Revisiting the 1998 murder of an abortion doctor in the wake of Roe news

‘When you have choices, you can be empathetic to a side that wants to take them away.’

An anti-abortion demonstrator blows a shofar outside the U.S. Supreme Court on May 5, 2022 in Washington, DC. Photo by Tom Brenner / Getty Images

This is an adaptation of Looking Forward, a weekly email from our editor-in-chief sent on Friday afternoons. Sign up here to get the Forward’s free newsletters delivered to your inbox. Download and print our free magazine of stories to savor over Shabbat and Sunday.

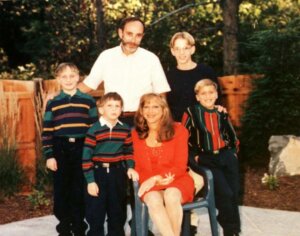

Dr. Barnett Abba Slepian had just returned home from synagogue after saying kaddish on the first anniversary of his father’s death and was heating up a bowl of soup in his kitchen when he was fatally shot by a rabid anti-abortion activist on Oct. 23, 1998. Slepian, an obstetrician-gynecologist known as Bart, was the seventh of 11 people murdered by supposedly pro-life forces in the United States, the most twisted and horrific aspect of the way the abortion debate has cleaved the country and distorted our politics over the last half century. He was 52 years old and left four sons, ages 7, 10, 13 and 15.

I had just started as a reporter at The New York Times when Slepian was killed, and was sent up to Buffalo to help cover the aftermath. One of the stories I did was a profile of the anti-abortion activists who prayed and tried to persuade patients not to proceed with their plans at the Buffalo clinic where Dr. Slepian performed abortions about eight hours each week.

“Punching a clock to fight abortion,” was the headline on the story, which described how the clinic protest was more like a job than a political activity for the 80-some activists involved; there was a schedule and people counted on them to show up. The local stalwarts I met denounced not only Dr. Slepian’s murder but also the violent and aggressive tactics deployed by some of their colleagues, including blocking clinic doors, shouting profanities at patients, threats of any kind.

My new boss, Joyce Purnick, then the Metropolitan Editor of The Times, praised the piece as a paragon of empathetic reporting, saying she had rarely seen such a fair and full portrait of anti-abortionists in a liberal media landscape generally dominated by journalists committed to abortion rights. For nearly a quarter century, I have held onto that article as a hallmark of the independent journalism I believe is crucial to a healthy democracy, journalism that represents people respectfully regardless of ideology or anything else.

Until this week, when Politico published the draft Supreme Court opinion making clear that the landmark Roe v. Wade decision guaranteeing the right to terminate a pregnancy would soon be overturned.

I was 27 when I interviewed those anti-abortion protesters. It was before I’d ever been pregnant, before I exercised the choice provided by Roe to have two abortions, before I gave birth to twins who are now 14. Maybe that made it easier for me to see all the sides. Or maybe it was because we were 25 years into the Roe era, with abortion-rights enshrined in our Constitution and our culture, and so it seemed like a simple matter of letting a minority view be aired.

“When you have choices, you can be empathetic to a side that wants to take them away,” said Amanda Robb, Dr. Slepian’s niece and a fellow journalist who has spent much of the last two decades covering the abortion wars. “When you don’t have choices, it’s very hard to be.”

I reached out to Robb, who saw Dr. Slepian as a kind of surrogate father after her own died when she was 4, as I revisited the Buffalo story in the wake of the Roe news. She had written a searing piece for New York Magazine in 2003 in which she said her uncle “didn’t like doing the procedure” and that his reasons for performing abortions “pissed me off.”

“A woman’s right to choose never made the top five,” Robb explained in the article. Instead, Slepian did abortions to pay off student loans, to prevent unwanted children from being born, to ensure the few other willing doctors in the area would not be overwhelmed, to stand up to bullies. After she gave birth herself, and witnessed several abortions, Robb wrote, “I had to admit Bart had a point about abortion being the ‘killing of potential life.’”

In the aftermath, Robb became obsessed with James A. Kopp, the man now serving a life sentence for killing Dr. Slepian. She has just finished a seven-part series for the podcast “Someone Knows Something” investigating Kopp’s involvement with four other abortion-related shootings; it airs on Apple TV+ starting May 11 and everywhere May 25.

