New Kind of Passion in an ‘Alpine Jerusalem’

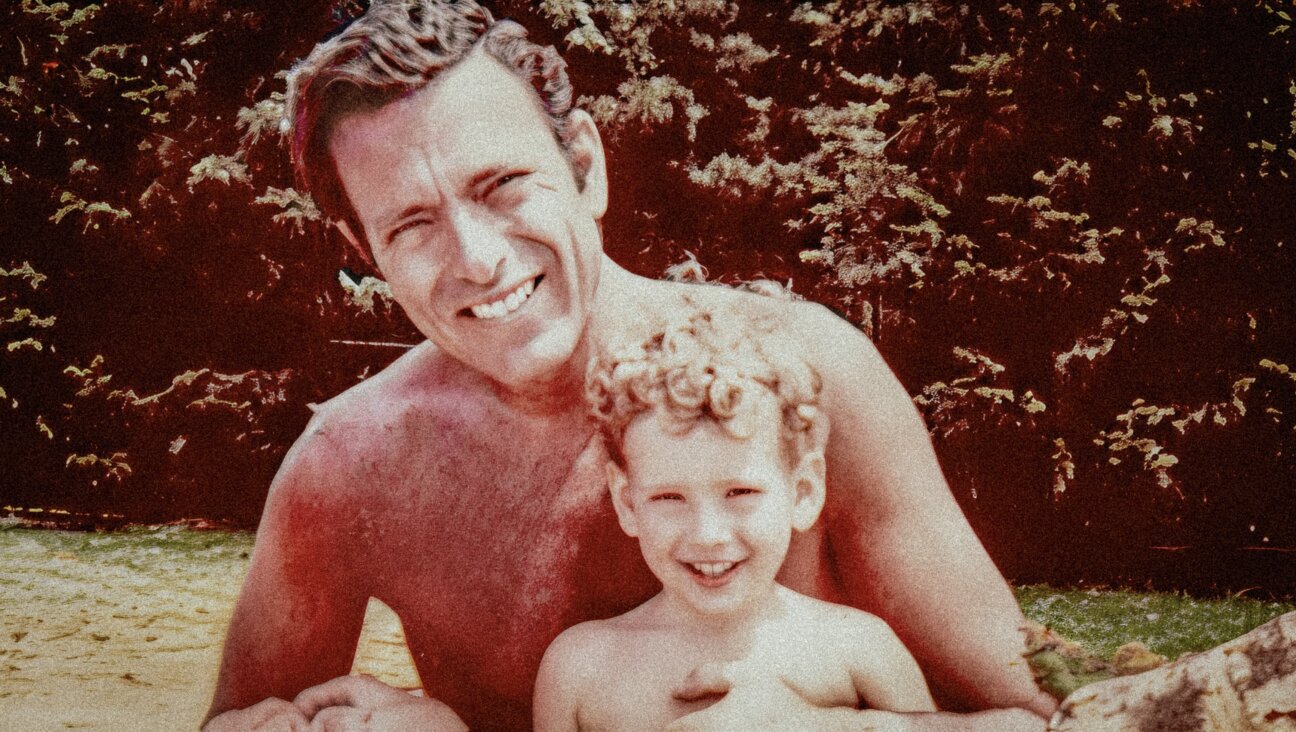

It Takes a Village: Andreas Richter, center, rehearses the role of Jesus with other local residents in a centuries-old passion play that critics say retains antisemitic features. Image by SEBASTIAN WIDMANN/AFP/GETTY

A Modern Jesus: The Oberammergau Passion play has been staged about every 10 years since 1634. Frederick Mayet (with bread) portrays Jesus in this rehearsal of the Last Supper. Image by GETTY IMAGES

It was during the intermission in Oberammergau’s controversial, once-in-a-decade Passion play that I met Jesus for a cup of coffee.

