Artist Nidaa Badwan escaped repression in Gaza. Now she’s taking on Iran.

‘Every part of my body wants to talk about this story,’ Badwan said

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

The sculpture looks at once regal and raw. Its layers of gold forming a female torso could evoke a gown worn at the Met Gala. But one of the breasts is sullied, and below the waist the crinkly, shiny gold leaf gives way to a chalky gray mess, and then a chunk is missing.

“I’m doing this project for the soul of that poor young lady who was killed in Iran,” explained the artist, Nidaa Badwan.

She was referring to Mahsa Amini, the 22-year-old whose September death following her arrest over the contours of her hijab sparked months of protests across the Islamic Republic and, just this week, Iran’s ouster from the U.N. Commission on the Status of Women.

It’s personal for Badwan, who was also harassed by a repressive regime — in Gaza, where she lived until she was 27 — for daring to wear denim overalls in public, for hanging paintings on a bombed-out wall, for teaching kids to make art. But after a remarkable protest of her own, in which Badwan spent months secluded in her small bedroom making irreverent self-portraits, she escaped, overstaying a rare tourist visa to make a new life in Italy.

‘She has been killed, while I was saved’

“Every part of my body wants to talk about this story, not just one piece but all the pieces,” Badwan told me when we spoke by Zoom this week, speaking in Italian with the help of a translator. “When I heard this story, I felt like it was happening again on me. She has been killed, while I was saved and I’m doing art right now.”

I met Badwan, who is now 35, seven years ago, in 2015, when I was Jerusalem bureau chief of The New York Times. Our local reporter in Gaza, Majd Al-Waheidi, heard that Badwan’s alone-in-her-room portrait project, called “100 Days of Solitude,” was going on display in an East Jerusalem gallery, and we were both intrigued.

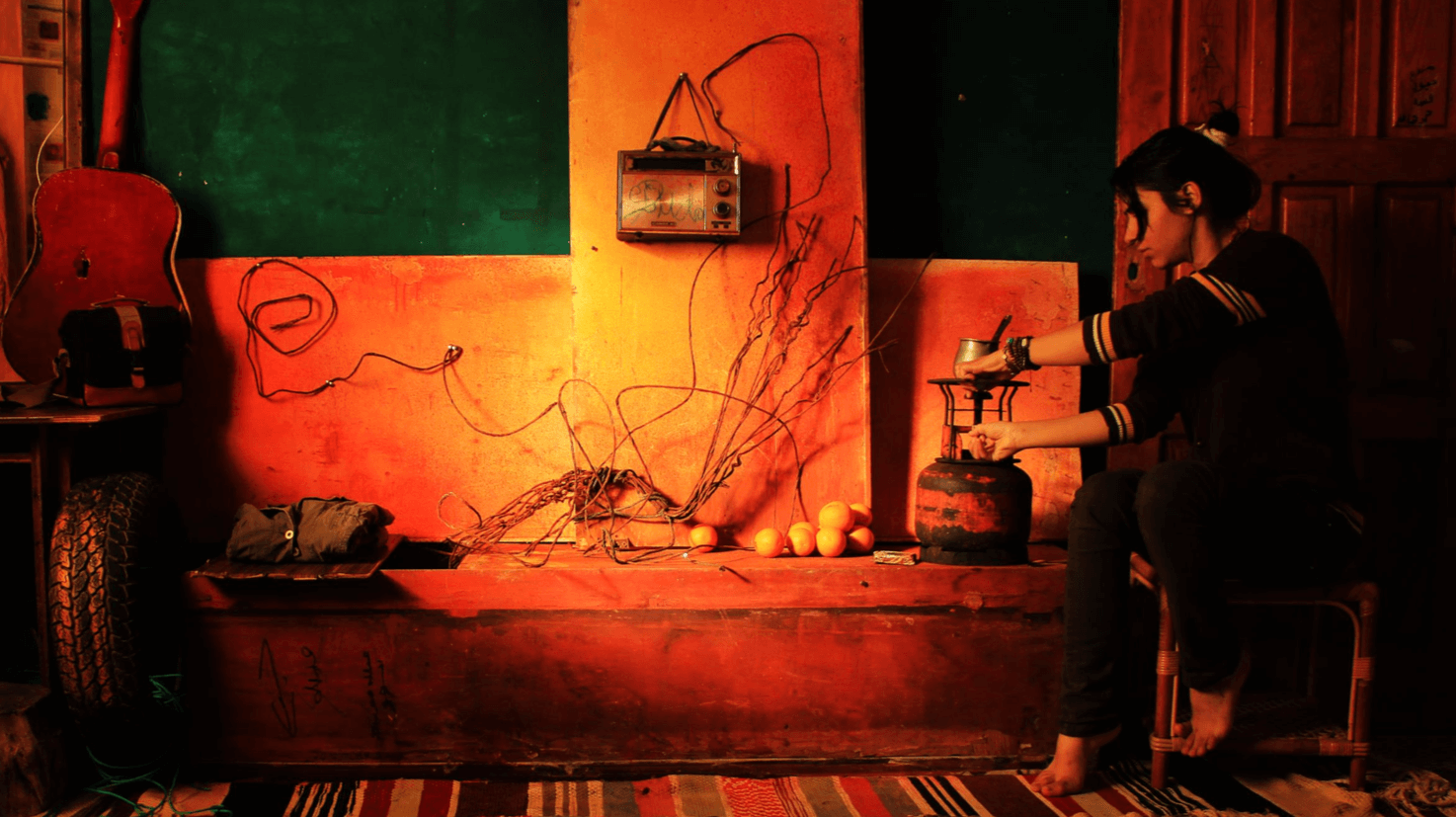

So we went to Deir-al-Balah, the coastal city in central Gaza where Badwan lived with her parents and brother, and spent a couple of hours in that room of less than 100 square feet, “lit by a single window and a bare bulb,” as I described it in my profile. It was small but, like Badwan, brimming with playful creativity— one wall was a patchwork of colored egg cartons; there was a large yellow ladder, a tire swing, an antique sewing machine, two easels, piles of yarn, a gas canister on which she boiled water to make a sweet cappuccino drink from a packet.

A new life in Italy, and new art

My article was widely quoted and translated, and Badwan received many invitations to travel and speak and exhibit her work, including one from Italy’s University of San Marino, to join a show in September, 2015. She obtained a permit to leave Gaza for 10 days, packed a single suitcase, and “didn’t say goodbye to my family,” Badwan recalled.

Those 10 days “were very frenzied,” she said. The university invited her to stay and teach. She met with the local minister of culture. And she met a composer named Francesco Mazzarini who became her manager — and her husband.

“Getting out of Gaza was traumatic, it was a sort of shocking situation,” Badwan said. “I changed my life and I knew I couldn’t go back.”

It was Mazzarini who emailed me, a few months ago, asking for permission to reprint what he called “certainly the main article that opened the story of Nidaa” for this anthology they were putting together, in Italian, chronicling her work and life. It made me curious to reconnect — I knew Badwan was in Italy, and she had occasionally popped up in my social media feeds, but we had not spoken in seven years. Her neighbor, an English teacher, translated for us, and Mazzarini stood behind Badwan in their home in Carpegna, a small town in a tourist area in Italy’s north.

‘I am from the whole world’

Badwan’s face was fuller than when we’d first met; I don’t remember seeing her smile or laugh like this in Gaza. Her Italian was fluid, and she said she rarely interacts with other Palestinians or Arabs, though she showed me a photo of herself with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, and a Palestinian flag, taken in Rome in 2018.

“I don’t feel Italian or from Gaza, not eastern nor western, I am from the whole world,” Badwan said. “I find it very easy to get into and feel well in different cultures and countries.”