When the Roe draft was leaked this week, Robb said, she started “working hard to get Canadian citizenship” (her grandmother was Canadian). “I don’t think this is a safe place for my daughter,” who is now 22, she explained. “When you force people to have babies, you’re in Taliban territory.”

I also spoke this week to Rosina Lotempio, the main anti-abortion protester profiled in my 1998 article. She was then a 58-year-old mother of three and grandmother of six, wearing black earmuffs and a white turtleneck with a silver pin of baby feet as she clutched brown rosary beads, praying quietly to stop abortion.

Now 81, Lotempio told me she moved from Buffalo to Fort Lauderdale after her husband died, remains staunchly convinced that abortion is murder and still donates to the pro-life movement, but no longer regularly attends protests. “I’m more mellow now,” she explained. “My views are still the same.”

Not so the Rev. Robert Schenck, who in 1998 was a Buffalo-based anti-abortion leader who made headlines when he laid a bouquet of seven roses at a memorial for Dr. Slepian — only to have Slepian’s widow, Lynne, send the flowers back with what he described as “a severe note.” Schenck, an evangelical Christian who devoted decades to fighting against abortion rights, has had a conversion in recent years.

When we spoke yesterday, he told me the roots of his transformation go back to Dr. Slepian’s killing, because of what he now sees as his “disastrous decision” to bring those roses to the memorial, and because of a photo showing Kopp at one of Schenck’s own news conferences. “I was sure he was an invader, he didn’t share our principles,” Schenck explained, “and seeing that photo, I realized, ‘Oh no, he’s one of us, he’s in our movement.'”

Still, Schenck stayed in the fight against abortion for years, with a headquarters across from the Supreme Court — he said he met several times with Justice Samuel Alito, the author of the draft opinion overturning Roe, and recognized language in the opinion from those conversations. But Schenck eventually came to see the movement as hypocritical, and called the forthcoming Supreme Court “a Pyrrhic victory.”

“The true test of the pro-life movement will be whether in a post-Roe era the same hundreds of millions of dollars that were used to defeat Roe and the massive deployment of human power will now be shifted to a social agenda that will take care of women in crisis and the children they will be forced to bear,” he said. “The answer to that question is no, they will not. We have to stop forcing people to live in our fantasy and start living with them in their reality.”

Schenck told me that he was actually born and raised Jewish, but encouraged to “shop religion and if you find one you like, embrace it,” which he did, at 16. He remains a Christian, and now works to train “ethically courageous leaders” through the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Institute, which is named for, as he put it, “one of the first German leaders to speak out against Adolf Hitler.”

I asked Schenck if he no longer sees abortion as murder. “That’s right, I do not,” he said. “I like to say all ministers harbor doubts, but we’re not allowed to air them about a lot of things.”

I wish I could say my conversations with Schenck, Lotempio and, especially, Robb, had given me some brilliant new insight about what the draft Roe ruling portends for our hopelessly divided democracy. Like Robb, I am deeply concerned about my children coming of sexual age in a post-Roe world. I am also worried about a Supreme Court that throws the most difficult questions back to our broken political system; it is supposed to be a bulwark against those broken politics.

I want to remain committed to the respectful airing of all perspectives. But I cannot fathom turning the clock back to that dark era when only the privileged could choose when, whether and how to have a baby.

My friend and colleague Adam Liptak, who covers the Supreme Court for The Times, made a crucial point in an episode of “The Daily’ podcast this week. While the court has previously reversed its own precedent in landmark cases, including ending segregation and allowing same-sex marriage, he noted, it has always done so in the direction of expanding liberty, not restricting it.

It is clear that overturning Roe does not fit that pattern. And, as Robb put it, it is hard to be empathetic in a world without choice.

Your Weekend Reads

This week’s edition is all about the Supreme Court news. We’ve got an explainer of what Jewish law says about abortion and three opinion essays: arguing that overturning Roe would violate Jews’ religious liberty; that the ruling is a frightening win for “religious fervor;” and that Jewish women on the front lines of the abortion-rights fight should not give up hope. We’ve also included my personal abortion story, published last fall, and a 2018 article in which several Orthodox women spoke about theirs.

Download the printable PDF here.