In Israeli Politics, The Future Is Female

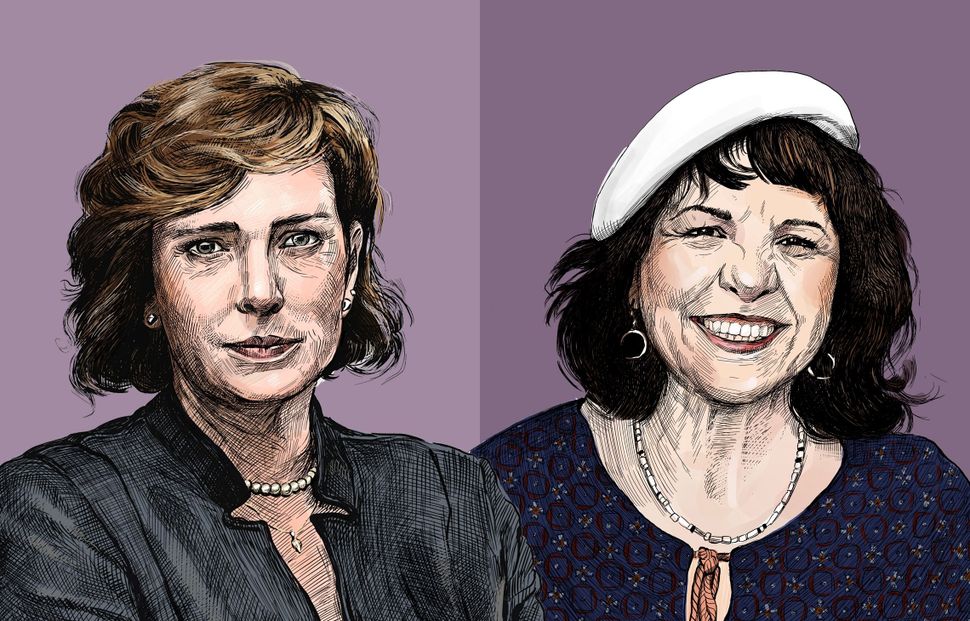

Image by Anya Ulinich

The faces on the walls of the second floor of the gracious municipal building in Haifa tell a story of male authority. Lining the corridor are portraits of the mayors of modern Haifa, beginning with Hassan Bey Shukri, a Muslim appointed by the Turks in 1914, and continuing with his eight successors right up to Yona Yahav, who served for 15 years until losing re-election last fall.

Whenever the tenure of Yahav’s successor ends — in five years, or 10, or another 15? — a 10th portrait will be added. But this time, for the first time, it will be of a woman.

Einat Kalisch-Rotem, 48, became the first woman elected mayor of any of Israel’s three largest cities in a sweeping victory in the October 30, 2018, municipal elections. And she wasn’t the only one to break through the glass ceiling of Israeli politics.

Ninety miles southeast of Haifa, Aliza Bloch, 51, was elected the first woman mayor of Beit Shemesh, a sprawling city better known for the bitter protests by its growing ultra-Orthodox population than for its progressive politics.

All told, although the percentage of women candidates for local government increased only modestly, women’s success at the polls was dramatic. The number of women mayors doubled, from 3 to 6, as did the number of women on local councils.

This comes at a time of record female participation in the Israeli Knesset, where the number of women jumped fivefold in the past three decades.

The national political landscape in Israel appears as calcified as an ancient archaeological remain buried in the desert, with the same parade of would-be leaders grouping and regrouping into an endless array of parties and coalitions before the April 9 elections.

But one rung below, on the municipal level, a quiet transformation is taking place.

It echoes the dramatic number of women who ran in America’s midterm elections and propelled a historic surge in the U.S. Congress — with one significant difference: The American trend is overwhelmingly one-sided. The number of Republican women in the new House of Representatives, for instance, is the same (13) as it was 30 years ago. The number of Democrats swelled to 89 from 16 over that same period.

In Israel, by contrast, women were victorious across the political spectrum, from Labor to Likud to Jewish Home. In some communities, like Beit Shemesh, women candidates even worked together across party lines, accessing networks they had built over years of behind-the-scenes activism in their deeply gendered society.

“On election night, in the past, everything was for men,” Rena Hollander, an Orthodox lawyer who now is the first and only woman on the Beit Shemesh city council, told me. “This year, after Aliza won, the whole city center was dancing in circles, and the men were standing around, staring. Then the men formed their own circle around her. I suddenly felt — wow, mamash, we came out from darkness to light.”

