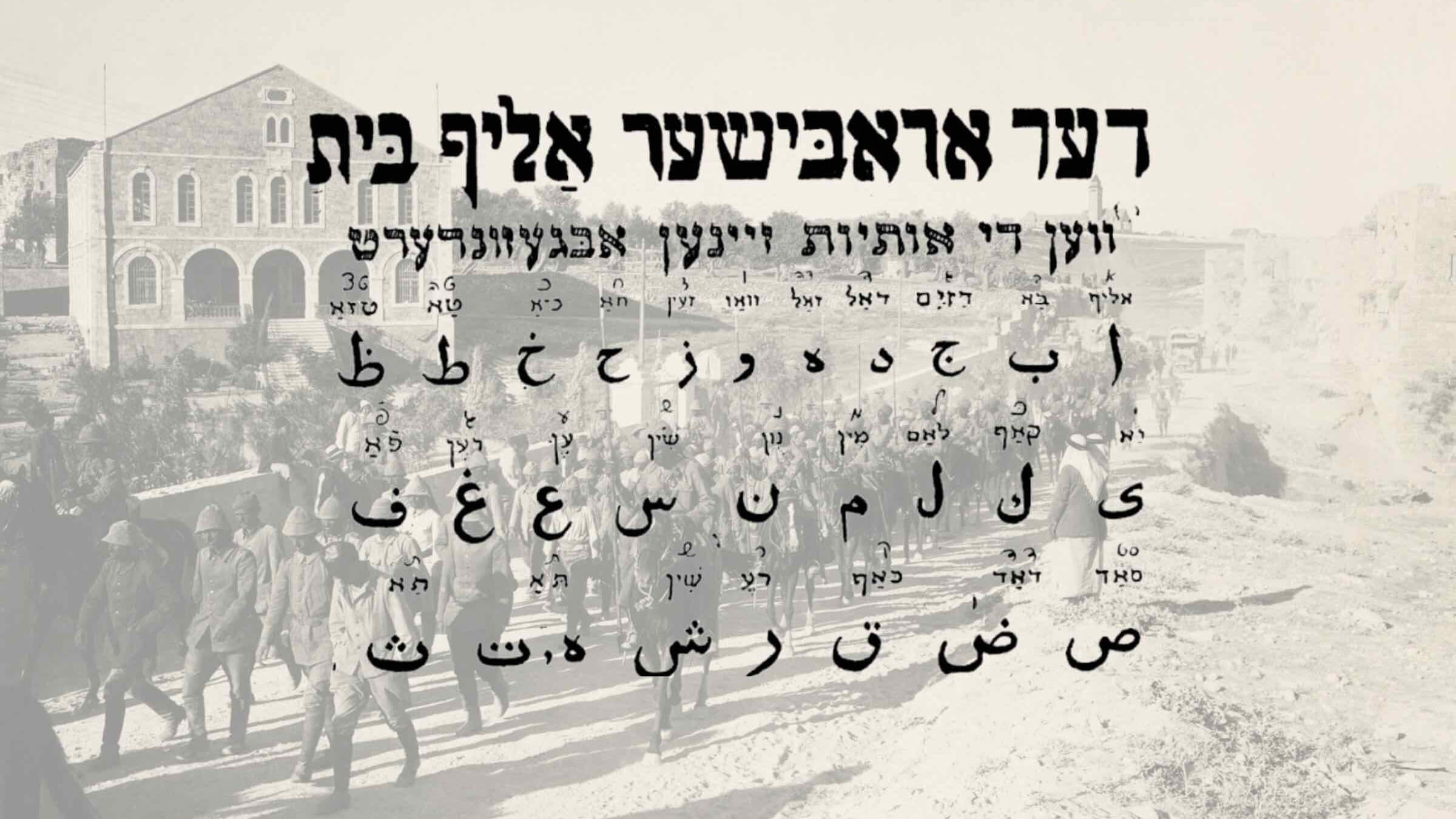

The Arabic alphabet as taught in the “Arabic Yiddish Guide,” with World War I’s Battle of Jericho in 1918 in the background. Graphic by Zach Golden

Read the original article in Yiddish.

