Why you can’t judge a record by its cover — even if it’s full of swastikas

‘Hitler’s Inferno’ is a record of Nazi marching songs with a surprising Jewish history

Hitler Youth recruits in a Nazi Party parade prior to World War Two, Berlin, Germany, June 12, 1932. Photo by Keystone View Company/FPG/Getty Images

It hadn’t been my intention to buy a collection of Hitler speeches and Nazi anthems when I walked into a record and book shop in Sedona, Arizona. My browsing first led me to a collection of Jewish fairy tales; my next big finds were two Monkees LPs, the perfect birthday presents for my mom.

It was the thrill of coming across those albums that led me to surf through the rare records bin on my way to the checkout counter, just to see if I could find another hidden gem. When I glimpsed images of swastika banners, I paused.

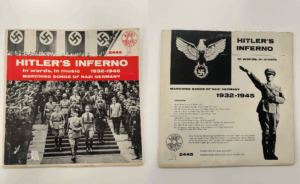

What caught my eye was a standard-size LP, produced by Audio Fidelity Records, with a picture of a Third Reich procession on the front cover. Hitler has just descended a set of carpeted steps, flanked by Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess and Air Force Commander Hermann Göring. A group of military officials is coming down the steps behind them. On either side of the stairs are Nazi soldiers, some offering a salute to the passing group.

On the back of the record, there’s the Nazi War Eagle with its laurel wreath and swastika, and Hitler, thrusting out his right hand. The track listing starts with “Adolf Hitler speaks in Rome. 1937,” and ends with a recording of Nazi defendants, including Göring and Hess, pleading ‘not guilty’ at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trial.

At the bottom, there’s a note:

“Never before has this shocking material been heard in the United States. Most of these songs and speeches were taken from German radio stations after the war. Their joyous quality is frightening, when one thinks of the murder and destruction that followed. It must never happen again in the civilized world.”

I put the record back, and checked out with my fairy tales and Monkees records. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that it was wrong to leave the piece of paraphernalia — even if it was made for educational purposes — to possibly fall into the hands of a Nazi fanatic.

I am not the first person to inadvertently come across Nazi memorabilia and have to decide what to do with it. One man, who’d inherited a Nazi belt buckle from his father, asked The New York Times Magazine’s ethicist how to ensure it stayed out of neo-Nazi hands. The ethicist’s answer: Bury it. Retired attorney Peter Janovsky chose to donate Hitler Youth medals that had fallen into his possession to the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, where they are used to teach about the Third Reich’s indoctrination of German youth.

There are also Jews who purposefully buy these relics. An Orthodox Jew whose grandmother survived Auschwitz paid $50,000 for a notebook that had belonged to Nazi physician Josef Mengele. Michael Bulmash, a retired Jewish clinical psychologist, has bought dozens of relics, including labor camp patches and propaganda posters, which he has donated to Kenyon College, his alma mater, for the Bulmash Family Holocaust Collection.

Haim Gertner, former archives director of Yad Vashem, told The Washington Postthat some Nazi artifacts are worth preserving if the owners want to make sure the Holocaust is never forgotten. But to sell the items for the highest profit, he said, “is incorrect and even immoral.”

That hasn’t stopped the for-profit Nazi relic industry from flourishing. Hitler’s paintings (and fakes) have sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and Nazi relics have been looted from museums, likely to be sold to collectors. You can also find Nazi knick-knacks on eBay. At the end of a Torah learning fellowship I did in college, the lead rabbi passed around a Third Reich coin he had bought off the website. The intention was to instill pride in us, that despite the Nazis’ efforts, the Jewish people and our traditions had outlived their “empire.”

This message played in my head when I decided to go back to the store to buy the record. For me, a Black Jew, isn’t possessing a physical copy of the speeches of a man who never wanted me to exist a sort of revenge? (And purchased with the money I made writing for a Jewish publication, no less.)

You also never know what you might learn from these objects. When I looked up Audio Fidelity Records online, I learned that it had once been owned by Sidney Frey, who had previously released Jewish music collections under his label Kinor Records. Frey, who was Jewish, was an early pioneer in recording, with a special interest in producing sound effects and preserving historic audio. This included music, such as Confederate marching tunes, but also ambient noise like steam and diesel trains, which were starting to be phased out by the late 1950s.

He also distributed the album “What Is Torah?,” a collection of cantatas by Rabbi Ira Eisenstein and his wife, Judith (born Judith Kaplan, she was the first woman to be bat mitzvahed in the United States). Frey produced records until health complications forced him to sell Audio Fidelity in 1965. He died three years later at the age of 48.

Hitler’s Inferno was originally produced in 1953 and sold around the world. The album was exported to West Germany, where it sold well until its sale was effectively banned by a court in Dusseldorf in 1959. Because the public display of the swastika was illegal in West Germany at the time, the court determined shop owners could not put the album on shelves. The record also found some popularity in London during March 1965, according to a report by The Buffalo News. A store manager said buyers included students, collectors, academics and “odd types.”

Not long after it was banned in Germany, someone pirated the album and replaced the speeches that preceded each track condemning the violence of the Nazis with antisemitic commentary in German. Mention of the album also appears in the Forward’s archive. On Jan. 16, 1960, we reported that the record was found in the possession of neo-Nazis who were arrested by the NYPD for allegedly defacing synagogues. According to our report, the accused also planned to create an organization called the “National Socialist American Renaissance Party” to advocate for the deportation of Jews to Israel. If that campaign was unsuccessful, they told detectives, they would use violence to rid America of Jews. Hitler’s Inferno sat among their swastika paraphernalia and Nazi membership cards.

Frey told The State Journal, a newspaper in Lansing, Michigan, that the record “was intended to illustrate how music can be used as a force for evil as well as good” and be a “castigation of the Nazi regime.”

In the end, seeing how the album was appropriated in the past, I’m glad I took a copy off the shelves. I considered donating the record to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, but they already have one. For now, it’s stashed in a black bag under my bed. The next big question — what do you think I should do with it?