**

Superficially, Kalisch-Rotem and Bloch have little in common beyond gender. The new mayor of Haifa is a staunch secularist in the Labor Party; the new mayor of Beit Shemesh is Orthodox and allied with the religious nationalists of Jewish Home. Clothing is a profound marker of identity in Israel; Kalisch-Rotem wears pants, Bloch wears modest dresses and sports a jaunty beret to cover at least part of her dark hair.

But on a deeper level, there are commonalities. Both women represent different aspects of the immigrant experience — when women not born of privilege strive to educate themselves (they both have a doctorate) and commit to service-oriented careers before they enter politics. Both Kalisch-Rotem and Bloch ran a nontraditional campaign and had to overcome blatant skepticism about their chances as women leaders. They are fierce champions for the distinctiveness of their cities and the need for coexistence — in Haifa, between Jews and Arabs, in Beit Shemesh, between the ultra-Orthodox Haredim and everyone else.

And they are able to draw upon a certain Zen approach to governing.

Bloch, a former school teacher, said that she deals with loud, angry male political counterparts like she would with an unruly classroom, by waiting out the anger and demonstrating who is in charge. “I say to them, ‘Why are you shouting?’ When you come from the education world, you have patience. I know that after two or three or four meetings, they will see things are different,” she told me.

Kalisch-Rotem has a black belt in karate and finds her training essential in her new job.

“You do martial arts from morning to night. It’s not physical; it’s mental,” she told me. “You know how to react to the punches. You decide when you want to hit back and when you want to absorb it and go on your way.”

**

Kalisch-Rotem’s parents arrived in Haifa from Poland just after Israel declared its independence. They built their lives along with the state. Kalisch-Rotem grew up in what she called “social housing,” in what we might call a blue-collar neighborhood. She made her way to the Technion for undergraduate and graduate degrees, and she completed her doctorate in urban planning in Switzerland. She owns an architectural firm.

This background informed her politics since she first ran for mayor, and lost, in 2013. “Haifa grows poorer every year; it loses youngsters, the educated, its institutions. It is losing economic strength and vitality. It became very difficult to see the city in the process of dying,” she told me during a lunchtime interview in her office, leaving a plate of small sandwiches largely untouched.

“It hurts. I really love the city. It is the most beautiful in Israel, the most European, the most cosmopolitan. The architecture, the history. Mountains, beaches. Everywhere you see the bay,” she went on. “I know many cities around the world manage to renew themselves. I know how this process is done.”

So Kalisch-Rotem became an activist and eventually led the opposition in Haifa’s city council, all the while developing and speaking about plans for urban renewal. It was a harsh, cold experience. “I didn’t expect to get so many backs turned against me,” she said. “All the doors were slammed in my face. That was shocking. Everybody decided to do everything in their power to make sure I dropped dead, politically speaking.”

An Audience With The Mayor: Forward editor-in-chief Jane Eisner sits down with Einat Kalisch-Rotem for an interview. Image by Office of the Mayor

Was this because you were a woman, I asked. Or because you were in the opposition? Or because you were challenging the status quo?

“Yes. Yes. Yes!” she exclaimed.

Mayor of Haifa: Einat Kalisch-Rotem, 48, became the first woman elected mayor of any of Israel’s three largest cities on October 30, 2018. Image by Anya Ulinich

She argued during last year’s campaign that Yahav’s administration spent too much time and money trying to turn Haifa into a mini-Tel Aviv — “breads and circuses,” Kalisch-Rotem said — while she claimed that poverty grew, neighborhoods struggled and good jobs were harder to find.

“Haifa has its own character,” she insisted. “We need to help cultural entrepreneurs to live here and produce here.” Her campaign tagline: We have to stop looking south with envy and start leading the north with pride.

It worked. She won easily, with 56% of the vote.

Now comes the grueling task of governing. The day I visited, Kalisch-Rotem was rushing from one meeting to the next, declining all other requests for interviews, still obviously adjusting to the new role. She already had stumbled onto a political firestorm over the appointment to her coalition of a radically outspoken Arab member of the Hadash party; he stepped aside for a more moderate colleague, but the mayor was adamant that the party be represented.

“Haifa is not Israel and Israel is not Haifa. There has always been a mixture of Jewish and Arab people here,” she said. “We all live together. There is a big serenity here. Maybe it’s because of the bay, the trees, the turquoise beach. We eat hummus in Arab neighborhoods, buy in their markets, use the hospital and community centers together. We are friends.”