Do you know Yiddish and want to learn a little Arabic? Take a look at Getzel Selikovitsch’s 1918 Yiddish booklet called “Arabish-Idish Lehrer” or Arabic Yiddish Guide.

The very same author also wrote a book in Hebrew about Buddhism called “The Teachings of Buddha.”

This year marks the 160th anniversary of Selikovitch’s birthday, although if you look him up in the “Biographical Dictionary of Modern Yiddish Literature,” a footnote suggests that he was born not in 1863, but in 1855.

I found out about this unusual textbook from the writer Olga Fiks, who works as a midwife in Israel, understands Yiddish and is studying Arabic. Among her patients she hears both languages: Yiddish-speaking Haredis and Arabic-speaking Muslims and Christians. She herself has authored a number of fantasy novels and short stories in Russian.

Getzel Selikovitsch was born in the Lithuanian town of Rietavas. His father was a “Poresh,” a follower of the Vilna Gaon, and learned Talmud day and night. In his youth, the future writer quickly took to his Yeshiva studies and chose to become a rabbi, but because of his mother’s influence he received a secular education. In 1897 he went to Paris where he studied ancient Egyptian, Ge’ez and Sanskrit and a number of modern languages including English and Arabic. In 1885 he volunteered as a translator for a British military expedition to Egypt. But then he was accused of being overly sympathetic towards the Africans, so he moved to Paris where he continued his studies at the Sorbonne and became a professional Egyptologist.

In 1887, Selikovitsch settled in the United States and took a position for a short time as a professor of Egyptology at the University of Pennsylvania. He was then forced to leave due to internal politics. Then he decided to become a writer and a journalist, adopting the American name George.

Later he edited a number of Yiddish newspapers. To make some extra money, he wrote pulp fiction in Yiddish with cliched and melodramatic names like “Madam yetzer-hore” (Madame Temptation) and “Di bitere nekeyve” (The Bitter Woman.) But he also deeply appreciated high literature. In the conflict between the sensationalist writer Shomer and Sholem Aleichem, he sided with Yiddish’s literary great. He passed away in 1926.

Selikovitsch’s “Arabic Yiddish Guide” was published in 1918. It’s a small 32-page booklet consisting of 12 lessons. Over the years there were several editions of it. Apparently it was quite popular. Selikovitsch writes that the guide is “for the use of the Jewish Legion in Palestine” — a textbook that could help Zionist colonists in the Land of Israel speak to the local Arabs. The book actually begins with a Zionist poem in solid ancient Hebrew. It looks like Selikovitsch really wanted to express his own fondness for Eastern languages and cultures, and hoped also to make some money off of it.

Selikovitsch’s attitude towards Arabic is actually quite interesting. Most Arabic textbooks teach Classical Arabic, which is significantly different from the various spoken dialects. To top it off, the dialects themselves are very distinct from each other, like Spanish is to French. But traditionally, all forms of Arabic are considered one language. The standard from which Classical Arabic draws from is, naturally, the Quran. But the old Quranic language sounds quite archaic in comparison with Modern Standard Arabic, used in the press and on television today. Because of this it makes more sense to see Arabic as a group of languages and dialects.

Selikovitsch, on the other hand, focuses on the spoken Palestinian dialect of Arabic of the early 20th century. Oddly, he doesn’t introduce the Arabic alphabet until the end of the textbook. His chart displays only separate letters which are never found in normal Arabic text. It’s difficult, and may even be impossible, to learn the alphabet from just one page.

Instead of writing Arabic in the traditional way, Selikovitsch created a unique system that looks like a mix of pseudo-Yiddish spelling and classical Yiddish-Arabic transliteration (as, for example, from some of Maimonides’ sacred books which he wrote initially in Arabic.)

The well-known Hebrew writer Mikhah Yosef Berdyczewski once suggested Selikovitsch translate a collection of stories and thoughts from “Tripitaka” in the Buddhist canon, which, by the way, is written not in Sanskrit but in a similar Indian language called Pali. Selikovitsch actually went through with it. In 1922, he published a Hebrew translation of it called “Sefer Torat Budha” or The Teachings of Buddha. Both works, the Arabic Yiddish Guide and The Teachings of Buddha, are rare examples of “Yiddish Orientalism.”