The filmmaker who challenged his Haredi community’s prejudices

Menachem Daum believed that reaching out to Poles and other non-Jews was part of his holy work in creating a better world

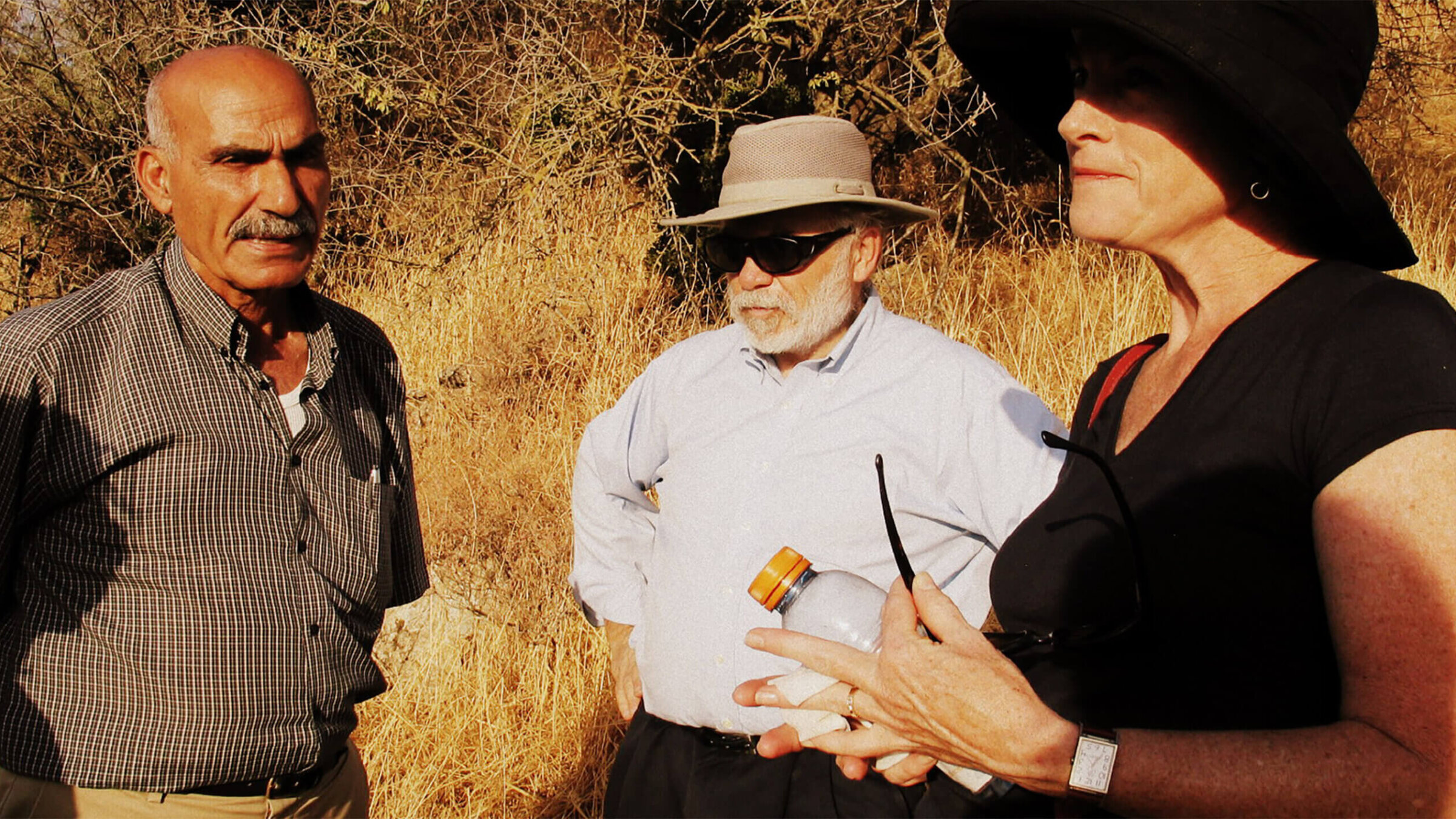

Menachem Daum (center) with Yakoub Oded (left) on the set of The Ruins of Lifta, 2012. Photo by Kamila Klauzińska

Acclaimed filmmaker Menachem Daum, whose documentary films challenged stereotypes that Haredi Jews and non-Jews had of each other, died Jan. 7 of cardiac disease. He was 77.

I met Menachem almost 30 years ago, when he and another filmmaker, Oren Rudavsky, came to Bergen County, New Jersey, while working on a film about Orthodox Jews and the secular world.