She told me that after her second child was born, she hired a Muslim nanny. Her Jewish friends from elsewhere said she was crazy. “Why not? She is the best for me,” was her answer. “I trust her completely. Israel cannot understand this mentality.”

**

Although she won her election by only a whisker, Aliza Bloch became the subject of instant fascination in Israeli politics simply because she won at all. Beit Shemesh is an expanding set of interlocking neighborhoods, and some are so tightly controlled by the Haredim that a few years ago, an 8-year-old Orthodox girl was spat on as she walked to school, by men who claimed she was dressed immodestly.

Mayor of Beit Shemesh: Aliza Bloch is a former schoolteacher. Image by Anya Ulinich

Graffiti calling women “whores” still is visible on some streets. So is the staircase with a railing in the middle that designates one side for men, another for women.

Which is why Bloch’s dramatic victory over the ultra-Orthodox incumbent seemed so improbable. The fifth of seven children — and the first born in Israel — of parents who came from Morocco, she was raised in an immigrant absorption center by a family of strong women and fervent Zionists. She has an undergraduate degree in mathematics and a doctorate in education from Bar Ilan University, and she moved to Beit Shemesh with her husband because, she told me, they wanted to raise their four children in a diverse environment: “Kippah and not kippah, from Ethiopia, Russia, United States. To grow up with everybody not like you.”

She, too, ran for mayor, and lost, in 2013, and tried again five years later because tensions between the Haredim and other residents had grown even worse. “All the people in our country think Beit Shemesh is a war city,” she told me, appearing not yet to be comfortable behind her large, official desk. “We must stop this image. We must stop this war. We must learn to live together.”

Bloch focused her campaign on schools, transportation, infrastructure, employment — careful not to emphasize her breakthrough gender role. “I am woman, yes, but it’s not my flag! I’m Aliza, vote for me” was how she framed her message.

Her challenge, in part, is managing expectations. A cadre of women activists in Beit Shemesh laid the groundwork for her dramatic, razor-thin victory, and after meeting with a group of them I sensed their eagerness to claim some credit. “She would not be able to get to her position without our activism over the years,” Hollander said.

And yet they also recognize that Bloch’s patient, cautious, cheerful style — honed by years in the classroom — fits their male-dominated community. “Aliza looks at herself as a mayor who happens to be a woman, and that’s how they relate to her,” said Etti Suissa Ben-Ami, a journalist and social activist. Then, as if to indicate that the women know differently, she added, “She’s like 10 men.”

**

Of course, Israel is no stranger to strong women leaders. You can prove that point with one word: Golda.

More recently, Tzipi Livni served as foreign minister and leader of the opposition. Ayelet Shaked is emerging as a charismatic figure of the political right.

But the change now seems to be broader and deeper. “You hear voices in the last decade you didn’t hear before,” said Chen Friedberg, a research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute.

That’s a reflection not only of global trends, but also of institutional incentives. Four years ago, local election law was reformed to give parties financial bonuses if at least one-third of their slates are women. Researchers can’t prove a direct correlation with last fall’s electoral victories, but they believe the reform certainly played a part.

Lagging behind these developments are communities dominated by Haredim and Arabs, where women’s roles have traditionally been highly circumscribed and regulated. Even there, however, there is movement. In the last municipal election, 19 Arab women were elected to municipal councils, according to IDI.

And even if Haredi women are not yet striding into mayors’ offices, the symbolism of victory for someone like Bloch is profound. As Ofer Kenig, another IDI research fellow, told me: “Just think of the young girls in Beit Shemesh who now have a woman mayor. This is substantial!”

Kenig’s insight echoed a conversation I had one morning in Jerusalem with Fainy Sukenik, a Haredi activist who created an organization advocating for divorced and single women in the ultra-Orthodox world. She told me about Rav Chaim Kanievsky, a leading Haredi rabbi who was persuaded to throw his support behind Kalisch-Rotem in Haifa. And about other members of her community, who voted for Bloch in Beit Shemesh — or who stayed home that day, depriving her ultra-Orthodox opponent of their votes.

Just pause for a moment and take in the profound change this represents. The symbolism is certainly not lost on Haredi women like Sukenik.

“The rabbis are always saying the women are not supposed to be in politics. How come?” Sukenik asked rhetorically. “How can you stand and deliver these two messages on these women, and the Haredi women are not good enough? There is hope now for many other changes.

“I want to fix something that is broken in my society. You should see us. We have a voice. We are here to stay.”

Contact Jane Eisner at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter, @Jane_Eisner. Sign up here for her weekly newsletter, Jane Looking Forward.