Mahmoud Khalil, Elon Musk and the upside-down world of Purim 2025

Pour yourself a whiskey and consider the things the world’s richest man and the campus protester facing deportation have in common

This is an adaptation of our editor-in-chief’s weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it delivered to your inbox on Friday afternoons.

It’s Purim 2025, the holiday where we must get so drunk that we can’t tell the difference between Mahmoud Khalil and Elon Musk.

Maybe we don’t even need to be drunk. Both men grew up abroad: Khalil in Syria, to a Palestinian family that fled a village near Tiberias in 1948; Musk in apartheid South Africa, where he attended a Jewish kindergarten and graduated from Pretoria Boys High School.

Both first came to the U.S. to attend elite universities: Khalil, on a student visa in 2022, bound for Columbia’s prestigious School of International and Public Affairs, where he received a master’s degree a few months ago; Musk, on something called an exchange visitor visa (J-1) in 1992, to go to the University of Pennsylvania, where five years later he picked up twin bachelor’s degrees in economics and physics.

And both stayed: Khalil, who is 30, married a U.S. citizen in 2023 and got a green card in 2024, making him a legal permanent resident. Musk, 53, was naturalized as a citizen in 2002, and has acknowledged there was “a gray area” regarding his immigration status while working in Silicon Valley before that. (The two women he has married — and divorced — are, respectively, Canadian and British.)

Now Khalil, who led anti-Israel protests at Columbia, is in a Louisiana immigration detention center, facing deportation because the Trump administration has determined that his “presence or activities” would “have serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.” Meanwhile Musk, the world’s richest man and President Donald Trump’s unelected right hand, has dismantled USAID, outraging scores of longstanding American allies and threatening global health.

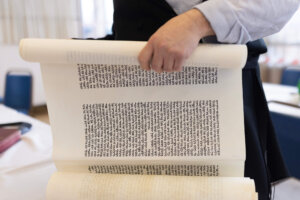

Go ahead, pour yourself a shot of whiskey. It’s Purim, a holiday known for the Hebrew expression nahafochu — to be turned on its head — because it’s based on a story of Jews reversing a decree of death against them. And it’s 2025, when so much of the world really does feel upside-down.

Raise a glass to complexity

The actual drunk-on-Purim thing is, of course, about Haman and Mordechai. Haman is the villain of the Purim story, the aide-de-camp who convinces the king to issue the death decree. Mordechai is the hero, the Jewish uncle who convinces Queen Esther to make the king reverse it. The Talmudic sage known as Rabba said it is our duty “to make oneself fragrant” with wine until we cannot distinguish between the cursed Haman and the blessed Mordechai.

Before you start dashing off your angry letters, let me be clear that this column is not meant to suggest that Khalil or Musk are heroes — or villains. Instead, the point is that the world generally does not divide neatly into good and evil.

I do not support Khalil’s call for Columbia to divest from Israel, nor his defense of student protesters who disrupted an Israeli professor’s class. I have already criticized Musk’s proto-Nazi salute, and his bizarre mix of blatant antisemitism and performative philosemitism is deeply troubling.

But I definitely worry about the impact that Khalil’s arrest last weekend by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents is already having on our precious, rare, tradition of free speech, especially on campus.

This week, the dean of Columbia’s journalism school and a First Amendment lawyer who teaches there told international students they should not publish articles or post anything on social media regarding Khalil’s case, Gaza, Israel or Ukraine. “These are dangerous times,” the dean, Jelani Cobb, reportedly said. “Nobody can protect you.”

Pour yourself another whiskey, because what’s the point of attending one of the nation’s top journalism schools if you can’t publish?

And, really, what’s the point of attending an American university if you cannot participate in campus protests?

Thomas Homan, President Donald Trump’s border czar, described Khalil on Wednesday as a “national security threat,” telling reporters that “Being in this country with a visa or a resident card is a privilege, and you got to follow certain rules.”

Secretary of State Marco Rubio insisted the case was “not about free speech,” and said: “No one has a right to a student visa. No one has a right to a green card, by the way.”

The student days of two polarizing men

Studying in the United States is indeed a privilege, though one of the reasons that the number of international students has more than doubled over the last two decades, reaching a peak last year of more than 1.1 million, is that many of them pay full tuition and thus help subsidize higher education for others. Studying at an elite university like Columbia — and U. Penn. — is also a privilege, and it’s never been only about what happens in the classroom.

The most formative part of my own experience at Yale University was not my history major; it was reporting, writing, editing and leading at the Yale Daily News. And it was covering a campus protest against sexual assault that made me realize my place in the world was as an observer not an actor, which is how I ended up going into journalism instead of politics.

“His mind was elsewhere, focused on getting out of college and becoming what he is now.”Jennifer Gwynne, former girlfriend of Musk

Musk does not appear to have been a campus protester while at Penn. He was a resident adviser who dated a junior in the dorm, a teaching assistant for a computer science course, an entrepreneur who created a software company called Zip2 that provided city guides for newspapers — and a supporter of entrepreneurs, befriending an immigrant cafeteria worker who opened an Ethiopian restaurant. He played chess and did card tricks, according to college friends interviewed by The Daily Pennsylvanian, shunned sports and bars, and was already dreaming about electric vehicles.

“We were two introverted kids who hung out a lot,” recalled Musk’s college girlfriend, Jennifer Gwynne, who in 2022 auctioned off memorabilia from their relationship for more than $165,000. “His mind was elsewhere, focused on getting out of college and becoming what he is now.”

I’ve been struck throughout the week about how little we actually know about Mahmoud Khalil and his time at Columbia. He was clearly a leader of the pro-Palestinian protests, speaking to the media and negotiating with administrators. But unlike many student activists, he does not seem to have posted much about the war in Gaza on social media, making it difficult to assess the Trump administration’s accusation that he is “aligned with Hamas.”

Khalil’s wife, Noor Abdalla, a 28-year-old dentist who is eight months pregnant, told Reuters that the couple met in 2016, when she volunteered for a nonprofit he ran helping Syrian youth in Lebanon, and dated long distance until he came to Columbia. She described him as “the most kind, genuine soul,” and said that during his days in detention, Khalil had been sharing food with other migrants and helping those with poor English fill out legal forms.

He may have been the first immigrant student activist arrested mainly because he was one of the few who did not hide his face behind a mask during demonstrations. Which is unfortunate, since it may make protesters more likely to put on masks, and that definitely helps create an atmosphere of intimidation.

Purim, of course, is the Jewish holiday of costumes and masks. Which helps blur the lines between heroes and villains, regardless of how drunk you are.