Visiting My Ultra-Orthodox Brother, A World Apart

Ultra-Orthodox Jews pray over month-old infant Yehoshua Rosenboim, who lies in a silver bowl on the rabbi’s table, as they perform the Redemption Of The First Born ceremony at the Lalov synagogue July 31, 2008 in Bnei Brak, Israel. Image by David Silverman/Getty Images

My daughter and I step out of the car into the dry heat: Jerusalem, midday, August. An oven on Turbo Grill. She wears a maxi skirt to her ankles and beseeches me to pull down my just-above-the-knee dress and tie decorative ties near my neck to cover any trace of cleavage. I poo-poo her; I’m fifty-one, she’s eighteen. I’m comfortable as a secular Jew, whereas she’s at the peak of the strive-to-blend-in stage. But she forgets, between visits, that no matter what we do, how we dress, we stand out as other, as different, as ‘less than’ in my brother’s world.

We open the front door of the yeshiva, where a young man quickly escorts us back outside and points in the direction of the hall. “Hall” is an exaggeration—it’s a window-less room, basement, four walls with two doors, one for men, the other for women. As soon as we enter the second door, eyes turn. Women with elaborate scarves or wigs over their heads hide every strand of hair. Girls with long-sleeve dresses resemble Laura’s on “Little House in the Prairie” adorned with ruffles and lace. They all wear thick stockings despite the desert’s grip.

I scan the room for my sister-in-law, niece, oldest nephew’s wife, any familiar female face that can vouch for us; we’re not lost. We belong, even if we look like interlopers.

“Hey, you came!” Niece number two screeches, an exclamation point of surprise in her voice. In spite of living one hour north, we don’t see each other often. Visits are reserved for special occasions like today.

Today is the pidyon haben—a ceremony celebrating redemption of the first-born son from his birth-state—for my nephew’s new baby, my middle-aged brother’s fifth grandchild. Assuming my brother’s six children remain uber-religious, marry and multiply, they’ll create an empire.

“Did you see the baby?” Niece number three asks. Thirteen and a half, she is head to head with her seventeen-year-old sister and me. They point at a sterling silver soup tureen large enough to serve hundreds of guests at a palace ball in some other century.

A one-month-old infant decked out in a long-sleeved, white onesie, adorned in gold jewelry lent by the guests and surrounded by little toile sacks containing a garlic clove and two sugar cubes, all symbols of luck and health and other bubbe-meises or grandmotherly fables, sucks on a shiny blue pacifier and sleeps in oblivion, resembling a Hans Christian Andersen character. His name is Yitzhak Shlomo.

When my daughter asks the meaning of it (the tureen, the jewels, the pouches), some well-intentioned stranger explains it’s minhag or tradition (in their Haredi, Ultra-Orthodox community), not halacha or law based on the Torah. We nod as if we understand their reasoning and rituals, but we don’t. My brother and I were raised as assimilated Reform Jews in America, and while my children grew up observing some of the laws of the Sabbath, they’ve stopped since moving to Israel.

“So, what’s new?” I ask my nieces.

Number two juts out a hip and says, “Well, this is all great, but I’m not interested. First, I have to go to college then graduate school then get a job then get married then have babies. Or maybe I’ll get married and then find a job. Oh, I don’t know.” She throws up her hands.

A dreamer, she has a spunk and restlessness that sets her apart from her clan. Then again, her older sister said the same thing at her age. Now, twenty-two, she’s married with a one-year-old and another en route.

My sister-in-law approaches. “Yeah, you made it,” she says with a heartfelt smile.

Three weeks ago, for the baby’s circumcision ceremony, we didn’t make it. We left our house in Raanana early Friday morning and drove seventy-five minutes to Jerusalem despite traffic and police, road closures and security checks. We drove with our Waze’s guidance toward a parking lot outside one of the eight gates of the Old City for the gathering in the Churva synagogue in the Jewish quarter. We drove through East Jerusalem to the base of the wall between the Temple Mount and Damascus Gate, two hotspots that often make front page news, only to be barred entry, turned around, by dozens of border police preparing for protests because of metal detectors set up outside their holy site. We drove for two and a half hours round-trip without seeing the family.

Today, I want to see them. Fifteen months ago, my then nineteen-year-old nephew and his eighteen-year-old wife were fixed up by a matchmaker and wed two months later while we traipsed through India, a trip we’d booked long before their first date.

My nine-year-old nephew, the youngest, runs up to say hi. He’s the only male family member allowed to cross the mechitza — a make-shift partition between the sexes — since he’s under the age of Bar Mitzvah. I lean down to kiss his cheek. He pulls back. In their house, our physical contact is allowed (his brothers refused as soon as they turned thirteen), but he’s old enough to distinguish between public and private.

“Seriously, that’s it? No more kisses?” I tease.

Niece number two giggles and grabs him, planting one on his cheek, saying, “Look, I’ll do it for you.”