Sh?ma israel: Jewish elements, such as Jesus entering the Temple holding aloft a Torah scroll, have been introduced. Image by GETTY IMAGES

A public relations man at the Münchner Volkstheater when he’s not onstage, Frederick Mayet, 30, has the long, dark-blond hair and bushy beard of a Nordic Jesus portrait hanging on the wall of a rectory somewhere in Kansas. But asked to describe the essence of the play whose alleged antisemitism has been a point of tension with Jewish organizations for decades, Mayet, sipping a cappuccino, described the Passion play first and foremost as “an inner Jewish story” that dramatizes religious conflicts within Jerusalem during the Roman occupation.

An Oberammergau resident and nonprofessional actor, like all the cast members, Mayet was one of 50 villagers who traveled to Israel last September on a research trip to prepare for the play, accompanied by a theologian from the Vatican. Mayet, one of two actors who alternate in the role of Jesus, considered the trip and the ensuing discussions essential to preparing for the part.

“I feel a great responsibility in this role, knowing that every time I go onstage, there are nearly 5,000 people watching me. I never look at the audience,” said Mayet, who appeared in the 2000 production as John.

If Mayet is consumed by this role, he is not alone. The play can be said to envelop Oberammergau itself, a small Bavarian village that likes to think of itself as an Alpine Jerusalem. Wandering around, you see houses painted brightly with biblical scenes, and streets with names like Mannastrasse, Judasstrasse and Magdalenagasse. Villagers greet each other with “Grü[ß Gott!” a Bavarian salutation that means “Greet God.”

May 15th saw the opening of the 41st production of the Oberammergau Passion play. The event, nearly six hours long, will run for more than 100 performances until October, in a theater that can seat 4,700, almost the village’s entire population. Roughly half the villagers are involved in creating and realizing the play.

Prior to arriving here, I knew the name Oberammergau mainly from high school history class at home as one of the most infamously antisemitic of theatrical spectacles. My reading material on the trip in included the Anti-Defamation League’s recent statement that the Oberammergau play “continues to transmit negative stereotypes of Jews.”

And so after my flight and various train connections, I was quite astounded to witness an intelligent, beautiful and moving work of art that didn’t smack of the racist accusations historically leveled against it.

The production has been staged about once a decade ever since its citizens made a vow in 1634 to perform a play in perpetuity if their village was spared the ravages of the Plague. It is undeniably true that the play was virulently antisemitic through most of its history, and that it gained an extra dose of notoriety after Hitler endorsed the 1934 production. In Oberammergau, the Nazis found precisely the sort of grass-roots peasant drama that was ideal for their racist ideology.

After World War II, American Jewish intellectuals — including Arthur Miller, Leonard Bernstein and Lionel Trilling — signed a petition condemning the play’s portrayal of Jews. International outrage followed from such German and European literary figures as Günter Grass, Heinrich Böll and Paul Celan.

Around the same time, the Catholic Church demanded changes to the play, to bring it more in line with Nostra Aetate, the landmark 1965 declaration from the Second Vatican Council proclaiming that the Jews, as a people, were not responsible for the death of Jesus Christ. When changes were not implemented for the 1970 production, the Vatican withheld its religious approval, known as the Missio Canonica. Then, in the 1970s, Oberammergau invited representatives from Jewish organizations, including the ADL and the American Jewish Committee, to participate in dialogues about script revisions.

Amendments to the current script need to be approved by Ludwig Mödl, a theological adviser appointed by the archbishop of Munich and Freising. In his introduction to the script, Mödl discusses these alternations: “Jesus, the Jew, sought to renew the religion of his fathers, a religion built on the foundation of the law and the prophets.”

Christian Stückl, the play’s director, also stressed the link to Judaism. “Jesus never lived as a Christian, but rather from the day he was born to the day he died he lived as a Jew,” explained Stückl, a director of note who runs the Münchner Volkstheater. Reinforcing this perspective, there is a new scene where Jesus enters the Temple with a Sefer Torah, holds it aloft and recites the prayer “Sh’ma Yisrael,” which is answered by the entire crowd onstage in Hebrew. During the Last Supper, Jesus says Kiddush and Hamotzi in flawless Hebrew, and John asks, “Why is this night different from all other nights?”

The infamous blood-oath from the Gospel of Matthew, in which the Jews collectively demand that responsibility for Jesus’ death “be upon our heads and the heads of our children” during Jesus’ sentencing before Pilate, was removed for the 2000 production and remains cut. And the Jewish priests haven’t worn horn-shaped hats since 1984.

In previous stagings, the Romans didn’t appear until the arrest of Jesus at Gethsemane. Now they stand guard at the gates when Jesus makes his entrance to Jerusalem in the first scene, making it clear who is really in control. There are extended theological debates between the members of the Sanhedrin, as well as an expanded role for Pilate, who now threatens Caiaphas, the Jewish high priest, with the might of the Roman army should there be an insurrection. Along with Pilate, Caiaphas is clearly the main villain, but there are enough dissenting Jewish voices to make clear that the High Priest doesn’t speak for all the Jews.

Perhaps most surprising is the amount of sympathy for Judas, who is portrayed as wanting to facilitate dialogue with the priesthood and is duped into betraying Jesus. It is one of the best roles in the play. When Judas understands that he has been manipulated, he storms the Temple, demanding Jesus’ release. During the wrenching suicide scene that followed, people around me were wiping tears from their eyes.

Walking around the village, you hear various accents of English and German, but also French, Spanish and Japanese. Most of the tourists tend to be older and come here on package tours.

While I was talking with Stückl, a woman approached and thanked the director for doing such a wonderful job of clarifying the connections between the Old and New Testaments, specifically the play’s Hebrew lines. Another woman from Arkansas told me about the great Passion play in Eureka Springs in which Jesus actually flies. To many people, the play seems less about Jesus and more a rare chance to experience a legendary tradition.

What is lost in the whole discussion over alleged lingering traces of antisemitism in this Passion play is that the production is a remarkable communal feat and an artistic triumph. Much of the production’s power derives from the lush oratorio-like music and the tableaux vivants of Old Testament scenes. I have a much harder time swallowing Wagner’s antisemitic caricatures and religious mysticism than I had with sitting through this equally long spectacle, with its harmonious alternation between drama, music and meditation. For this reason, it is unfortunate that many of the play’s critics have never seen the actual production of this Passion play.

For instance, a recent 16-page report from the Council of Centers on Jewish-Christian Relations, which was based on the 2010 script alone, objects that the play still makes use of “elements that are historically dubious” that stem from the Gospels. It seems unfair to evaluate the script by casting aspersions on the truthfulness and accuracy of Christianity’s sacred texts. Will no amount of revision suffice to silence the play’s critics?

Otto Huber, the play’s second director and dramatic adviser, and possibly the person most knowledgeable about its history, sought to persuade the ADL’s national director, Abraham Foxman, before the 2000 production that the play’s transcendent theme was about love and redemption. But as related in James Shapiro’s 2000 book “Oberammergau: The Troubling Story of the World’s Most Famous Passion Play,” Foxman responded: “If you want to give me love and understanding, there are a lot of other Christian subjects. Give me another play; if it’s about a Crucifixion in which the Jews kill Christ, you can never clean it up enough.”

Frustrated with the ongoing criticism, Huber expressed his own hopes for the future Passion plays. “I think it’s very hard to tell this story in a good dramatic way,” he said. “It would also be more exciting if the theology would be clearer.” Huber is down to earth about the limitations of the script: “Maybe there can be a play where it’s not only [from] the Bible. We could focus more on the great themes of humanity.”

But he added, “I don’t know if Jewish theologians can help us.” Perhaps a little naively, Huber wishes for involvement from Jewish organizations with a real interest in forming a partnership, rather than in patrolling and monitoring. “I would prefer a spiritual dialogue rather than a dialogue between a policeman and a criminal,” he said bluntly.

Contact A.J. Goldmann at [email protected]

Listen to a clip of the Shema from Oberammergau’s Passion play:

Listen to a clip from the living tableau of the binding of Isaac in Oberammergau’s Passion play: