Speaking Each Other’s Language

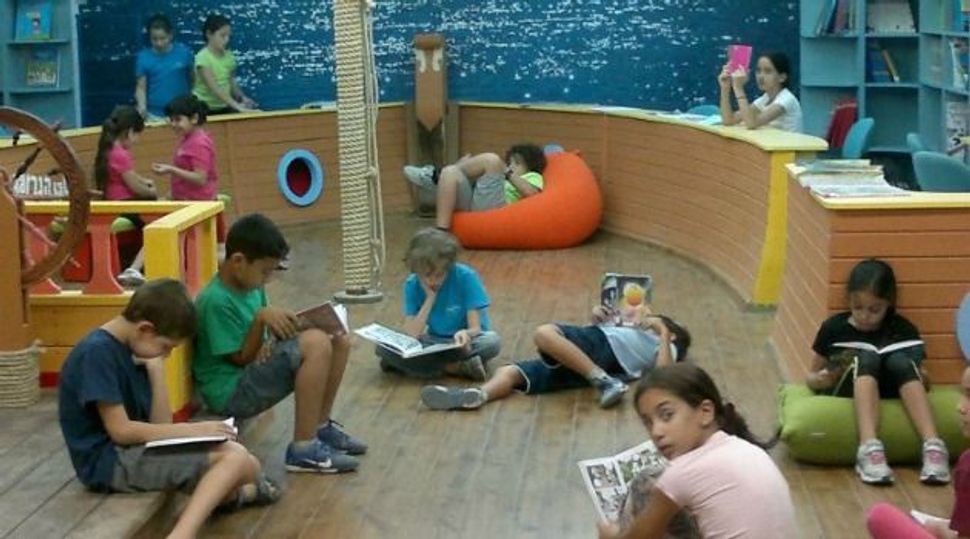

Shelter: The Hagar school?s library doubles as a ship-themed bomb shelter. Image by Courtesy Hagar

Against the recent backdrop of violence in Israel and Gaza, one primary school in the southern Israeli city of Beersheba is attempting real coexistence between Arabs and Jews.

The Hagar school isn’t aiming to solve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or to achieve peace in the Middle East. The parents and teachers involved simply want to bring cooperation and understanding to their local community, all while providing a quality education for their children. And it’s more than just talk: Hagar boasts some of the highest test scores in the Negev.

Started in 2007 by Jewish and Arab residents of Beersheba, the school, which is run by the nongovernmental organization Hagar: Jewish-Arab Education for Equality, offers a bilingual Arabic-Hebrew curriculum. It also has an affiliated day care and kindergarten.

The NGO’s executive director, Hagit Damri, is a Jewish woman of North African descent and has two children in the school. As she sees it, the goal of Hagar is to cultivate some level of normalcy in day-to-day Arab-Jewish interactions in a region where 30% of the population is Arab.

“When we started,” Damri said, “we saw a world and saw part of Israel… [in which] most [Jews and Arabs] never met — really met — in person…. We see each other, we just pass through each other; it’s like we’re invisible to one another, like we live in parallel universes. And sometimes we see each other as threats, and sometimes we don’t see each other at all.”

Public primary schools in Israel are categorized as either Arab, Jewish or religious Jewish schools. While Jewish students are welcome to attend Arab schools, and vice versa, few families make that choice. With this de facto segregation in place, Arab and Jewish children grow up learning in two different languages, with few opportunities to interact.

The founders of Hagar — a group of concerned Arab and Jewish parents — didn’t want that for their children. So in 2007 they launched the first stage of their educational system, opening a pre-K and a kindergarten. In 2010, the Beersheba municipality provided them with a building for their primary school, and they received approval from the Israeli Ministry of Education.

Damri and the school’s principal, a fluent Arabic speaker named Smadar Peretz, are both Jewish. The NGO’s board of directors, which makes most of the major decisions about the school, is split evenly between Arabs and Jews.

Initially, Damri said, “it was very hard to recruit. People were suspicious.” But soon word spread about the school’s ideology of coexistence, and the quality of the education. Today, Hagar has 220 students, the majority of whom are from Beersheba, with some commuting from the surrounding areas, including Bedouin villages and affluent suburbs. The Arab students are all Israeli citizens and come from a variety of backgrounds, including Bedouin and Palestinian.

Each class is limited to 25 students and is split evenly between Jews and Arabs and boys and girls. The classes also have two teachers, one a Hebrew speaker and the other an Arabic speaker. All books, displays and lessons are bilingual. Most schools in Israel usually run six days a week and let out at about 1 p.m., but Hagar has an extended day, until 4 p.m., to help out working parents. Although the school has a government-mandated core framework to follow, it develops its own curricula and teaching materials with the help of a pedagogical consultant. Rather than utilize neutral language, the school attempts to acknowledge the respective narratives of Palestinians and Israelis.

For Arab parents, Hagar’s draw is particularly strong. Without a single Arab school in Beersheba, they can send their kids either to a local Jewish school, where they might feel like outsiders, or to an underperforming Arab school in one of the nearby Bedouin villages.

Afnan Abu Taha, an Arab lawyer on Hagar’s board of directors and a parent of two students at the school, said she chose Hagar because it offers her daughters the best opportunities. Having attended an Arab school, she recalls the challenges she faced — both academic and social — when she entered university. “To feel that they are part, that they are respected, that they are accepted, they are taken into consideration. This was the most important thing to me,” she said.

“I think that it’s a better school, and I like what happens here,” said Jewish parent Sigal Tovbin, who has three children in the school and is also Hagar’s enrichment coordinator. “You’re not going with the same children all the way through to the army.”

Hagar is one of five schools in Israel with a bilingual peace education curriculum. The school at Neve Shalom/Wahat al-Salam (Oasis of Peace), founded in the 1980s, was the pioneer. Hand in Hand: Center for Jewish Arab Education in Israel came next, in 1997. Now a network of three schools, Hand in Hand helped create Hagar in Beersheba. Hagar is the only school of its kind in the Negev, and is part of a greater movement to culturally and economically revitalize the region.

Zvi Bekerman, an education professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has been studying bilingual schools in Israel for more than a decade. “In a society like ours,” he said, “the existence of these schools is of tremendous importance, because at least they show the possibility of some type of integration… between populations considered to be in conflict and tension.”

But Bekerman says the schools also hype their coexistence programs at the risk of ignoring their academics. “There’s an inclination to look at these schools in a romantic way,” he said. “You hear they put Palestinians and Jews together, you want to say peace, tolerance, recognition — and you forget that they’re schools. That’s bad. Never forget that they’re schools.”

For now, at least, Hagar appears to have reached a balance between ideology and high scholastic standards. Features like small class sizes, low teacher-student ratio and high parent involvement have led to impressive results. Students at the Hagar School score an average of 91% on Meitsav (a standardized test), compared with an average of 70% in the Negev.

But it’s not all sunshine and roses at Hagar. National holidays are particularly tough for students and faculty alike. The Israel Defense Forces’ Memorial Day, for instance, is “a very, very sad day,” Damri said, “so we expect the Arab friends to relate to our sadness and vice versa. When it’s Nakba day, I don’t personally feel sadness. I’m glad that there’s a state, and I think that most of the Israelis are happy on Independence Day. But… I want to offer sympathy to their pain, because they’re my friends. Of course we need to sit and talk and understand and solve the problem — but we’re not about solving the Israeli-Palestine conflict. We don’t have the power to do that.”

(Students at Hagar are not allowed to commemorate the Nakba, a day of mourning for Palestinians displaced in 1948, because of a 2011 Israeli law prohibiting public institutions from doing so.)

Of course, times like these, when Beersheba is under constant threat of rocket attacks from Gaza, are particularly trying. Last year, after a rocket landed perilously close to the school, an American donor provided the funding to transform Hagar’s bomb shelter into a ship-themed library. “I think that the story of the library ship is the story of Hagar,” Damri said. “We know that we have to use the bomb shelter, but let’s do it [so it is] less traumatic. Let’s create something together, so we feel that this is our haven.”

Political situation aside, for many instructors, co-teaching in a bilingual setting poses its own challenges. “It’s not difficult, it’s just different,” Arab fifth-grade teacher Sakena Ghara said. “It’s different from any framework I’ve been used to previously, and it needs a lot of creativity, originality and qualifications to implement it.”

But the school’s teachers express fierce loyalty to the program. “This place is so special, and I never thought I could connect with a place like this,” Jewish kindergarten teacher Lital Hermon-Elbaz said. “I was a fighter in the army at the checkpoints, and [Hagar] was the place where I got work. Now I’ve been headhunted from other schools, and I said, ‘No, I love this place.’ My best friend now is Arab.”

As the school grows, it will undoubtedly face countless hurdles. Next year, the school will add a sixth-grade level and begin teaching those students history, a topic fraught with conflict and multiple narratives. And when Hagar adds a high school, it will no doubt have to contend with touchy issues like dating between Arabs and Jews, and how to prepare the Jewish students, but not their Arab peers, for army service.

“These are all issues that we haven’t addressed yet, because we’re young and we’re not there yet,” development director Keren Simons said. “We’ve never said this is all going to be fun. We commit to respect and also to discuss and to figure out stuff together…. And also to give the kids credit, because the kids believe in what school they’re in. They’re not oblivious to what’s happening; they’re very knowledgeable, and they’re being taught how to be analytical…. I have faith that it’s going to work out well.”

Katherine Martinelli is a freelance food and travel writer in Beersheba, Israel.