Don’t let your kids read this column (but don’t ban it either)

“This is a criticism that I very much enjoy,” said comedian and author Moshe Kasher upon hearing his memoir was banned in a Texas school district.

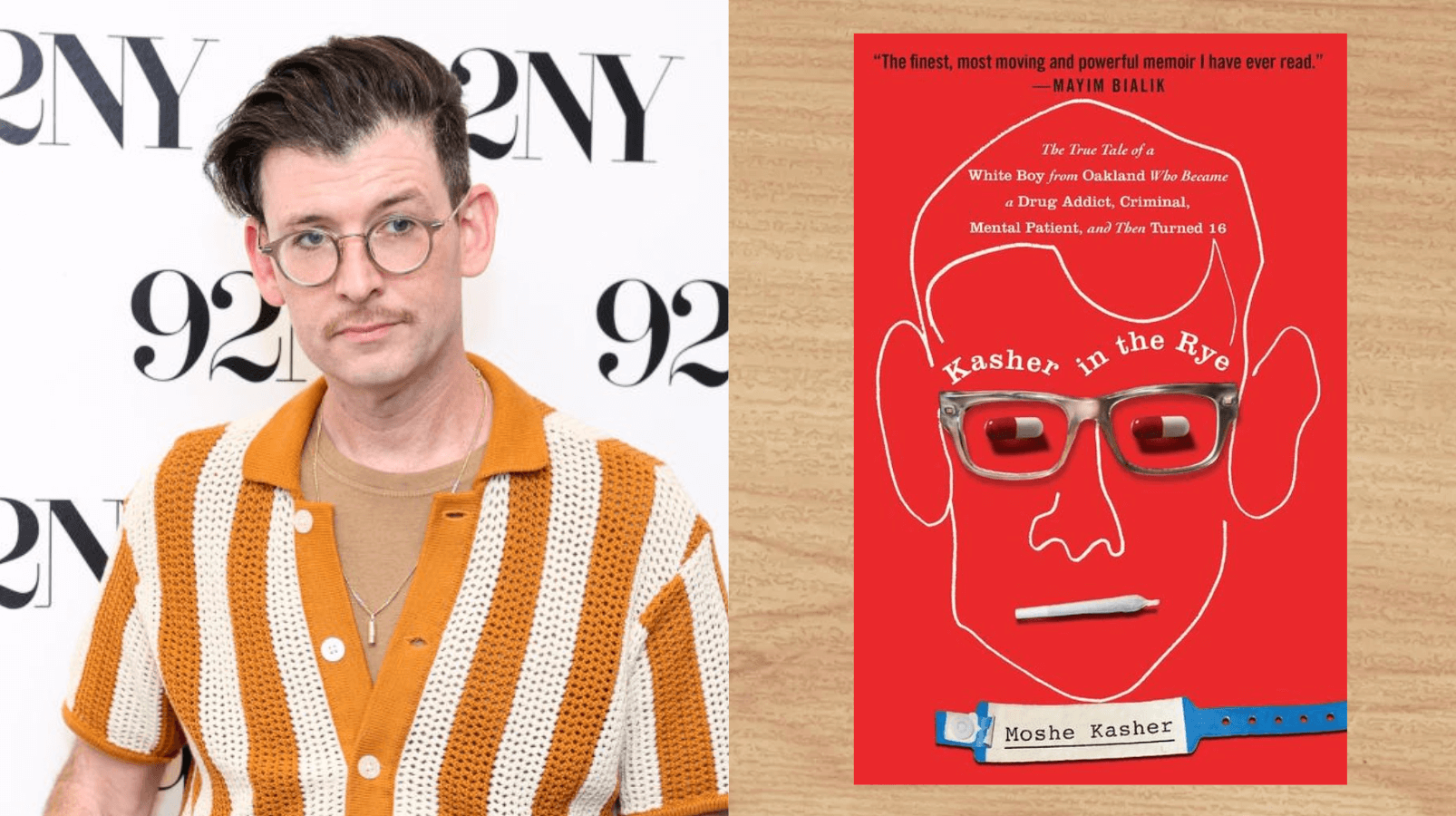

Kasher’s second memoir, ‘Subculture Vulture,’ was published in January. Graphic by Odeya Rosenband. Photo by Arturo Holmes/Getty Images

This column is part of the editor-in-chief’s weekly newsletter, Looking Forward. Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox each Friday.

When I informed the comedian Moshe Kasher that his memoir had been banned by a school district in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, he reacted as though he’d won the Pulitzer Prize.

“I could not possibly be more proud,” Kasher told me. Also “stoked,” “thrilled,” and some unprintable amplifiers.

“I’m normally very sensitive, and any criticism of my work really cuts to the quick,” he added. “But this — this is a criticism that I very much enjoy.”

To be banned is to be in what Kasher called “unbelievable company.” Art Spiegelman and Anne Frank, of course, whose books were also recently outlawed by the former superintendent of schools in Mission, Texas. Kasher, 45, also mentioned J.D. Salinger, whose seminal work inspired the title for his banned memoir, Kasher in the Rye; the poet Maya Angelou; and the hip-hop group 2 Live Crew, whose controversial, explicit albums he grew up on in Oakland, California. “All the great artists,” was how he put it.

“Look, I’m not a prude — I like dirty stuff and vulgarity, obviously, if you’ve read any of my books,” Kasher added. “For me, the litmus test is like: Is it worth it? This kinds of fear-based, reactionary, Dark Ages thinking takes away works that are actually extremely important for kids to read.”

We should stipulate, perhaps, that neither I nor the author think Kasher in the Rye, which was published in 2012, is appropriate reading material for middle school.

It is a racy and very much R-rated story of drug addiction, sexual exploration, mental illness, juvenile delinquency and domestic abuse that is laced with racial and other hateful slurs (plus 361 F-words in its 283 pages, according to the book banners, who apparently counted). One review — in a Texas publication — bluntly advised: “Don’t let your kids read this book.”

“It is a memoir that accounts for the idea that no matter how far down the scales you go, there is always hope and there is always redemption,” said Kasher, whose parents are deaf and who spent his summers in a Satmar Hasidic community in Sea Gate, Brooklyn. “But it is a ribald and vulgar and challenging and racially f—-ed up memoir. I lived in a challenging, vulgar, racially and sexually f—-ed up time. There was violence, there was crime, there was all of these things.

“My kid is going to have to be a certain age before I allow her to crack that book open,” Kasher said of his 6-year-old daughter. “Hopefully, she’ll never crack it open.”

But not really wanting your own kid to read something is very different from a school district prohibiting it. Especially when it is just one of a staggering 676 titles exiled from library shelves by anonymous conservatives who deemed them “filthy and evil.”

Evil? We’re talking about a list that includes Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer, a historic novel about an antisemitic blood libel; The Bluest Eye and Beloved by Toni Morrison; several works by one of my teenagers’ favorite authors, John Green; a book called simply America, by a social worker named E.R. Frank who won a Teen People award; and, one hopes ironically, Kim Hyung Sook’s Banned Book Club.

All book bannings are bad — and, historically, particularly bad for Jews. But what’s most troubling about this one is the broad-brush with which it was adopted.

The Mission school board apparently spent less than five minutes on the matter before banishing all the titles on a list compiled by an outfit called BookLooks, whose rating system mimics one from Moms for Liberty, the right-wing radicals that last year had to apologize after quoting Hitler (admiringly) in their newsletter.

A USA Today investigation published in October found that at least 1,900 of the 3,000 challenges to library books in the prior school year seemed to have been powered by BookLooks.

PEN America has charted a shocking rise in book bans over the past few years, counting 4,349 titles axed around the country just last fall. The Texas Freedom to Read Project launched in December to fight back against bans being proposed all over the state. A parent in the Mission school district has started a Change.Org petition to reverse the ban.

BookLooks, which launched in 2022, rates titles from zero (For Everyone) to 5 (Aberrant Content). The stunning overreach in Texas is obvious as soon as you see that many of the 676 banned books — including Maus 1, Maus 2, and Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation — were rated 2s.