They wanted to know if they could ask me questions about how I went off the derekh — leaving the Orthodoxy of my youth. I gave them an earful about having been an agunah, a chained woman whose husband refuses to grant a get (divorce). After the divorce finally went through, I walked away from the community.

Menachem, a son of Holocaust survivors, was a former gerontologist who quit his practice to “make movies.” Oren is the son of a Reform rabbi.

When Menachem switched to filmmaking, he earned a living by filming Jewish weddings and organization benefit dinners. But then he began making films that opened hearts and minds. He jokingly called it holy work. And it was.

The film that Menachem and Oren were working on when I met them, A Life Apart: Hasidism in America, was a first. Narrated by Leonard Nimoy and Sarah Jessica Parker, it covered the American Hasidic community in-depth, examining their traditional lifestyle and the various Hasidic sects in Brooklyn. It also explored how Haredi Jews and non-Jews see each other — an issue which had consumed Menachem since a trip to Poland that he took with the late singer-songwriter Shlomo Carlebach in 1988.

That trip was a game-changer for Menachem. For most of his life he had been living an insular “shtetl life.” But going with Shlomo to those concerts in Poland, whose audiences were almost all non-Jews, he noticed that Shlomo didn’t rebuke them for the “sins” of some of their parents during the Holocaust. Instead, he sang to them with love.

Menachem adopted Shlomo’s approach and made it his life’s mission to spread Shlomo’s message. He worked for years on that film, desperately trying to get funding for it — even just days before he passed away.

“Contrary to most of us, Menachem embraced the concept that all human beings were born in God’s image,” Oren told me by phone. “He believed that he needed to find common ground with those he had been taught were our eternal enemies — including the Polish people that his community said had been complicit with the Nazis. In his films, he challenged his own prejudices and those of his community.”

Menachem often said that nothing infuriated him more than rebbes telling his grandchildren to “hate goyim because they all hate us.”

Born in 1946 in the Landsberg DP camp in Germany, and deeply influenced by his parents’ hellish experiences in the Holocaust, Menachem was driven to preserve memories of the past by linking them to the present. I believe that he suffered from what historian Henry Feingold called “the shpalt,” the split. It’s a form of cognitive dissonance common to many sons and daughters of Holocaust survivors who had one foot firmly planted in pre-Holocaust European Orthodoxy, and the other just as firmly planted in American soil and pop culture.

That shpalt compelled Menachem to ask questions his fellow Haredi Jews avoided — questions about the faith (or lack of faith) among certain survivors and how Jewish values were often distorted by xenophobia.

In his 2004 film Hiding and Seeking, Menachem takes his Haredi sons to Poland to find those who had rescued his father-in-law and his two brothers. The film’s footage of Menachem gently caring for his stroke-stricken father demonstrated the kind of person he was, as did his determination to find his father-in-law’s rescuers and to thank them and praise them for their courage.

“Menachem did what seemed almost impossible,” said Michael Berenbaum, co-producer of the Oscar- and Emmy-award-winning film One Survivor Remembers: The Gerda Weissmann Klein Story, who was one of Menachem’s advisers and a good friend. “He explained Haredim to the gentiles and explained Polish Catholics — his in-laws’ rescuers — to his increasingly insulated children. He was a master filmmaker and a man of decency and integrity seeking truth and humanity in those who would be ‘othered.’”

In 2016, Menachem produced The Ruins of Lifta, about two people with a tragic history. One was an Israeli Arab, Yakoub Oded, whose family lost everything after a massacre by Menachem’s uncle and the Stern Gang. The other was Dasha Rittenberg, an outspoken survivor of the Blechhammer concentration camp, a subcamp of Auschwitz.

Eva Fogelman, author of the book Conscience and Courage about rescuers of Jews during the Shoah, was a close friend of Menachem’s. “We saw each other at events that I attended with Dasha. And as she aged, we coordinated caring for her, because it took a village to care for her.”

Charmed by Dasha’s indomitable spirit, Menachem brought her to Israel to work on the daring film. They went to the ruins of Lifta where he introduced her to Yakub. The two survivors, one of the Holocaust and the other of the Nakba, shared their losses caused by hatred. Whether or not he succeeded in bridging the gap between these two people is something viewers need to determine for themselves.

Menachem was so much more than a filmmaker. He was a devoted husband, father, grandfather and great-grandfather and friend who flew kites with his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He was an avid biker and kayaker. He was kind, generous, and classically stubborn.

He told us often how important it was to bridge gaps between Jews and non-Jews. Those of us — his colleagues, friends and believers in his message, now need to figure out how we can continue his holy work, spreading the messages from his heart and soul to the world.