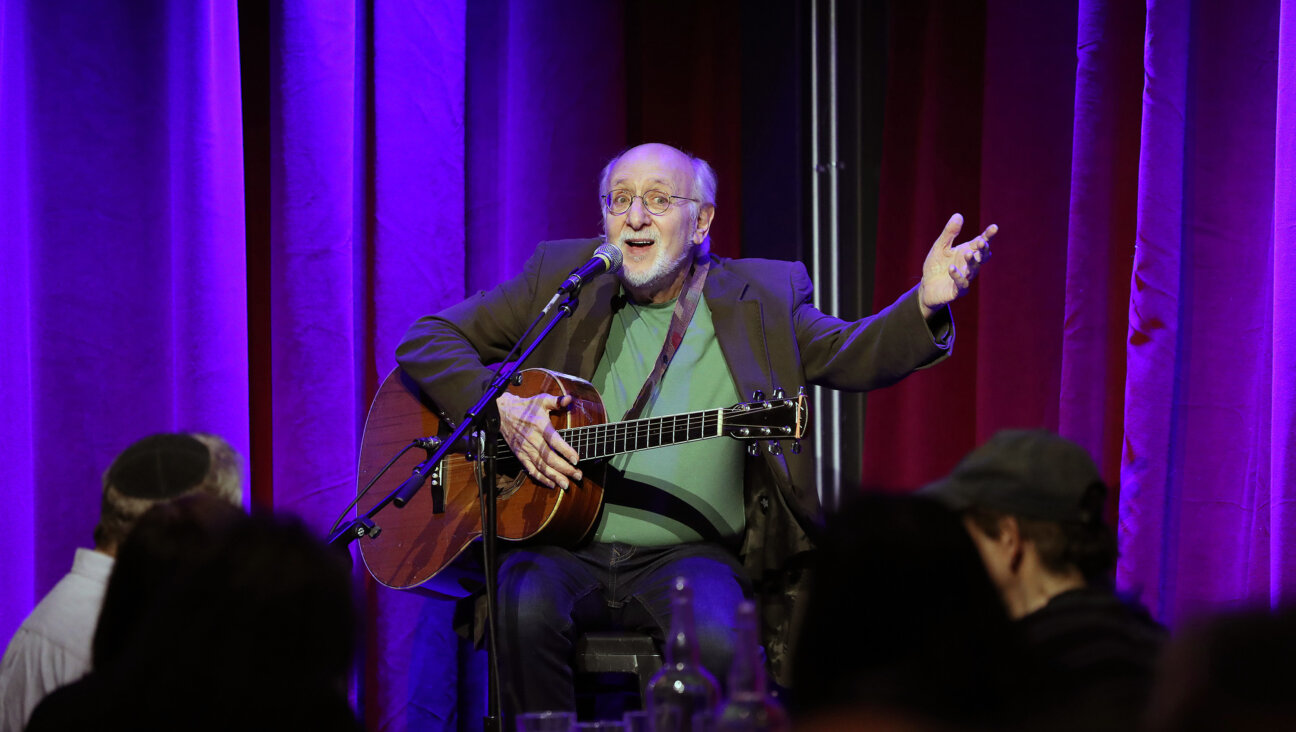

The women mill about the room, kvelling over how cute, how quiet, how tall, how small the baby is until dozens of males, all dressed in black pants, white button-down shirts, black blazers, black kippahs, and black top hats start singing. Some sport long peyot dangling next to their ears; others, like my nephews, tuck them behind, out of sight. White tzitzit fringes hang over their pants. Every one of these outward, visible symbols of purity and devotion to Hashem, as they refer to God, has its own meaning. The women line up on our side of the room, peering through slats. A young man, perhaps one of the mother’s twelve siblings, approaches to whisk Yitzhak away in his dish to their side on the road toward redemption. If I didn’t know any better, I’d think I’d stepped foot onto a Paramount movie set for “Yentl.”

I stare at the men, searching for my newly married nephew, but they all look the same, swaying their bodies in joyful ecstasy, high on prayer.

My brother embraced this fervent form of Judaism three decades ago. For the better part of those years, I railed against him and his choices. But now, seeing his offspring who don’t criticize me for not covering my hair or judge me for acting more goyish than Jewish, I know better. My three children are their only first cousins; I’m their aunt. If my youngest nephew rebuffs my kiss, I will respect his wishes even though it makes me feel less connected, like an outsider.

Because I understand — and one day he will too — that we all yearn for the same thing.

Jennifer Lang’s essays have appeared in Under the Sun, Assay, Ascent, The Coachella Review, Hippocampus Magazine, and Full Grown People. Honors include Pushcart Prize and Best American Essays nominations and finalist in 2017 Crab Orchard Review’s Literary Nonfiction Contest. Find her at http://israelwritersalon.com and follow her @JenLangWrites as she writes her first memoir.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO