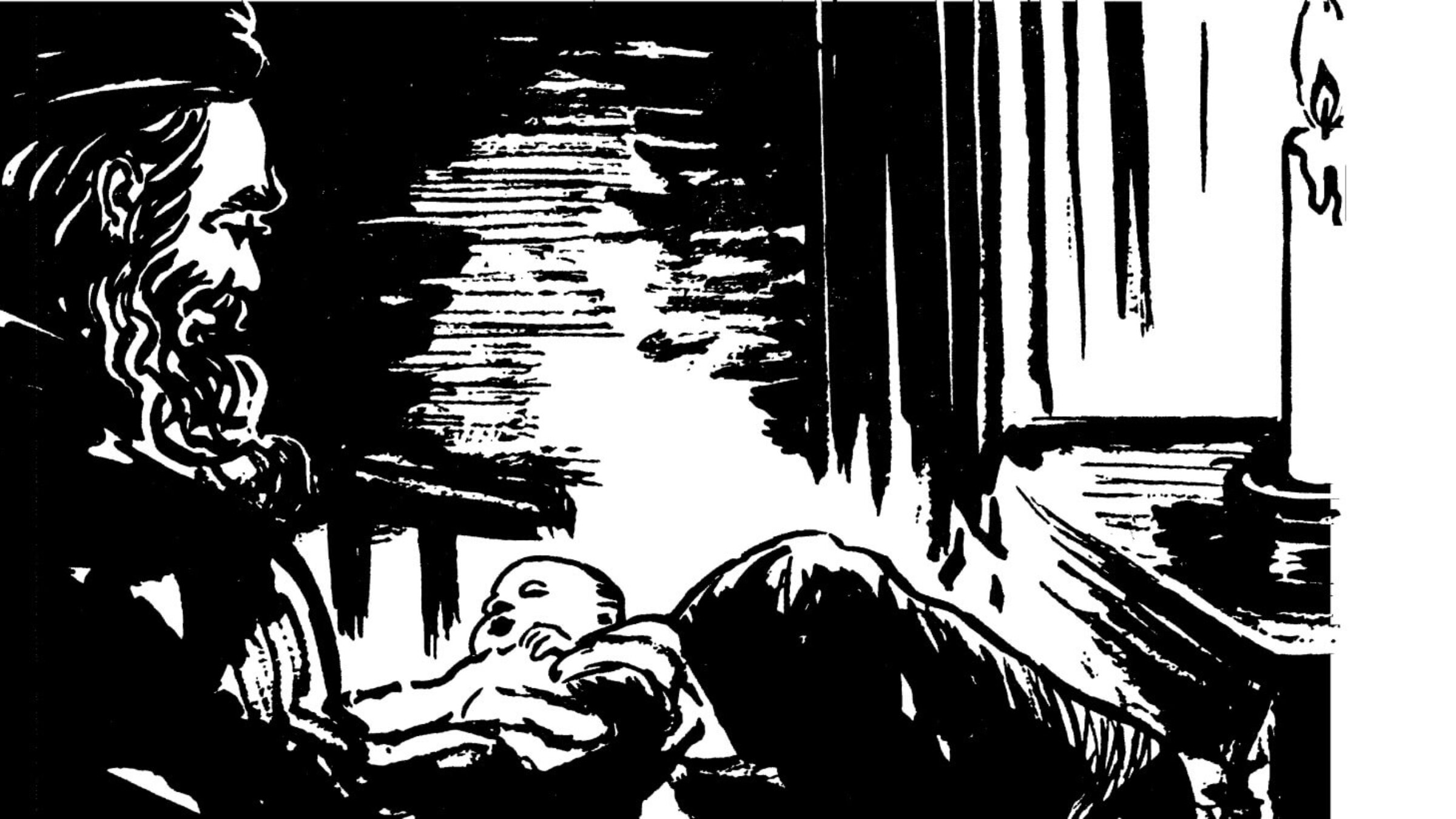

‘The rabbi who was late to Kol Nidre’ (folktale)

The Yom Kippur prayer service is about to begin and all the townspeople are there. But who’s watching the babies?

Courtesy of the Workers Circle

This story, which is translated from the Yiddish, is the second in a series of Yiddish holiday tales for children that will run throughout 5785. Read the original Yiddish text on page 24 of this anthology.

In the twilight moments before the Kol Nidrei service that ushers in Yom Kippur, the Torah scrolls are removed lovingly from the ark, congregants are decked out in angelic white, and a holy hush falls over the entire synagogue.

But who’s watching the community’s babies? Many contemporary parents can relate to the tension between attending this highly anticipated prayer service and caring for children too young to accompany them.

While it used to be assumed that mothers would shoulder the burden, “The Rabbi Who Was Late to Kol Nidre” imagines a scenario where the town’s (male and rather senior) rabbi delays his own attendance in shul to comfort two children left alone at home. As it turns out, he is one of several humane rabbis who populate the pages of modern Yiddish literature, most famously in the neo-Hasidic tales of Y.L. Peretz. These character types express a vision of yiddishkeit that is bound up with mutual care and regard for the most vulnerable among us.

The story, originally an anonymous folktale, is retold by Yiddish educator and children’s author Yudl Mark and printed in Dos lebedike vort (The Living Word), a collection of stories and poems published in New York in 1954 for use in the Yiddish schools run by the fraternal organization Workers Circle.

Mark took pains to minimize the conflict between domestic labor and the dictates of Jewish law. To comfort a crying child is not just an act of kindness, khesed, insists the rabbi in the story, but “a great mitzvah.” Today, liberal denominations tend to translate the term mitzvah as a “good deed,” while more traditional Jews default to “commandment.” What if it were both at once?

A Hasidic teaching understands the word “mitzvah” as deriving not (only) from tsav, the Hebrew root meaning “command,” but also from tsavta, meaning “bond.” This root may be familiar from the Modern Hebrew term for “team” or “crew” (tsevet). The rabbi sees himself and his congregants, who are also his neighbors, as part of the same team, bound by ties of mutual care and responsibility. Far from viewing the delayed Kol Nidrei as a mishap, the rabbi asserts that the Almighty had bashert, or destined, him to perform the great mitzvah of cradling the hungry baby.

While the child’s mother will ultimately miss the service, the rabbi seems to suggest that her tasks at home carry the weight of holiness as well. (The child is referred to in grammatically neutral terms in Yiddish, its gender undisclosed and unimportant; hence the use of “it” in English.) Consoling the infant is also a source of pleasure, bringing a smile to the rabbi’s face, and perhaps a tingle to the chin under his beard, long after the cuddle ends.

The Rabbi Who Was Late to Kol Nidre

I.

The holiest night of the year is the night of Kol Nidre. The big synagogue is full. Jews are standing, their heads covered with their prayer shawls. Old men are wearing their kitlekh, the white robes resembling shrouds. All of them are absorbed in quiet piety. They’re waiting. Nobody says a word. The Kol Nidre prayers are sure to begin any minute now.

So why weren’t they starting? The cantor had been standing at the prayer lectern for a long time. He’d finished reciting the silent prayer that precedes Kol Nidre awhile ago. Who were they waiting for? After all, the time for beginning Kol Nidre was long past.

The old rabbi hadn’t come yet! They couldn’t start without the rabbi, of course. But where could he be? The sexton had already stopped by the rabbi’s house: he wasn’t there. He’d left home some time ago — bound for Kol Nidre. So what on earth could have happened to him?

II.

The rabbi had been walking slowly to Kol Nidre when he passed a poor hovel and heard crying, like that of a child. The rabbi stopped and listened; the crying was coming from inside. Opening the door, he noticed a cradle with a baby in it, and next to the cradle, a little girl of about six.Both children were crying.

“Why are you crying, little girl?” asked the old rabbi.

“Mama went out to Kol Nidre and left me to watch the baby,” the girl sobbed. It woke up suddenly and started crying hard, and I don’t know what to do….”

The rabbi picked up the crying baby and carried him around the shabby room, smiling and talking to the child until it stopped crying. It stuck out a hand toward the rabbi’s gray beard and played with the long hairs. The six-year-old sister had stopped crying too.

“Nu, you see? Everything’s fine!” said the rabbi, laying the baby back down in the cradle. The child burst into tears once again, and the sister began to whimper as well.

The rabbi took the baby back out of the cradle. Once again, he carried it in his arms, singing prayer melodies to the child. The baby calmed down, but as soon as the old rabbi lay the baby back into the cradle, it began to cry anew.

“This baby is probably hungry,” the rabbi said to the little girl.

“It’s possible. Mama couldn’t feed the baby because it fell asleep and she didn’t want to wake it,” the sister said.

“If that’s the case,” replied the old rabbi, “Then go to the synagogue and call your Mama.”

“I would have done that long ago, but I can’t leave the baby alone!” exclaimed the six-year-old sister.

“I’ll wait here, until you come back with your Mama,” the rabbi assured her.

The sister left to fetch their mother. Meanwhile, the rabbi dandled and rocked the baby in his arms, rocked it, humming some more prayer melodies. The hungry baby smiled and played with the hairs of the rabbi’s beard. The infant lay calmly and happily in the arms of the old rabbi, listening intently to his melodies…until Mama came home from synagogue.

III.

With quick steps, the rabbi rushed into shul.

People ran up and asked, “Rabbi, what happened to you? Are you alright? Tell us, what’s the matter?”

“Nothing, nothing,” the old rabbi assured his congregation. “On the way to Kol Nidre, God destined me to do a great mitzvah. I heard a child crying, so I went inside, and held the child. Soothing a crying child is a great mitzvah!” Thus did the rabbi explain, in a quiet and halting voice, why he had come late to Kol Nidre.

“Kol Nidre…” the cantor began to intone. The whole congregation recited the Yom Kippur prayer with quiet devotion. The old rabbi kept smiling, as if he were still holding the baby in his arms.