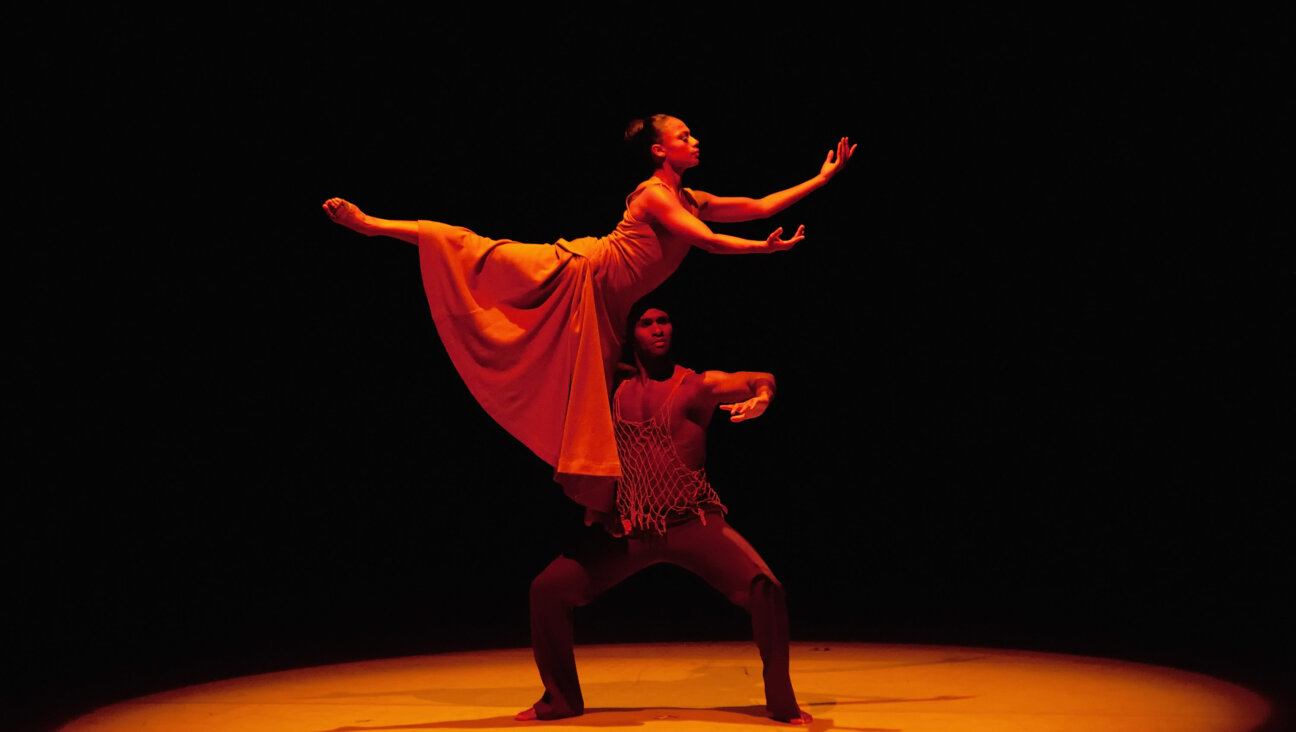

At first, she tried to replicate her Gaza bedroom — “in a figurative sense” — in her studio in Italy, painting the walls the same colors, using the same measurements, but as she has “overcome the bad situation,” Badwan said, “also the walls have changed in color.” She studied the Italian theatrical tradition of leather mask-making, which resulted in a series called “The Game” that riffs on Dante’s Divine Comedy and Commedia dell’Arte. She is working now on a short film, “Rebirth,” in which she will explore “Mother Earth” and “my own roots” by aiming “to free myself from seven uteruses of the past.”

When I’d interviewed her back in 2015, Badwan had said, “I’m ready to die in this room unless I find a better place.” When we spoke this week, I read her back that quote, and said it seemed that she had, indeed, found her better place.

“It’s not easy what I’ve been through,” she said. “I suffered from depression, not only in Gaza but when I first arrived here in Italy. I wanted to work on myself a lot.”

“Going out from my room is a huge responsibility, it’s a weight,” she said, referring to those 100 square feet in Deir-al-Balah. “Freedom is a responsibility. It’s a huge responsibility, what I do, my art is a huge responsibility, because people are watching my art, the symbols, the messages I put inside it. Art is a therapy. And so I take it very seriously.”

‘Every single cell of my own body wants to talk’

Badwan started thinking about the project on the Iranian women’s protests shortly after Amini’s Sept. 16 death. An Instagram video shows how she used her own body to make the mold for the gold-covered torso, which is mounted on a canvas.

“Gold gives a sort of energetic protection — to see a naked body that is still at the same time protected, that’s one of the things I thought while I was doing it,” Badwan explained. The broken part at the bottom, she added, is meant to suggest “that the body is melting.”

“The specific place where the liver stays in the human body, I want to make it like it was eaten,” she continued, “just like it is said when anger gets in the body, the liver gets eaten.” It’s meant to be part of a series — there will be another canvas where “the part of the body grows again, it’s a new birth,” Badwan said. “There are going to be many body parts. Every single cell of my own body wants to talk.”

The work, she cautioned, is unfinished. Like the protests in Iran, like Badwan’s journey as an artist and as a person. Like all of us.