A 2 means “Some content may not be appropriate for children under 13,” according to BookLooks, which raises the question of whether the Texas school board is aware they serve kids older than that.

Kasher in the Rye got a 3: “Under 18 requires guidance from parent or guardian,” according to BookLooks. “I was upset most at the fact that I only got a three,” Kasher said. “The chart’s out of five. But I was shocked that they would ban a three.”

Unlike the Mission school board, BookLooks’ approach is thorough. It offers a handy, alphabetized list of links to excerpts of what it deems offensive material in each work. The one of Kasher runs 20 pages and concludes with a little box showing the number of appearances of profane or derogatory terms (Ass: 82, Bitch: 44, Piss: 41, Tit: 1, plus a bunch I generally prefer not to publish in the Forward.)

I read the BookLooks’ 20 pages on Kasher before I read the book itself. It reminded me of teenagers secretly sharing brown-paper-covered copies of Judy Blume’s Wifey will all the sexy parts underlined in the 1980s. In other words, exactly how not to read a book.

“We’ve gotten to a place in society where context and ideas are less important than orthodoxy,” Kasher said when we spoke.

“Moms for Liberty will never be able to shield their children from scary or objectionable ideas,” he added. “The only thing that happens when you ban a book is you take the thoughtful negotiation with some of these ideas that scare you out of the hands of children, and you allow them only to be exposed to these ideas in the form of TikTok or the internet. And as we all know, there’s no publisher or editor who’s mediating these ideas online.”

The other big problem with book bans, Kasher noted, is that they don’t work. “When I was young and 2 Live Crew’s album, As Nasty As They Wanna Be, got banned nationwide, that was when I went to buy it,” he recalled.

“You cannot keep an idea from a curious mind,” Kasher continued. “It’s doomed and it’s just stupid. It’s just for you. It’s a performance, for you and your constituents.”

The superintendent who pushed for the ban in Mission has been removed from her post over a contract dispute, and my emails to school board members there last week have gone unanswered. As did my request to talk to the head of the town’s public library.

Unsurprisingly, Mission’s library does not have any books by Moshe Kasher, according to its online database, though you can check out Robert J. Kasher’s Passport’s Guide to Ethnic Toronto. There are two copies of The Diary of Anne Frank, plus a couple of Spanish versions; Maus in English and Spanish, plus something called Little Elephant and Big Mouse, which was published in 1981, has 29 pages, and is said to help readers “understand the size difference between the sun and the Earth.”

(The library also does not have Malamud’s The Fixer, but it does have The Fixer Upper, a 2009 novel by Mary Kay Andrews that is described as “a sassy, sexy, sometimes poignant look at small-town Southern life.” The Fixer Upper is not on BookLooks. Or perhaps I should say: Not yet.)

Kasher, meanwhile, this January published a second memoir, Subculture Vulture, which The New York Times called “part history lesson, part stand-up set and, often, part love letter.”

It chronicles his journeys through six distinct worlds — Hasidic Judaism, Deaf interpreters, stand-up comedy, Alcoholics Anonymous and drug-rehab, Burning Man, rave DJs. “May this one be banned as well,” joked Kasher, who during the pandemic hosted a podcast, Kasher vs. Kasher, with his older brother, David, who is a rabbi..

Subculture Vulture is also not (yet?) on BookLooks, though its launch event, hosted by PEN America, was disrupted by anti-Israel protesters targeting his conversation partner and friend, Mayim Bialik.

“It was surreal, it was bizarre, it was upsetting, but it also really felt like it wasn’t about me,” Kasher said of that event. “My primary thought was: With all the anguish and bloodshed that is happening in that part of the world, having an awkward moment at a book event is kind of a small price for me to pay.”

I asked Kasher — who attributes his own teenage turnaround in large part to a school principal giving him Salinger’s Catcher — what books he was reading to his 6-year-old.

He said he’d love to be plowing through chapter books like the Narnia series, but that at bedtime, she mostly wants picture books. Her favorites include the classic Where the Wild Things Are and the very Jewish Kishka for Koppel.

They recently finished Judy Blume’s five “Fudge” books. Which, I am very glad to report, are not on BookLooks.org.