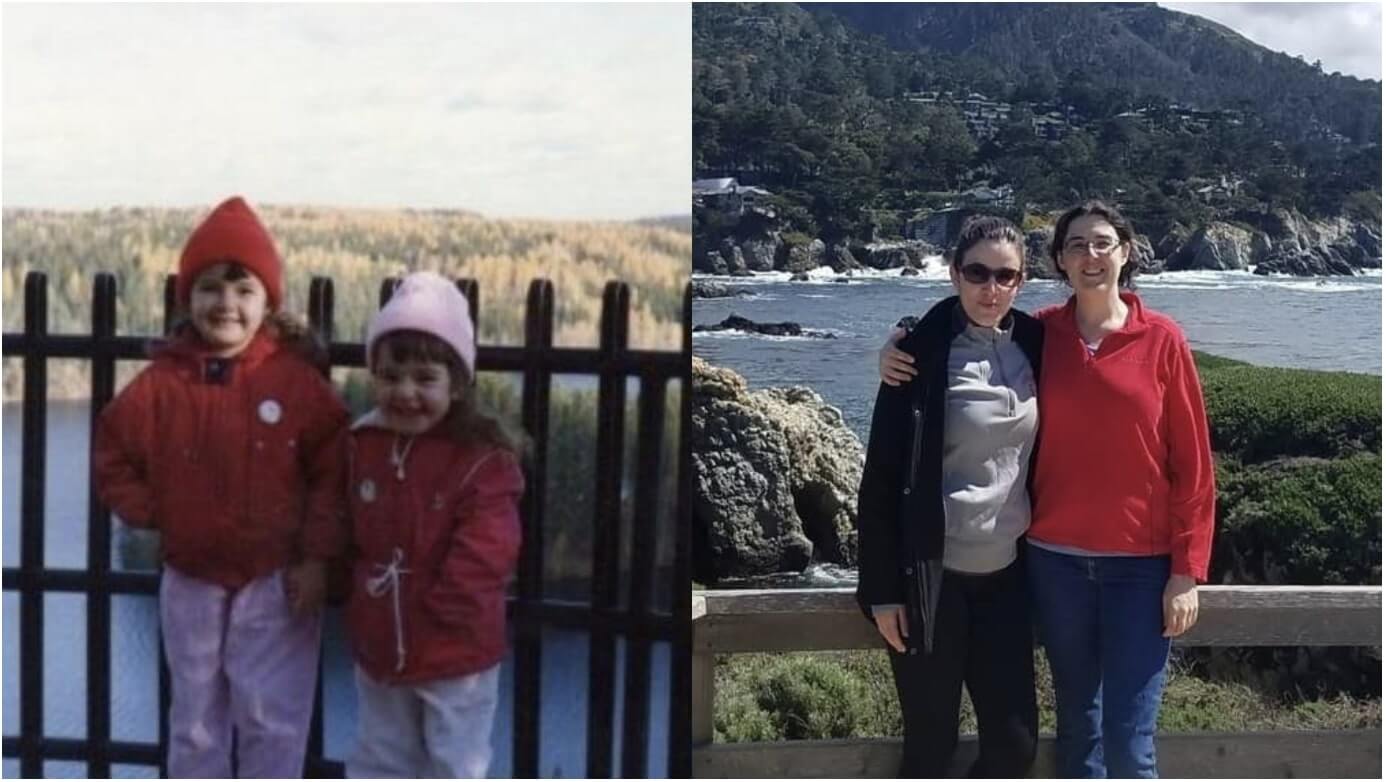

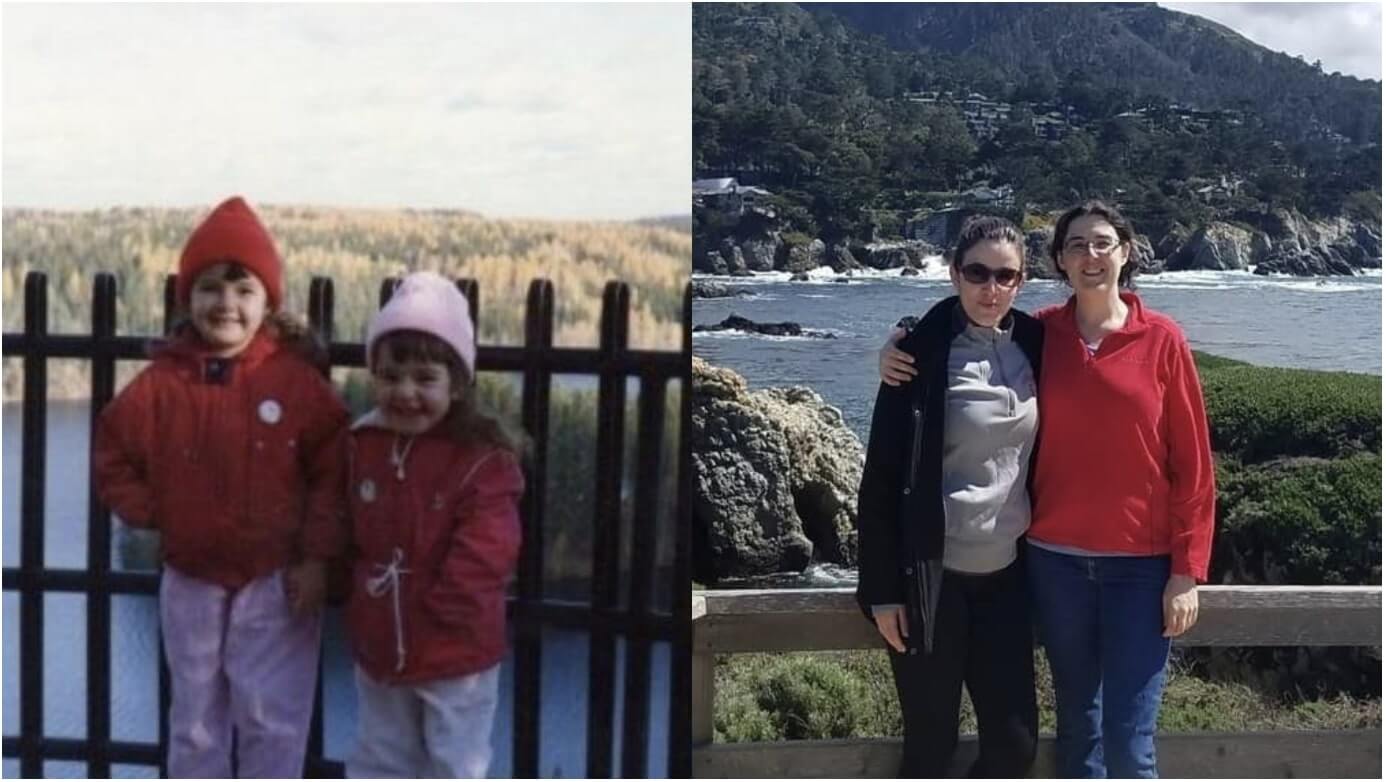

Elizabeth is the oldest of four kids born to Arkada and Ira Tsurkov, Soviet dissidents who spent a year in prison with Natan Sharansky. The family escaped St. Petersburg when Elizabeth was 4 and Emma 3. They shared a bedroom until they were 16 and 15.

“We did everything together,” Emma said. “We played together — we used to have our silly games,” like building imaginary complexes outside that they called “dirt camp,” and read a ton of books. “We pretended like we are what’s left of civilization and we’re building a new camp,” she added, “and we would imagine rules for what’s left of civilization, we would invent new rules.”

Hearing Emma talk about Elizabeth made my heart hurt. I am the youngest of three sisters. We had our own silly games growing up, and have an active text chain that mixes updates about our mother’s health with word-game results, cooking tips and work woes. What if this were happening to us?

I asked Emma what it’s like in the quiet moments between the interviews and the emails and the research, where her mind goes — does she think about what Elizabeth is enduring day to day wherever she is, or is she replaying a slideshow of images of their time together?

“Both,” she said. “I sometimes remember small, stupid, stupid moments.”

Like that time they went shopping at Costco, and Elizabeth plopped down on a sectional sofa and tried out the recliner feature.

“I was like, ‘Listen, your legs are like, all out in the aisle, there are people here,’ and she’s like, ‘But it’s so comfy,’” Emma recalled. “Which is so her. The silly faces she makes. She’s like, ‘Oh, I’m a princess now, I’m sitting on this comfy chair in the middle of Costco.’

“So I remember those silly small moments, but also the bigger picture,” she continued. “She is my sister, I love her and I miss her, dearly, but to other people, all they know is that they would rather she not be their problem.”

On her trip east a couple of weeks ago, Emma met with a desk director — “below the level of deputy assistant secretary” — at the State Department, who said, basically, “that I should let the Iraqis work on it,” which she — and I — found “wholly unsatisfactory.”

“If I just sit around and wait for the Iraqis to get my sister back out of their own free will and good heart, I will never see her again,” Emma said. “She will die at their hands.”

She also sat with aides to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and spoke to her own congressman, Rep. Eric Swalwell, a Democrat elected last year who has written letters on Elizabeth’s behalf to the Iraqi government and to Secretary of State Anthony Blinken.

“That’s the point at which it clicked for me,” Emma said. “How I get my sister back is anyone who cares about my sister pressures Congress and the State Department to apply pressure on the Iraqi government, which then realizes that the political calculus is one that makes keeping my sister kidnapped in Iraq untenable for them.”

Emma also traveled to Princeton, where she met with the provost, Jennifer Rexford. “I was very happy to hear the provost repeat to my face, very clearly, that my sister was in Baghdad doing research for her dissertation that was approved by Princeton — she said so unequivocally,” Emma said.

The university has still not said so publicly, despite “months of back and forth” in which Emma said she “kept getting pushback” and “being distracted by a bunch of irrelevant bureaucratic matters within Princeton — which as I told Princeton, I don’t feel are my concern.”

“My concern is that my sister has been kidnapped and is being held by a terrorist organization,” Emma said in the calm, steadfast tone she held for our hourlong conversation. “She will die there unless we get her out of there. I trust her to keep herself alive there, because anyone who knows her loves her. But I know she is trusting me to get her out of there.”

Just like they could always count on each other to scrub the sticky pan.